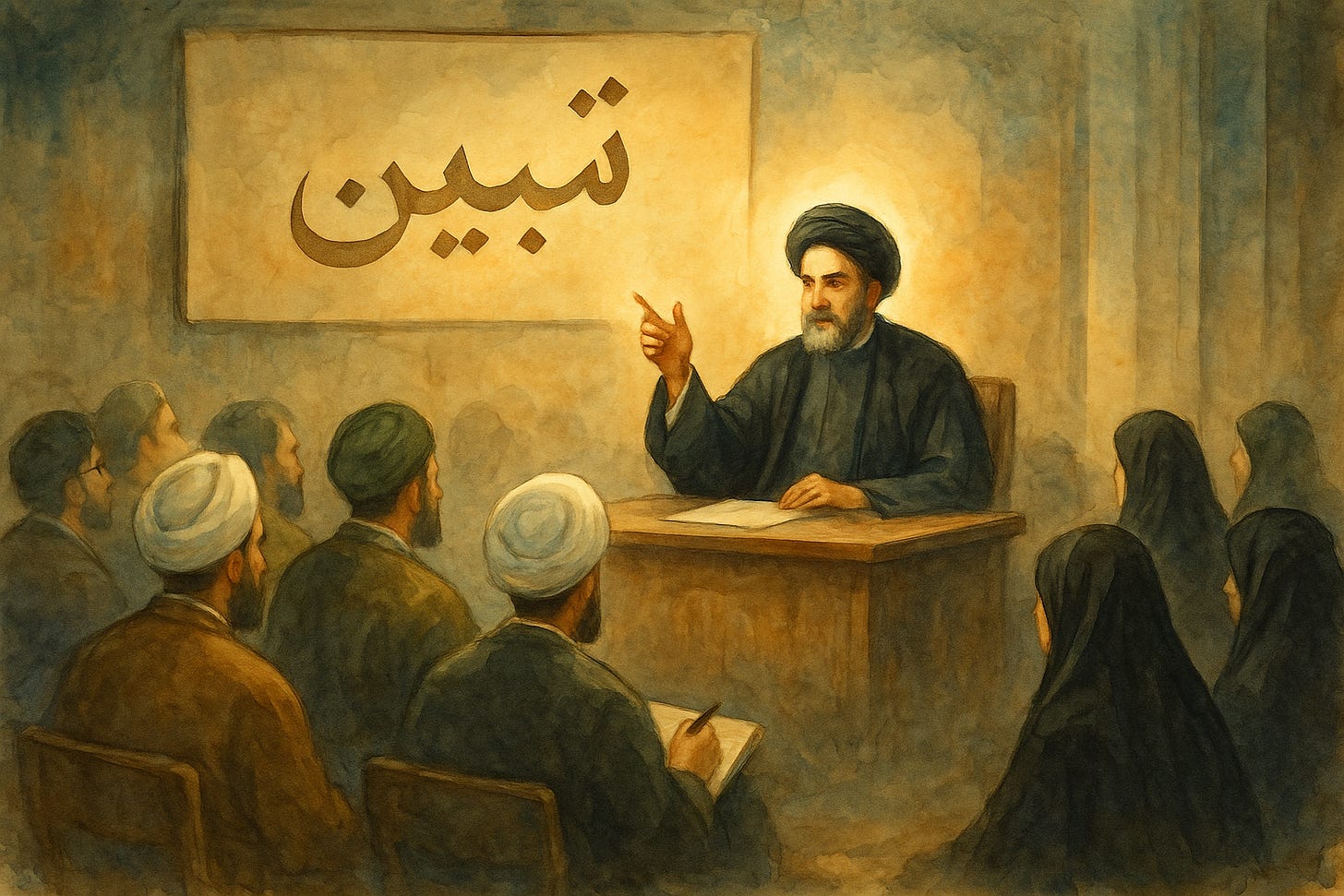

[11] Tabyeen (Clarification) - The Trust and the Pulpit

A series of discussions on the notion of tabyeen; critical within Islam and Islamic thought. This series is based on lectures delivered by Imam Khamenei. These sessions are for Arbaeen 2025/1447

In His Name, the Most High

اَلسَّلَامُ عَلَيْكَ يَا بْنَ رَسُولِ اللَّهِ

اَلسَّلَامُ عَلَيْكَ يَا بْنَ سَيِّدِ الْأَوْصِيَاءِ

نَشْهَدُ أَنَّكَ أَمِينُ اللَّهِ وَابْنُ أَمِينِهِ

عِشْتَ سَعِيداً وَمَضَيْتَ حَمِيداً وَمُتَّ فَقِيداً مَظْلُوماً شَهِيداً

وَنَشْهَدُ أَنَّ اللَّهَ مُنْجِزٌ مَا وَعَدَكَ

وَمُهْلِكٌ مَنْ خَذَلَكَ وَمُعَذِّبٌ مَنْ قَتَلَكَ

وَنَشْهَدُ أَنَّكَ وَفَيْتَ بِعَهْدِ اللَّهِ

وَجَاهَدْتَ فِي سَبِيلِهِ حَتَّى أَتَاكَ الْيَقِينُ

فَلَعَنَ اللَّهُ مَنْ قَتَلَكَ وَظَلَمَكَ

وَلَعَنَ اللَّهُ أُمَّةً سَمِعَتْ بِذَلِكَ فَرَضِيَتْ بِهِ

اللَّهُمَّ إِنَّا نُشْهِدُكَ أَنَّا أَوْلِيَاءُ لِمَنْ وَلاَكَ

وَأَعْدَاءُ لِمَنْ عَادَاكَ

بِآبَائِنَا وَأُمَّهَاتِنَا يَا بْنَ رَسُولِ اللَّهِPeace be upon you, O son of the Messenger of God.

Peace be upon you, O son of the Master of the Successors.We bear witness that you are the trustee of God and the son of His trustee.

You lived a blessed life, departed praiseworthy, and died a martyr, deprived and wronged.

And we bear witness that God will fulfil what He promised you,

and will destroy those who abandoned you, and punish those who killed you.

And we bear witness that you fulfilled the covenant of God,

and strove in His way until certainty came to you.So may God’s mercy be away from those who killed you and wronged you,

and may God’s mercy be away from the people that heard of this and was pleased with it.O God, we make You our witness that we are friends to those who befriend you,

and enemies to those who are hostile to you.

May our fathers and mothers be sacrificed for you, O son of the Messenger of God.— Adapted from Ziyarat Arbaeen1

Introduction

This is the eleventh in our series of sessions, for the nights of Ashura and now continuing in these blessed nights of Arbaeen, on the subject of Tabyeen (or clarification).

This is the first part of the second series on Tabyeen, we will be continuing this series during the remaining five nights of Arbaeen, God willing.

As with our other sessions - such as those on Patience, the Lantern of the Path or on the Art of Supplication - it is strongly recommended that the reader, at the very least review the previous sessions prior to consuming this one.

This is because of the nature of the discussion, and the manner of discourse requires that each part build upon the ones that came before; so as to avoid confusion, misunderstanding and any invalid assumptions; that can lead to what would be the antithesis of tabyeen (clarification).

While we do have a recap for each session, the recap is highly summarised, and to get the full nuance, the previous sessions will need to be consumed, studied and reflected upon.

The previous sessions can be found here:

Video of the Majlis (Sermon/Lecture)

Audio of the Majlis (Sermon/Lecture)

Recap

What we Learned in the First Ten Sessions

In the first ten sessions of this series, we embarked on a journey through the theology, urgency, and responsibility of tabyeen — clarification — not as a rhetorical exercise, but as a sacred covenant. A divine obligation upon every believer, and an even weightier duty upon those who possess influence, knowledge, and voice.

We began by uncovering the meaning of tabyeen in the Quranic sense — a process not merely of speaking, but of unveiling; not just of informing, but of exposing falsehood, restoring meaning, and guiding the community toward divine truth.

وَإِذْ أَخَذَ ٱللَّهُ مِيثَـٰقَ ٱلَّذِينَ أُوتُوا۟ ٱلْكِتَـٰبَ لَتُبَيِّنُنَّهُۥ لِلنَّاسِ وَلَا تَكْتُمُونَهُ

“And when God took a covenant from those who were given the Book: You shall certainly clarify it for the people and not conceal it.”

— Quran, Surah Aal-i-Imraan (The Chapter of the Family of Imraan) #3, Verse 187

We then explored the benefits and effects of tabyeen (clarification) — how it fortifies faith, guards the ummah (community) from manipulation, and strengthens the moral conscience of a society. We studied the requirements of clarification — spiritual sincerity (ikhlas), courage, firm alignment with divine leadership (wilayah), and intellectual integrity — all as prerequisites for valid clarification.

From there, we turned to the subjects in need of clarification: truth and falsehood, justice and injustice, unity and hypocrisy, divine leadership and worldly tyranny. We reflected on the methods and styles of tabyeen — from speech and action, to protest and patience — and how each has its place, depending on the moment and the mission.

Throughout, we walked with the exemplars of clarification: the Prophets (peace be upon them), Imam Ali (peace be upon him), Ammar ibn Yasir, Sayyedah Zaynab, Imam al-Sajjad (peace be upon them), and the martyrs and thinkers of modern Islamic resistance — those who bore the weight of clarification even when it cost them everything.

But we also warned of the illusions of tabyeen — when speakers talk endlessly but say nothing; when words are used to pacify rather than awaken; when so-called clarification becomes an instrument of concealment. We concluded with a deeper danger: deviation after guidance.

In the final session, we asked: What happens after the truth is clarified?

We spoke of those who recognise the truth and even side with it, only to fall away later — not out of ignorance, but due to fear, fatigue, love of comfort, or worldly entanglement.

The Quran teaches us:

وَمَا يُؤْمِنُ أَكْثَرُهُم بِٱللَّهِ إِلَّا وَهُم مُّشْرِكُونَ

“And most of them do not believe in God without also associating others with Him.”

— Quran, Surah Yusuf (The Chapter of (Prophet) Joseph) #12, Verse 106

and in Nahjul Balagha, Imam Ali teaches us:

كَمْ مِنْ عَقْلٍ أَسِيرٍ تَحْتَ سُلْطَانِ الْهَوَى

“How many an intellect is imprisoned under the dominion of desire.”

—Nahj al-Balagha2, Hikmah #222

Even the sincere can falter. And so, the Quran offers a piercing warning:

قُلْ هَلْ نُنَبِّئُكُم بِالْأَخْسَرِينَ أَعْمَالًا

الَّذِينَ ضَلَّ سَعْيُهُمْ فِي الْحَيَاةِ الدُّنْيَا وَهُمْ يَحْسَبُونَ أَنَّهُمْ يُحْسِنُونَ صُنْعًا

أُولَٰئِكَ الَّذِينَ كَفَرُوا بِآيَاتِ رَبِّهِمْ وَلِقَائِهِ فَحَبِطَتْ أَعْمَالُهُمْ فَلَا نُقِيمُ لَهُمْ يَوْمَ الْقِيَامَةِ وَزْنًا“Say, shall We inform you who the greatest losers in regard to deeds are? Those whose efforts are misguided in the life of the world, while they suppose they are doing good.

It is they who defy the signs of their Lord and the meeting with Him.

So their works are in vain, and We shall assign no weight to them on the Day of Resurrection.”— Quran, Surah al-Kahf (The Chapter of the Cave) #18, Verses 103–105

These are those who lost everything — not because they lacked effort, but because they lacked alignment. They concealed what should have been clarified.

They feared the creation more than the Creator.

And so, having walked the terrain of tabyeen in its principles, methods, dangers, and exemplars — we now step into the next phase of this journey.

In these five sessions prepared for the days of Arbaeen, we turn our gaze to the agents of tabyeen — the people upon whom this trust rests. Those who speak from the pulpit. Those who teach in our seminaries and schools. Those who lead the youth, guide women, write poetry, produce culture, and carry public voice.

The trust of clarification is not held by one class — it is the duty of all who have reach.

And so, we begin this next phase… with the pulpit.

Tabyeen (Clarification) - The Trust and the Pulpit

There are few responsibilities in Islam more sacred than that of the minbar — the pulpit from which God’s message is conveyed to His creation. To speak from the minbar is not merely to raise one’s voice — it is to carry an amanah (trust), to deliver a message rooted in revelation, and to step into the legacy of the Prophets and Imams.

Literal Platform, Symbolic Responsibility

Lexically, minbar comes from the root ن-ب-ر, meaning “to rise” or “to stand elevated.” Originally, it referred to the physical structure the Prophet Muhammad (peace and blessings be upon him and his family) used in the mosque of Madinah to address the ummah.

However, from the earliest days, classical Shia scholars understood the minbar as both concrete and metonymic: it referred not just to a platform, but to any locus of sacred instruction and moral authority — from a circle of teaching (halaqah), to a conference panel, to a satellite broadcast, a YouTube channel, or a social media page.

Allamah Majlisi writes:

“المراد بالمنبر، كل مقام للتعليم والإرشاد، لا يختص بالخشبة في المسجد.”

“What is meant by the pulpit is every station of teaching and guidance; it is not limited to the wooden platform in a mosque.”

Therefore, the Quranic and hadeeth-based responsibilities tied to the minbar apply not just to the physical elevation of the speaker, but to the moral height of what is being conveyed.

The Prophetic Trust and Its Betrayal

To ascend the pulpit is to inherit a divine trust. And to betray it, is among the gravest of sins.

The Prophet Muhammad (peace and blessings be upon him and his family) warned:

يَأْتِي عَلَى النَّاسِ زَمَانٌ لَا يَبْقَى مِنَ الْإِسْلَامِ إِلَّا اسْمُهُ، وَلَا مِنَ الْقُرْآنِ إِلَّا رَسْمُهُ، مَسَاجِدُهُمْ عَامِرَةٌ وَهِيَ خَرَابٌ مِنَ الْهُدَى، فُقَهَاءُ ذَلِكَ الزَّمَانِ شَرُّ فُقَهَاءَ تَحْتَ ظِلِّ السَّمَاءِ، مِنْهُمْ خَرَجَتِ الْفِتْنَةُ وَإِلَيْهِمْ تَعُودُ

“A time will come when nothing will remain of Islam but its name, and nothing of the Quran but its script.

Their mosques will be full of worshippers, but devoid of guidance. The jurists of that time will be the worst jurists under the sky — from them tribulation will emerge, and to them it will return.”

— Al-Ameli5, Wasail al-Shia6, Section 11, Hadeeth 28 (Volume 27, Page 34)

— Al-Majlisi7, Bihar al-Anwar8, Volume 52, Page 190

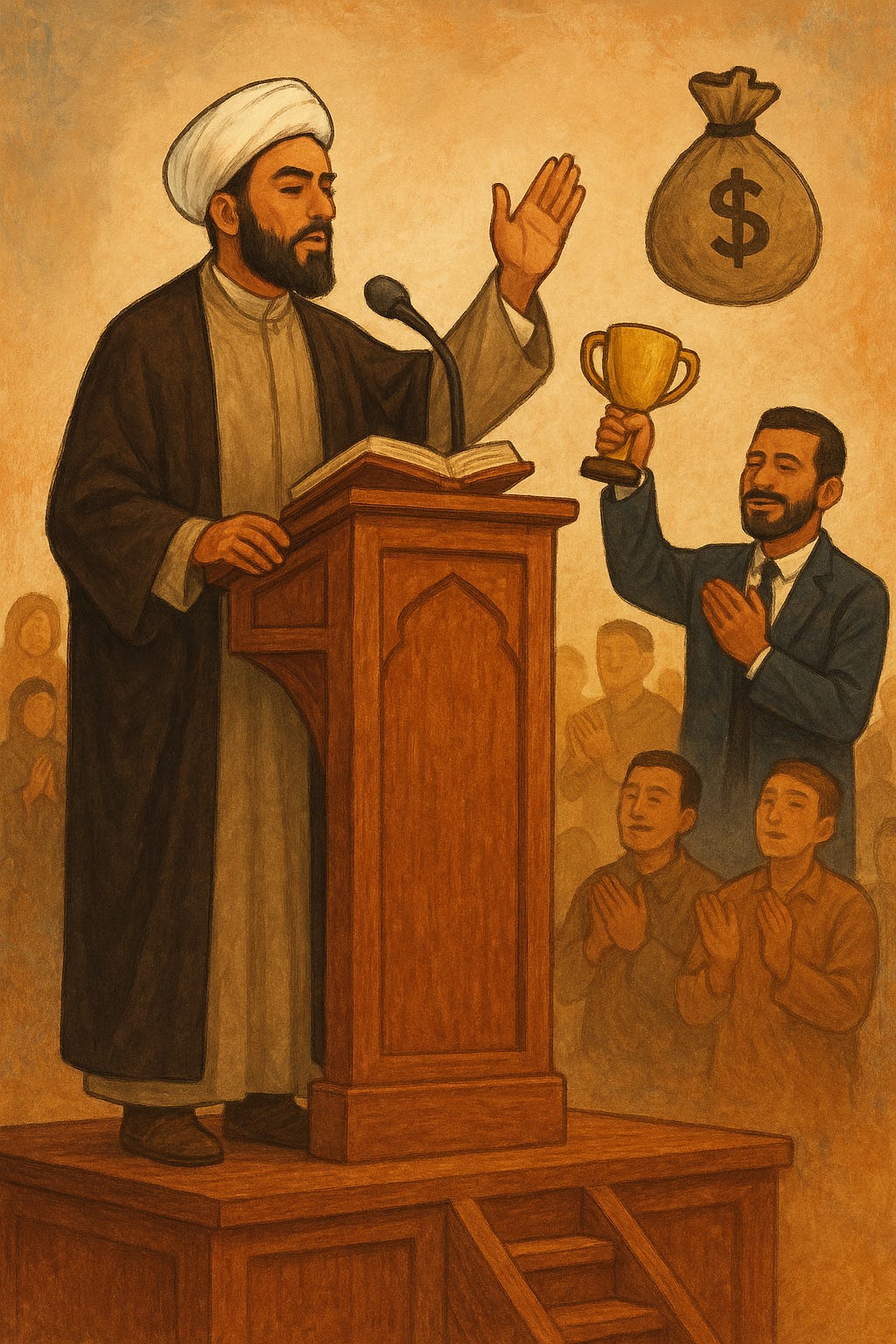

The minbar becomes a minbar al-su (the evil pulpit) when it is occupied by such figures — when the speaker’s goal is not truth, but self-promotion, status, or monetary gain.

Imam al-Sadiq (peace be upon him) warned:

إِذَا رَأَيْتَ الْعَالِمَ مُحِبًّا لِدُنْيَاهُ فَاتَّهِمْهُ عَلَى دِينِكَ، فَإِنَّ كُلَّ مُحِبٍّ لِشَيْءٍ يَحُوطُ مَا أَحَبَّ

“When you see a scholar who loves the world, hold your religion in suspicion with him — for whoever loves something protects it above all else.”

And again:

شَرُّ الْعُلَمَاءِ مَنْ يَزُورُ الْأُمَرَاءَ، وَخَيْرُ الْأُمَرَاءِ مَنْ يَزُورُ الْعُلَمَاءَ

“The worst of scholars are those who visit the doors of rulers; and the best of rulers are those who visit the doors of scholars.”

Imam Ali (peace be upon him) described the decay of the pulpit in these terms:

قَدْ ظَهَرَ فِسْقُ الْخُطَبَاءِ، وَكُوفِئَتِ الْأَمَانَةُ بِالْخِيَانَةِ، وَصَارَ السُّلْطَانُ بِالشُّبْهَةِ، وَعُلُوُّ الْمِنْبَرِ لِمَنْ لَا يَسْتَحِقُّهُ

“The immorality of preachers has become manifest; trust is answered with treachery; authority is gained by dubious means; and the pulpit is ascended by one who does not deserve it.”

— Nahjul Balagha (Faysal Edition)13, Sermon 97

These are not abstract warnings. They define the conditions by which a platform — any platform — becomes spiritually bankrupt. The classical scholars explain that a platform becomes a condemned pulpit (minbar al-su) when three core traits converge:

The Platform is Used for Worldly Gain

The first indicator is when the scholar or speaker studies or teaches religion not for the sake of God, but for status, applause, income, or institutional favour.

Prophet Muhammad has warned:

سَيَأْتِي زَمَانٌ عَلَى أُمَّتِي يَكْثُرُ فِيهِ الْقُرَّاءُ وَيَقِلُّ الْفُقَهَاءُ، وَيَقْبِضُ الْعِلْمُ، وَيَكْثُرُ الْهَرَجُ… يَتَفَقَّهُونَ لِغَيْرِ الدِّينِ، وَيَطْلُبُونَ الدُّنْيَا بِعَمَلِ الْآخِرَةِ

“A time will come upon my nation when reciters will be many and true jurists few; knowledge will be taken away, and chaos will increase… They will study religion for other than religion, and they will seek the world through acts of the Hereafter.”

This is not a critique of learning — it is a warning against the intention behind that learning.

When sacred knowledge becomes a means for profane ambition, the pulpit becomes polluted.

The Platform is Used to Mislead the People

The second condition arises when a person uses their religious authority to sow confusion, promote ideological deviation, or manipulate the emotions of the congregation for personal or political ends.

يَأْتِي عَلَى النَّاسِ زَمَانٌ لَا يَبْقَى مِنَ الْإِسْلَامِ إِلَّا اسْمُهُ، وَلَا مِنَ الْقُرْآنِ إِلَّا رَسْمُهُ، مَسَاجِدُهُمْ عَامِرَةٌ وَهِيَ خَرَابٌ مِنَ الْهُدَى، فُقَهَاءُ ذَلِكَ الزَّمَانِ شَرُّ فُقَهَاءَ تَحْتَ ظِلِّ السَّمَاءِ، مِنْهُمْ خَرَجَتِ الْفِتْنَةُ وَإِلَيْهِمْ تَعُودُ

“A time will come when nothing will remain of Islam but its name, and nothing of the Quran but its script. Their mosques will be full of worshippers, but devoid of guidance. The jurists of that time will be the worst jurists under the sky — from them tribulation will emerge, and to them it will return.”

— Al-Ameli16, Wasail al-Shia17, Section 11, Hadeeth 28 (Volume 27, Page 34)

— Al-Majlisi18, Bihar al-Anwar19, Volume 52, Page 190

This chilling description captures the spectacle of religious form without substance — external religiosity masking inner decay.

It is a diagnosis of spiritual corruption that emerges precisely when those in positions of religious authority abandon sincerity and surrender to factionalism or control.

The Platform is Claimed Without Moral Worth

The final condition is when a person assumes the role of a guide without having earned the spiritual and ethical right to do so.

They may possess credentials, eloquence, or popularity — but lack inner sincerity, God-consciousness, or qualification.

Imam Ali (peace be upon him) said in Nahjul Balagha:

قَدْ ظَهَرَ فِسْقُ الْخُطَبَاءِ، وَكُوفِئَتِ الْأَمَانَةُ بِالْخِيَانَةِ، وَصَارَ السُّلْطَانُ بِالشُّبْهَةِ، وَعُلُوُّ الْمِنْبَرِ لِمَنْ لَا يَسْتَحِقُّهُ

“The immorality of preachers has become manifest; trust is answered with treachery; authority is gained by dubious means; and the pulpit is ascended by one who does not deserve it.”

— Nahjul Balagha (Faysal Edition)20, Sermon 97

It is not elevation in height that matters, but elevation in truthfulness, knowledge, and humility. When someone takes the pulpit who has not been inwardly prepared to carry that weight, the minbar becomes a place of danger — not just to the speaker, but to all who listen and trust.

Thus, the issue is not where one sits, but what one serves.

A person may speak seated on the ground, but if their purpose is sincerity and truth, they have ascended the true minbar in God’s sight. And another may tower above the people, robed and spotlighted, but if they distort religion for worldly aims, they are no better than a corrupt merchant in a market.

تُعِزُّ مَن تَشَاءُ وَتُذِلُّ مَن تَشَاءُ

“You honour whom You will, and You abase whom You will.”

— Quran, Surah Aal-i-Imran (the Chapter of the Family of Imraan) #3, Verse 26

The minbar is a trust — and honour belongs only to those who fulfil it.

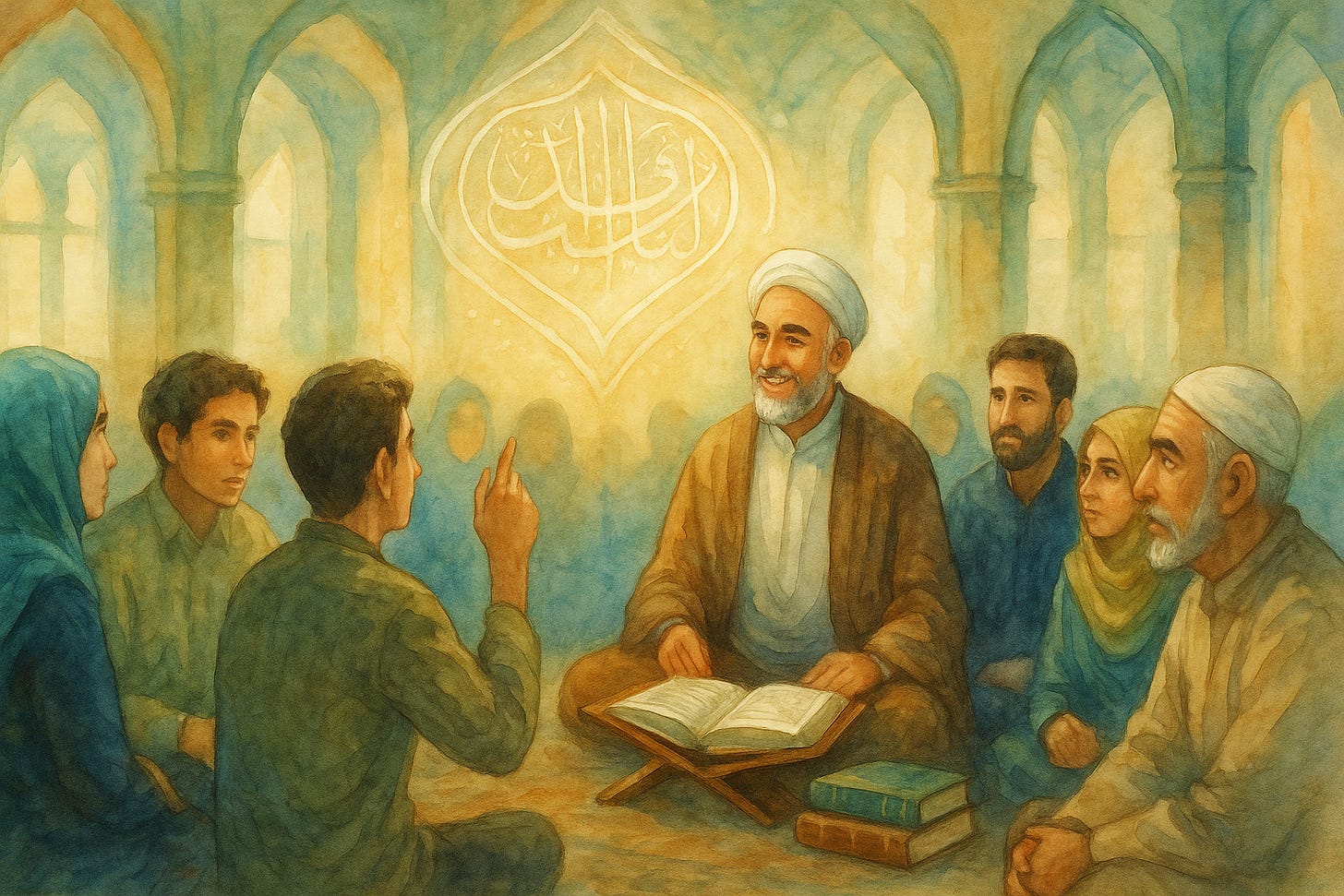

Speaking to the People at Their Level: The Duty of Educative Communication

One of the distinguishing features of the Prophet’s mission — and of every rightful scholar who inherits from him — is the deep concern for how to communicate. Not just what to say, but how, when, and to whom.

The goal is not intellectual display, but spiritual elevation.

The Prophet Muhammad (peace and blessings be upon him and his family) tailored his speech to his audience. He did not speak above their heads, nor did he pander to their desires. He was, in every sense, a teacher — a physician of the soul.

Imam Ali (peace be upon him) described him as one who carried his healing remedies wherever he went, always attentive to those whose souls were in pain.

In our tradition, both Quran and hadeeth stress the importance of speaking to people according to their level of understanding.

إِنَّا كُنَّا نُرْسِلُ الرُّسُلَ إِلَّا بِاللِّسَانِ قَوْمِهِ لِيُبَيِّنَ لَهُمْ

“We do not send any apostle except with the language of his people so that he may make things clear to them.”

— Quran, Surah Ibrahim (the Chapter of Abraham) #14, Verse 4

Likewise, we find in al-Kafi from Imam al-Sadiq (peace be upon him):

قُولُوا لِلنَّاسِ أَحْسَنَ مَا تُحِبُّونَ أَنْ يُقَالَ لَكُمْ، فَإِنَّ اللَّهَ يُبْغِضُ اللَّاعِنَ السَّبَّابَ الطَّعَّانَ عَلَى الْمُؤْمِنِينَ، الْعَائِبَ عَلَيْهِمْ

“Speak to people in the best way you would love to be spoken to. Surely, God detests the one who curses, insults, and finds fault with the believers.”

And in another narration:

إِنَّمَا النَّاسُ كَالنَّاسِ مِنَ الْجِبَالِ فِيهِمُ الْأَشْرَافُ وَالْأَنْذَالُ

“Indeed, people are like minerals in the mountains; among them are the noble and the base.”

The speaker must, therefore, be discerning — identifying who in the crowd is seeking truth, who is confused, who is arrogant, and who is ready to grow.

As Imam al-Sadiq (peace be upon him) also said:

حَدِّثُوا النَّاسَ بِمَا يَعْرِفُونَ وَدَعُوا مَا يُنْكِرُونَ

“Speak to the people with what they know, and leave what they reject.”

This is not a call to conceal the truth — far from it. It is a call to gradualism, to wisdom, to knowing how to feed each soul with what it can digest.

The pulpit is not a place to dump complex technicalities upon an unprepared audience, nor to use jargon and citation as a tool of intimidation.

The Role of Questions in True Learning

An intelligent, God-fearing speaker welcomes questions. He is not threatened by them. He knows that the pulpit is not a monologue, but a trust that includes dialogue — if not during the speech, then certainly afterward.

The Quran constantly uses rhetorical questions as a method of stirring thought.

The Prophet (peace and blessings be upon him and his family) never mocked a sincere questioner. Rather, he praised them and often answered with gentleness and insight.

The Prophet said - from Sunni sources:

طَلَبُ الْعِلْمِ فَرِيضَةٌ عَلَى كُلِّ مُسْلِمٍ

“Seeking knowledge is an obligation upon every Muslim.”

and from Shia Sources, Imam as-Sadiq quotes the Prophet:

عَنْ أَبِي عَبْدِ اللَّهِ (عَلَيْهِ السَّلَامُ) قَالَ: قَالَ رَسُولُ اللَّهِ (صَلَّى اللَّهُ عَلَيْهِ وَآلِهِ): طَلَبُ الْعِلْمِ فَرِيضَةٌ عَلَى كُلِّ مُسْلِمٍ. أَلَا وَإِنَّ اللَّهَ يُحِبُّ بُغَاةَ الْعِلْمِ

From Abu Abdillah (Imam Ja'far al-Sadiq) (peace be upon him), he said: The Messenger of God (peace be upon him and his family) said: “Seeking knowledge is an obligation upon every Muslim. Indeed, God loves those who seek knowledge.”

— Al-Kulayni29, Al-Kafi30, Vol. 1, Book of the Virtue of Knowledge, Chapter 1, Hadeeth 1

And in a narration attributed to Imam al-Baqir (peace be upon him):

زَكَاةُ الْعِلْمِ نَشْرُهُ، وَتَعْلِيمُهُ لِمَنْ لَا يَعْلَمُهُ

“The zakat (alms, charity, religious tax) of knowledge is to spread it and to teach it to those who do not know.”

Therefore, if a congregant does not understand something said from the pulpit, they have not only the right, but in many cases the duty, to ask for clarification — respectfully and with humility.

If the speaker refuses to clarify, mocks the question, or allows others to mock the questioner, they betray their trust.

Such a speaker is not a teacher — they are a fraud in a robe.

Imam al-Sadiq (peace be upon him) cautioned:

إِيَّاكُمْ وَالتَّقَلُّدَ، فَإِنَّهُ لَا دِينَ لِمَنْ تَقَلَّدَ دِينَهُ

“Beware of blind imitation, for there is no religion in one who imitates blindly in religion.”

So the duty of the speaker is not only to deliver knowledge, but to foster a climate in which questions are welcomed, humility is modelled, and learning is mutual.

The responsibility is enormous — and the consequences of betrayal, severe.

The Quran reminds:

وَلَا تَقْفُ مَا لَيْسَ لَكَ بِهِ عِلْمٌ ۚ إِنَّ السَّمْعَ وَالْبَصَرَ وَالْفُؤَادَ كُلُّ أُولَٰئِكَ كَانَ عَنْهُ مَسْئُولًا

“Do not pursue that of which you have no knowledge. Indeed, the hearing, the sight and the heart — all of them will be questioned.”

— Quran, Surah al-Isra (the Chapter of the Night Journey) #17, Verse 36

When the Pulpit Becomes a Stage: The Crisis of Self-Glorification and Name-Dropping

The pulpit (minbar) was never meant to be a stage. It was never intended as a platform for theatrical delivery, self-promotion, or artificial displays of piety.

It was, and remains, a station of humility — a perch of trust passed down from the Prophet Muhammad (peace and blessings be upon him and his family) to those who seek to clarify God’s truth with sincerity and courage.

Yet, in too many instances, the minbar has been transformed into an arena for riya — ostentation — and even deception. This is especially evident in the growing phenomenon of name-dropping among some who wear the scholar’s garb.

We have witnessed individuals climbing the pulpit and claiming connection to revered figures they never met, reciting tales that collapse under scrutiny, and invoking names to evoke awe in the audience rather than to impart wisdom.

One such instance: a speaker boldly claimed to have been a student of Rajabali Khayyat — a renowned spiritual figure who passed away in 1961 — despite the speaker’s own birth occurring well after that date.

More disturbing than the falsehood itself, was the audience’s blind acceptance of it.

No one dared to challenge him.

Why?

Because we have elevated those who sit atop the pulpit to the status of untouchable authorities — infallible in appearance if not in doctrine.

We have projected upon the turbaned speaker a sanctity that is only due to the infallibles. And in doing so, we have allowed falsehood to pass unchallenged, and truth to be obscured by performance.

The words of Imam Ali (peace be upon him) strike to the heart of this issue:

انْظُرْ إِلَى مَا قَالَ وَلَا تَنْظُرْ إِلَى مَنْ قَالَ

“Look at what is said, not who said it.”

— Nahjul Balagha35, Saying 300

This is not a call for disrespect — it is a call for discernment. Truth is not validated by titles, robes, or honourifics. It is validated by evidence, reason, and alignment with the Quran and the teachings of the Ahl al-Bayt (peace be upon them).

Indeed, the Imams warned against the corrupting lure of public acclaim and institutional authority.

Imam al-Sadiq (peace be upon him) is reported to have said:

إِذَا رَأَيْتُمُ الْعَالِمَ يُحِبُّ الدُّنْيَا فَاتَّهِمُوهُ عَلَى دِينِهِ

“If you see a scholar who loves the world, then accuse him concerning his religion.”

And Imam Ali (peace be upon him) stated:

شَرُّ الْعُلَمَاءِ مَنْ أَحَبَّ الْمُلُوكَ، وَخَيْرُ الْمُلُوكِ مَنْ زَارَ الْعُلَمَاءَ

“The worst of scholars are those who love kings, and the best of kings are those who visit the scholars.”

The Quran, too, condemns those who distort religious knowledge for personal gain:

فَوَيْلٌ لِّلَّذِينَ يَكْتُبُونَ الْكِتَابَ بِأَيْدِيهِمْ ثُمَّ يَقُولُونَ هَٰذَا مِنْ عِندِ اللَّهِ لِيَشْتَرُوا بِهِ ثَمَنًا قَلِيلًا

“So woe to those who write the Book with their own hands and then say, ‘This is from God,’ in order to gain a small price thereby.”

— Quran, Surah al-Baqarah (the Chapter of the Cow) #2, Verse 79

Name-dropping, title-flaunting, and sanctimony — when done to manipulate, mislead, or dominate an audience — are not minor faults. They are betrayals of the sacred trust of the minbar. A speaker should be judged not by whom he studied with, but by what he delivers; not by the weight of names, but by the clarity of meaning.

The true scholar is not defined by anecdotes, nor by proximity to famous personalities, but by alignment with truth.

As the Quran commands:

وَكُونُوا مَعَ الصَّادِقِينَ

“And be with the truthful.”

— Quran, Surah al-Tawbah (the Chapter of Repentance) #9, Verse 119

The lesson is simple yet urgent: when the pulpit becomes a stage, religion becomes spectacle, and the people suffer.

Tabyeen, the sacred duty of clarification, demands that we strip away performance and falsehood, and return to sincerity, simplicity, and truth.

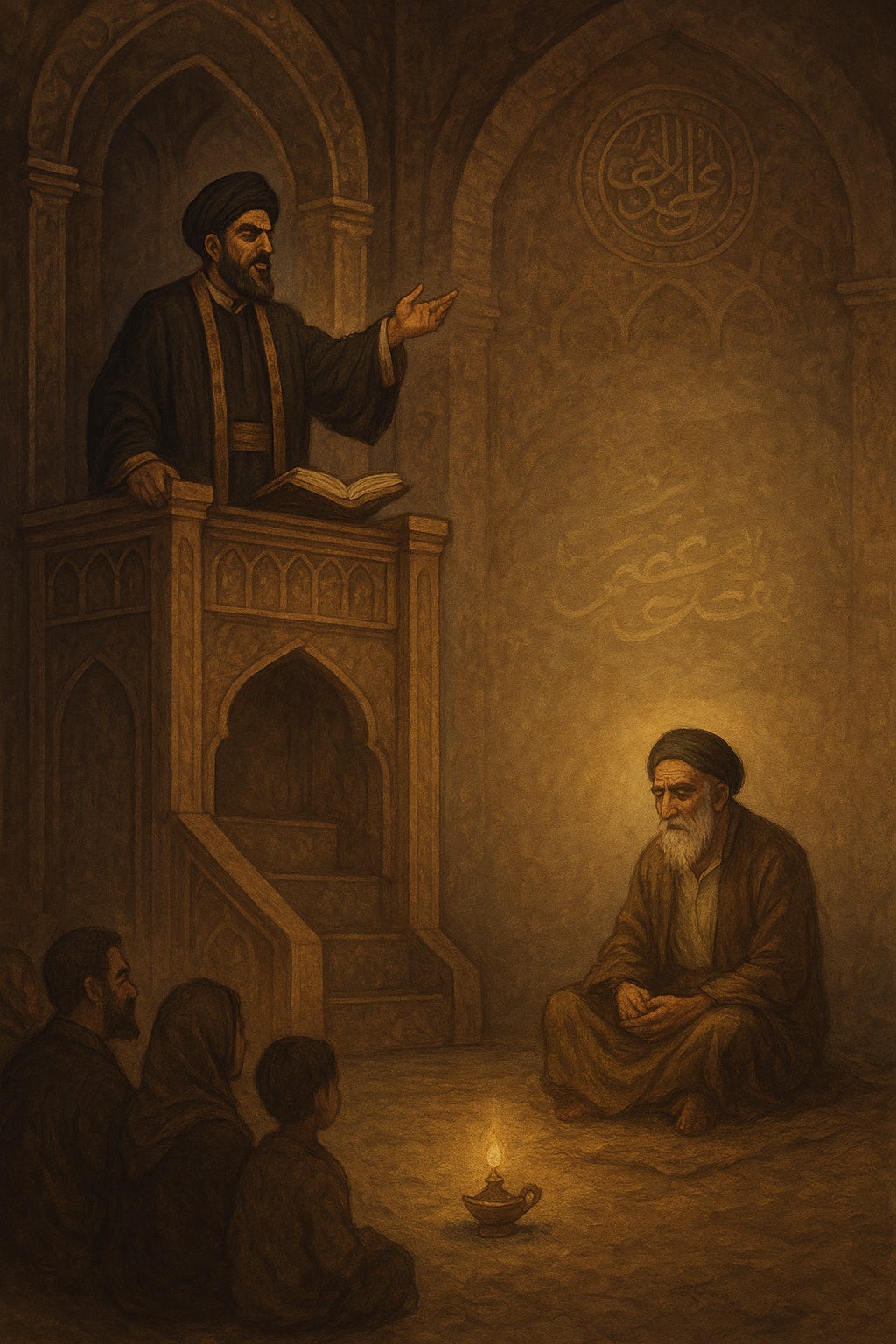

False Authority, Silent Scholars, and the Cost of Cowardice

In every generation, the truth is not only threatened by the tongues of the liars, but also by the silence of those who know better. The corruption of religion does not happen solely through fabrication — it happens equally through omission, hesitation, and cowardice. And perhaps nowhere is this betrayal more evident than upon the pulpit.

There are scholars and speakers who ascend the minbar but do not speak what is needed. They choose safety over sincerity, comfort over confrontation. Their speech becomes a reflection not of divine duty, but of the expectations of a governing board, the anxieties of a donor class, or the need to preserve their own image. They tiptoe around urgent truths. They avoid names, avoid issues, avoid responsibility — all in the name of “wisdom,” when in fact it is worldliness in disguise.

The Quran issues a sharp rebuke to such behaviour:

إِنَّ الَّذِينَ يَكْتُمُونَ مَا أَنزَلْنَا مِنَ الْبَيِّنَاتِ وَالْهُدَىٰ مِن بَعْدِ مَا بَيَّنَّاهُ لِلنَّاسِ فِي الْكِتَابِ أُولَٰئِكَ يَلْعَنُهُمُ اللَّهُ وَيَلْعَنُهُمُ اللَّاعِنُونَ

“Indeed, those who conceal what We sent down of clear proofs and guidance after We made it clear for the people in the Book — they are the ones whom God curses, and they are cursed by all who curse.”

— Quran, Surah al-Baqarah (the Chapter of the Cow) #2, Verse 159

What greater betrayal can there be than a scholar who knows the truth but refuses to speak it? What spiritual state must one be in to sit where the Prophet once sat, dress in the garb of his successors, and yet cower before worldly consequences?

The Quran continues in another verse:

وَلَا تَكْتُمُوا الشَّهَادَةَ ۚ وَمَن يَكْتُمْهَا فَإِنَّهُ آثِمٌ قَلْبُهُ

“Do not conceal testimony. Whoever conceals it, his heart is sinful.”

— Quran, Surah al-Baqarah (the Chapter of the Cow) #2, Verse 283

When the pulpit becomes a seat of fear — fear of losing funding, fear of offending the powerful, fear of being labelled “political” or “divisive” — then it is no longer a minbar, but a throne of cowardice.

And the one who occupies it, regardless of title, has fallen into a state of betrayal.

The Quran warns repeatedly:

فَخَسِرَ الدُّنْيَا وَالْآخِرَةَ ۚ ذَٰلِكَ هُوَ الْخُسْرَانُ الْمُبِينُ

“He loses this world and the hereafter — that is the manifest loss.”

— Quran, Surah al-Hajj (the Chapter of the Pilgrimage) #22, Verse 11

And again:

قُلْ هَلْ نُنَبِّئُكُم بِالْأَخْسَرِينَ أَعْمَالًا * الَّذِينَ ضَلَّ سَعْيُهُمْ فِي الْحَيَاةِ الدُّنْيَا وَهُمْ يَحْسَبُونَ أَنَّهُمْ يُحْسِنُونَ صُنْعًا

“Say, shall We inform you of the greatest losers in deeds? They are those whose effort is lost in this worldly life, while they think they are doing well.”

— Quran, Surah al-Kahf (the Chapter of the Cave) #18, Verses 103–104

The illusion of honour, the facade of scholarship — all of it will collapse. For honour comes only from God:

تُعِزُّ مَن تَشَاءُ وَتُذِلُّ مَن تَشَاءُ

“You honour whom You will, and You abase whom You will.”

— Quran, Surah Aal-i-Imraan (the Chapter of the Family of Imraan) #3, Verse 26

The Imam’s Standard for Truthful Speech

Imam al-Sadiq (peace be upon him) was once asked why some people conceal what they know to be true. He replied:

إِذَا سَمِعَ النَّاسُ شَيْئًا عَجِبُوا، وَقُلْنَا نَحْنُ نَتَكَلَّمُ عَلَى قَدْرِ عُقُولِهِمْ

“When people hear something strange, they are shocked. So we speak to them according to the level of their intellect.”

This is not a justification for silence. It is a blueprint for gradual but necessary disclosure. The Imams did not abandon their duty; they performed it wisely, without cowardice.

The Prophet (peace and blessings be upon him and his family) similarly declared - from Sunni sources:

مَنْ رَأَى مُنْكَرًا فَلْيُغَيِّرْهُ بِيَدِهِ، فَإِنْ لَمْ يَسْتَطِعْ فَبِلِسَانِهِ، فَإِنْ لَمْ يَسْتَطِعْ فَبِقَلْبِهِ، وَذَٰلِكَ أَضْعَفُ الْإِيمَانِ

“Whoever sees evil, let him change it with his hand. If he cannot, then with his tongue. And if he cannot, then with his heart — and that is the weakest of faith.”

And equivalents from Shia sources are:

عن أبي جعفر عليه السلام قال:

قال رسول الله صلى الله عليه وآله:

إنما هلكت الأمم التي كانت قبلكم حيث لم يكن يغير المنكر إلا من رأى منكرا فأنكره بيده ولسانه وقلبه، فاقتصروا على ذلك.From Abu Ja‘far (Imam al-Baqir) (peace be upon him), he said:

The Messenger of God (peace be upon him and his family) said:

“Verily, the nations before you perished only because when they saw evil, only those who saw it would denounce it with their hand, their tongue, and their heart, and they limited themselves to that.”— Al-Ameli44, Wasail al-Shia45, Volume 16, Page 140, Hadeeth 21207

and also from Imam Ali:

قال أمير المؤمنين عليه السلام:

أول ما تغلبون عليه من الجهاد: جهاد أيديكم، ثم جهاد ألسنتكم، ثم جهاد قلوبكم، فمن لم يعرف بقلبه معروفا ولم ينكر منكرا نكس فجعل أعلاه أسفله.Imam Ali (peace be upon him) said:

“The first thing you will lose from jihad is striving with your hands, then with your tongues, then with your hearts. Whoever does not recognise good with his heart and does not reject evil with his heart, will be turned upside down.”— Al-Majlisi46, Bihar al-Anwar47, Volume 97, Page 86

— Al-Saduq48, Al-Khisal49, Chapter of the Threes, Page 112, Hadeeth 109

Silence, in the face of corruption, is not hikmah (wisdom). It is khiyanah (betrayal). And betrayal of the message is a betrayal of the Messenger, and betrayal of the Messenger is betrayal of God, the one who sent the messenger.

Quran and the ahadeeth provide testimony to the gravity of this:

مَّن يُطِعِ الرَّسُولَ فَقَدْ أَطَاعَ اللَّهَ

Whoever obeys the Messenger has obeyed God…

— Quran, Surah al-Nisa (the Chapter of the Women) #4, Verse 80

and

وَمَا آتَاكُمُ الرَّسُولُ فَخُذُوهُ وَمَا نَهَاكُمْ عَنْهُ فَانتَهُوا

Whatever the Messenger gives you, take it; and whatever he forbids you, abstain from it…

— Quran, Surah al-Hashr (the Chapter of the Gathering) #59, Verse 7

And from the books of the Sunnah, the same lesson can be garnered:

مَنْ أَطَاعَنِي فَقَدْ أَطَاعَ اللَّهَ، وَمَنْ عَصَانِي فَقَدْ عَصَى اللَّهَ

Whoever obeys me has obeyed God, and whoever disobeys me has disobeyed God.

And also from the Shia sources, Imam as-Sadiq teaches us:

مَنْ أَطَاعَ مُحَمَّداً فَقَدْ أَطَاعَ اللَّهَ، وَمَنْ عَصَى مُحَمَّداً فَقَدْ عَصَى اللَّهَ

Whoever obeys Muhammad has obeyed God, and whoever disobeys Muhammad has disobeyed God.

And the same applies for those who disobeys the Imams, here, Imam al-Baqir teaches:

يَا جَابِرُ، مَنْ أَطَاعَنَا فَقَدْ أَطَاعَ اللَّهَ، وَمَنْ عَصَانَا فَقَدْ عَصَى اللَّهَ

O Jabir, whoever obeys us has obeyed God, and whoever disobeys us has disobeyed God.

Clarifying with Wisdom: The Methodology of Imam Khamenei and the Duty to Confront Misguidance

The pulpit is not immune from misguidance. On the contrary, it can become one of its most potent channels when wielded by the ignorant, the arrogant, or the compromised.

A speaker dressed in the garb of scholarship — yet divorced from sincerity, spiritual insight, or accountability — becomes an instrument of confusion rather than clarification.

In such cases, the response cannot be silence.

It must be tabyeen — clarification.

But this must be done wisely, patiently, and without compromising the unity of the community. Here, the teachings and example of Imam Khamenei are particularly instructive.

His articulation of Jihad al-Tabyeen — the struggle of clarification — is not merely reactive, but deeply strategic. It does not involve personal attacks or reckless confrontation.

Rather, it seeks to dismantle falsehood through wisdom, establish the truth with proofs, and empower the people with understanding.

Responding to Misleading Speech: A Case Study

Imagine a speaker who ascends the pulpit and declares that mourning rituals for Imam Husayn (peace be upon him) — such as latmiyyah (lamentations), or azadari (gatherings for the mourning of Imam Husayn and Ahl al-Bayt) — are a bidah (innovation), and should be discouraged or abandoned.

Such a statement, if left unchallenged, can unsettle hearts, fragment communities, and dilute the identity of the followers of the Ahl al-Bayt.

The method of tabyeen (clarification), as exemplified by Imam Khamenei, would involve:

Historical Clarification

Present the deep historical roots of these rituals within Shia tradition, citing their presence in the lives of the Imams and early scholars. Mention how Imam al-Sadiq and Imam al-Ridha (peace be upon them) encouraged poetry and mourning in remembrance of Karbala.

قَالَ الْإِمَامُ الرِّضَا (ع): مَنْ جَلَسَ مَجْلِسًا يُحْيَا فِيهِ أَمْرُنَا لَمْ يَمُتْ قَلْبُهُ يَوْمَ تَمُوتُ الْقُلُوبُ

“Whoever sits in a gathering in which our affair is revived, his heart shall not die on the Day when hearts die.”

Jurisprudential Evidence

Clarify that prominent jurists — past and present — including contemporary Maraji, such as Ayatullah Sistani, as well as the Wali al-Faqih, Imam Khamenei, regard such rituals as mustahabb (recommended), deeply rooted in Quranic principles of remembrance, loyalty, and love for the righteous, and love for those who love God, and whom God loves.

As an example; the ruling of Imam Khamenei in this regard is as follows:

إقامة مجالس العزاء على سيد الشهداء عليه السلام وإحياء ذكرى عاشوراء من أفضل القربات وأعظم العبادات، وهي جائزة بل مستحبة، ما لم تتضمن محرماً

Commemorating the martyrdom of Imam Husayn and holding mourning ceremonies for him is among the greatest acts of worship and the best means of drawing closer to God. It is not only permissible, but highly recommended, provided that it does not involve any forbidden acts.

— Imam Khamenei58

And the position of Ayatullah Sistani:

السؤال: هل الشعائر الحسينية (عزاء الإمام الحسين عليه السلام) مستحبة؟

الجواب: نعم، إنها مستحبة ولها ثواب جزيل، والله يثيب من يحيي ذكرهم ويقيم عزاءهم

Question: Are the Hussaini rituals (mourning for Imam Husayn, peace be upon him) recommended (mustahabb)?

Answer: Yes, they are recommended and have great reward, and God rewards whoever revives their memory and establishes their mourning.

— Ayatullah Sistani59

Spiritual Framing

Explain the transformative impact of these rituals: how they cultivate grief for oppression, strengthen identity, and renew allegiance to divine justice. For example, explain how, in Ziyarat Nahiya al-Muqaddasah60, we read that Imam Mahdi himself cries tears of blood, mourning for Imam Husayn:

لَأَنْدُبَنَّكَ صَبَاحاً وَ مَسَاءً، وَ لَأَبْكِيَنَّ عَلَيْكَ بَدَلَ الدُّمُوعِ دَماً

I will surely lament you morning and evening, and I will surely weep for you instead of tears, blood.

— Ziyarat Nahiyah al-Muqaddasah61

Also, quoting from Ziyarat Ashura or Dua al-Nudbah can easily illustrate this point.

Exposure of Underlying Agendas

If necessary, expose — gently — the ideological roots of such claims, particularly if they stem from external agendas seeking to dilute Islamic Unity, or from the perspective of the creation of sedition and sectarianism, activities that attempt to break the social cohesion within Islam and the believers, and that only serves the agenda of the enemies, not just of Islam, but of humanity.

The Broader Framework of Correction

Tabyeen does not merely react — it builds. As such, the confrontation of misguidance should be conducted through both individual and collective strategies, including:

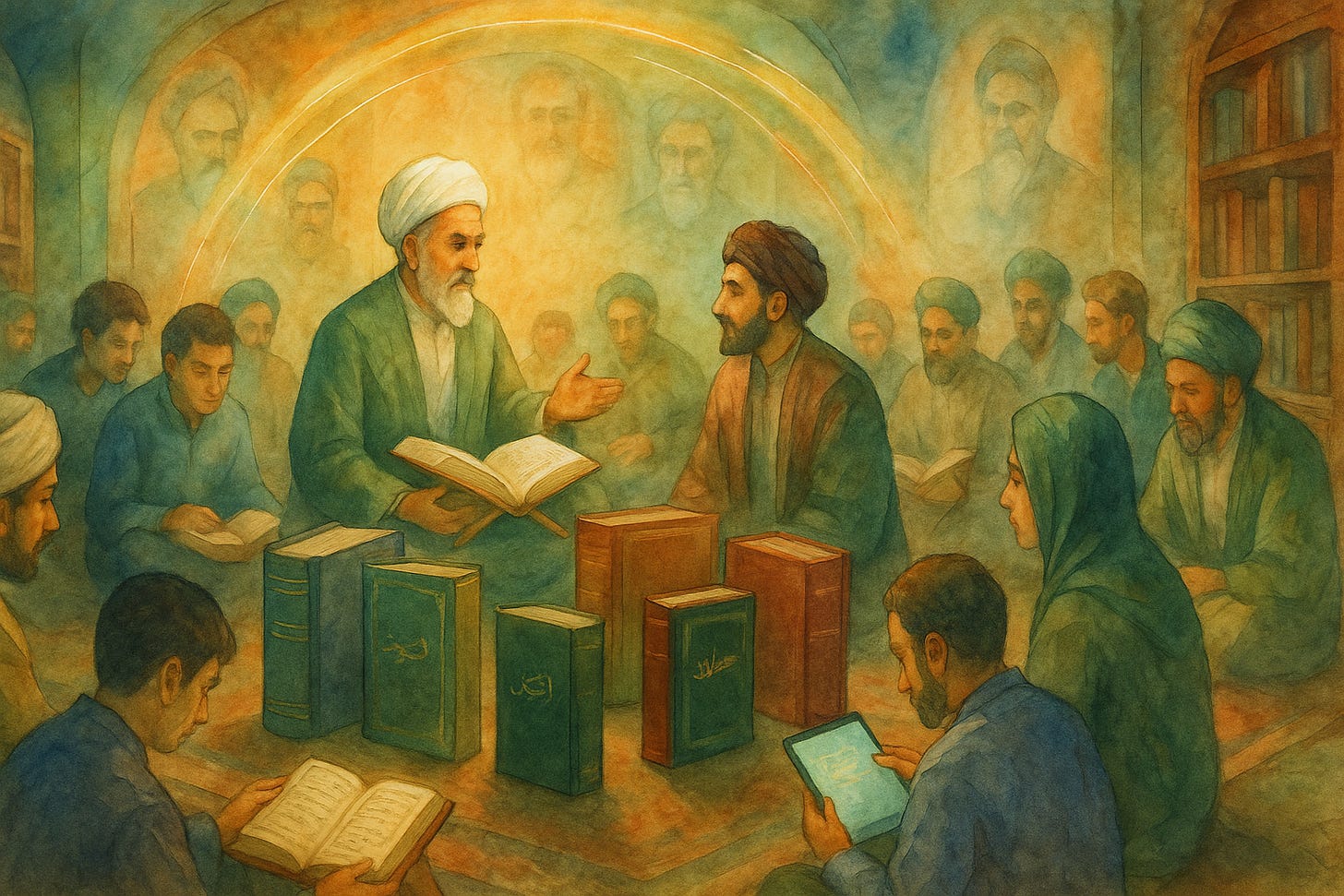

Clarification of Credentials and Intellectual Lineage

Audiences should be informed of the speaker’s educational background and intellectual formation.

If the speaker is a graduate of a recognised Islamic seminary (hawzah) — such as in Qom, Najaf, or elsewhere — their primary teachers should be identified.

Knowing a speaker’s teachers helps the congregation understand the interpretive framework they likely follow.

If the speaker is not hawzawi-trained, this should be stated transparently.

Holding a Ph.D. or academic qualification in a non-religious field (e.g. pharmacology or engineering) does not equate to expertise in Islamic theology or jurisprudence.

Even holding a Ph.D. in an Islamic subject from a secular university does not, in itself, confer religious authority. The Islamic seminaries (hawzat) are not merely educational institutions — they are institutions of soulcraft, dedicated to shaping character, refining ethics, and cultivating spiritual insight. As explored in our earlier sessions on wilayah, they are designed to produce not just scholars, but guardians of divine trust.

The aim is not exclusion but clarity: the community must know on what basis religious claims are made — and whether the authority behind them is grounded or assumed.

Pre-emptive Education

Encourage Quranic study with authentic tafsir (exegesis) (e.g. al-Mizan by Allamah Tabatabai, or Tafsir-e-Nemuneh by Ayatullah Makarem-Shirazi).

Promote deep engagement with reliable hadeeth collections (e.g. Usul al-Kafi, Tuhaf al-‘Uqul, Nahjul Balagha, etc).

Establish reading circles around the teachings of the Ahl al-Bayt, particularly among youth and those new to religious thought.

Critical Thinking Development

Equip audiences with logical reasoning tools: recognising weak arguments, false analogies, and emotional manipulation.

Train congregants to gently ask: “What is the evidence for this claim?” or “Is this consistent with the Quran and Sunnah?” or “Is this in line with the Quran and the teachings of the Ahl al-Bayt?”.

Community Forums

Create spaces for open, respectful dialogue with real scholars who are both learned and humble.

Contrast these forums with one-sided monologues on the minbar that leave no room for clarification or questioning.

Respectful Correction

If one has private access to the speaker, share concerns calmly - but firmly - and cite sources.

In sensitive public situations, correction can occur indirectly through a subsequent speech by another scholar — one that addresses the same topic, presents the correct position, and avoids naming individuals.

Imam Ali (peace be upon him) once said:

إِذَا ظَهَرَتِ الْبِدَعُ فَعَلَى الْعَالِمِ أَنْ يُظْهِرَ عِلْمَهُ، وَإِلَّا فَعَلَيْهِ لَعْنَةُ اللَّهِ

“When innovations appear, it is obligatory upon the scholar to manifest his knowledge. Otherwise, upon him is the curse of God.”

This responsibility is not limited to scholars — it applies to all who have the knowledge, access, and influence to correct. Even laypeople, if equipped with basic sources and decorum, have a role to play in the collective safeguarding of truth.

The Audience and the Authority: How to Recognise and Resist Religious Manipulation

Clarification (tabyeen) is not a one-way act. It is not the sole duty of the speaker, nor the scholar, nor the cleric.

It is also the sacred responsibility of the audience — those who hear, absorb, and act upon what is conveyed from the pulpit.

For the minbar is a site of trust, and that trust is shared: the speaker is entrusted with the delivery of truth, and the listener is entrusted with its discernment.

In many cases, the corruption of religious speech continues unchallenged not because people are malicious, but because they are deferential.

A speaker may utter an obvious fabrication, reference a source that does not exist, or distort a verse — and yet the congregation remains silent, unsure whether they are even permitted to ask a question.

This silence is not always piety.

Sometimes, it is a learned helplessness — a form of internalised clericalism that grants the speaker an aura of infallibility, even when he speaks error.

The Danger of Blind Obedience

The Quran repeatedly condemns those who followed their leaders blindly, excusing their own sins by appealing to the status of those who misled them:

وَقَالُوا رَبَّنَا إِنَّا أَطَعْنَا سَادَتَنَا وَكُبَرَاءَنَا فَأَضَلُّونَا السَّبِيلَا

And they will say, ‘Our Lord! Indeed, we obeyed our leaders and elders, but they led us astray from the path.’

— Quran, Surah al-Ahzaab (the Chapter of the Confederates) #33, Verse 67

And again:

اتَّخَذُوا أَحْبَارَهُمْ وَرُهْبَانَهُمْ أَرْبَابًا مِّن دُونِ اللَّهِ

They took their rabbis and monks as lords besides God.

— Quran, Surah al-Tawbah (the Chapter of the Repentance) #9, Verse 31

Imam al-Sadiq (peace be upon him) was asked about this verse. He explained that they did not worship the rabbis literally, but rather:

أَحَلُّوا لَهُمْ الْحَرَامَ وَحَرَّمُوا عَلَيْهِمُ الْحَلَالَ فَاتَّبَعُوهُمْ

“They made the unlawful lawful and the lawful unlawful, and the people obeyed them — that was their worship.”

This is the crux of the matter.

When audiences accept whatever is said from the pulpit without scrutiny, without verifying it against the Quran and the authentic teachings of the Ahl al-Bayt, they risk becoming complicit in the very distortion they lament.

Imam al-Baqir (peace be upon him) offered a golden principle:

كُلُّ شَيْءٍ يُرَدُّ إِلَى الْكِتَابِ وَالسُّنَّةِ، وَكُلُّ حَدِيثٍ لَا يُوَافِقُ كِتَابَ اللَّهِ فَهُوَ زُخْرُفٌ

“Everything must be referred back to the Book of God and the Sunnah. Any hadeeth that does not conform to the Book of God is mere ornamentation.”

Traits of a Responsible Scholar

So how can an audience distinguish between a scholar of sincerity and one of spectacle?

Here are some signs — not infallible, but indicative:

He speaks with humility: not using obscure references to confuse, nor name-dropping to impress.

He encourages questions: and never mocks a questioner, no matter how simple the inquiry.

He provides evidence: citing Quran and hadeeth, rather than relying on personal anecdotes or unverifiable tales.

He speaks with purpose: tailoring his message to the needs of the people, not merely performing rhetorical gymnastics.

He fears God more than the crowd: unafraid to challenge injustice, deviation, or ignorance, even if it risks his reputation.

Imam Ali (peace be upon him) declared:

أَيُّهَا النَّاسُ، إِنَّمَا يَجْمَعُ النَّاسَ الرِّضَا وَالسُّخْطُ، وَإِنَّمَا عَامَّةُ أَهْلِ الدُّنْيَا أَصْحَابُ اتِّبَاعٍ

“O people, what gathers people is either satisfaction or anger. Most people in this world are followers, not thinkers.”

— Nahjul Balagha68, Sermon 147

The challenge, then, is to become thinkers — not in the secular sense of intellectual pride, but in the spiritual sense of responsible discernment. This means studying, verifying, questioning, and — when necessary — challenging, always with adab (courtesy, politeness) and taqwa (God-consciousness, God-wariness).

Strategies for Addressing Irresponsible Pulpit Speech: From Private Advice to Public Clarification (Tabyeen)

The damage done by misleading speech from the pulpit is not easily undone.

False ideas can take root quickly, especially when delivered from a place of religious authority. But tabyeen — when done with wisdom, structure, and sincerity — can restore clarity and heal confusion.

Correcting irresponsible speech does not mean fuelling division or fostering chaos. It means serving the truth in a manner that protects both the message and the community.

Imam Ali (peace be upon him) once said:

إِنَّ أَوْلَى النَّاسِ بِاللَّهِ مَنْ أَطَاعَهُ، وَأَتْبَعَ أَمْرَهُ، وَإِنْ بَعُدَتْ نَسَبُهُ، وَأَبْعَدُهُمْ مِنَ اللَّهِ مَنْ عَصَاهُ وَإِنْ قَرُبَتْ قَرَابَتُهُ

“The closest of people to God is the one who obeys Him and follows His command, even if his lineage is distant; and the furthest from God is the one who disobeys Him, even if his kinship is close.”

— Nahjul Balagha69, Sermon 105

So what must we do when a scholar or speaker misuses the pulpit?

Pre-emptive Education and Empowerment

Before crisis arises, communities must be fortified through knowledge. The best defence against misguidance from the pulpit is a congregation that is literate in the Quran, conversant with hadeeth, and spiritually aware of its tradition.

Deepening Foundational Learning

The study of the Quran must be rooted in reliable tafaseer (exegeses), such as al-Mizan by Allamah Tabatabai or Tafsir-e-Namuneh by Ayatullah Makarem-Shirazi and others. Alongside this, access to the foundational Shia collections of hadeeth — such as al-Kafi, Tuhaf al-Uqul, and Nahjul Balagha — is essential.

Of course, these books should be studied under the supervision and guidance of a genuine scholar, one who has actually studied the Islamic sciences; as this will ensure that confusion and misguidance does not ensue.

Why is this important?

A congregant who is familiar with the teachings of Imam al-Sadiq (peace be upon him), for example, will be quick to detect a fabricated or culturally biased statement being falsely attributed to him. They will not be easily misled by emotional rhetoric or shallow appeals.

Furthermore, the insights of our senior scholars — such as Imam Khomeini, Imam Khamenei, Ayatullah Khui, Ayatullah Sistani, Ayatullah Jawad Amoli, Ayatullah Misbah Yazdi, and others — should be studied, discussed, and reflected upon regularly.

Though much of their work remains in Farsi, the barriers to access must be addressed. In an age where artificial intelligence and modern technology make real-time translation increasingly feasible, it is no longer acceptable for the oceans of guidance preserved in their writings, speeches and countless videos on YouTube and elsewhere to remain inaccessible - and therefore hidden - from the non-Farsi-speaking world.

This is a priority for Islamic revival.

Distinguishing Between True Scholars and Unqualified Speakers

In an age where information is abundant but verification is rare, not every speaker on Islamic matters is a scholar — nor should they be treated as one.

Islamic knowledge is not a hobby, nor is scholarship a self-appointed status.

True scholars are formed through disciplined years of study under recognised teachers in established institutions. They inherit a legacy of learning that stretches back to the Prophet Muhammad (peace and blessings be upon him and his family) through the chain of the Ahl al-Bayt and the great scholars of the ummah.

A person who enjoys reading Islamic books or watching lectures may benefit spiritually — but this does not make them a faqih, a muhaddith, a marja, an alem, a shaykh, or even a rudimentary muballegh (one who is qualified to propagate Islam); it merely makes them a person who enjoys reading books and watching lectures; nothing more and nothing less.

Just as a hawza graduate cannot claim expertise in aerospace engineering without formal training, likewise, a Ph.D. in engineering or medicine cannot speak authoritatively on Islamic jurisprudence or theology simply by virtue of their academic rank.

The Quran reminds us:

فَسْـَٔلُوا۟ أَهْلَ ٱلذِّكْرِ إِن كُنتُمْ لَا تَعْلَمُونَ

“So ask the People of the Reminder if you do not know.”

— Quran, Surah an-Nahl (the Chapter of the Bee) #16, Verse 43

This verse establishes the principle of specialisation. When you are ill, you consult a physician — not someone who has read a few medical articles.

Similarly, when dealing with matters of the soul, the law, or divine guidance, one must turn to those who are truly qualified.

Imam al-Sadiq (peace be upon him) warned:

مَنْ أَفْتَى النَّاسَ بِغَيْرِ عِلْمٍ لَعَنَتْهُ مَلَائِكَةُ السَّمَاوَاتِ وَالْأَرْضِ

“Whoever gives religious rulings to people without knowledge, the angels of the heavens and the earth curse him.”

Even more dangerous is when unqualified individuals ascend the pulpit, issuing rulings or opinions that mislead, divide, or distort the religion — all while cloaked in the appearance of religious authority.

This is not merely a matter of academic propriety.

It is a matter of soulcraft.

A scholar is not just a lecturer — they are a physician of the soul, entrusted with lives and legacies.

As Imam Ali (peace be upon him) described the true scholar:

يَا كُمَيْلُ، هَلَكَ خُزَّانُ الْأَمْوَالِ وَهُمْ أَحْيَاءٌ، وَالْعُلَمَاءُ بَاقُونَ مَا بَقِيَ الدَّهْرُ: أَعْيَانُهُمْ مَفْقُودَةٌ، وَأَمْثَالُهُمْ فِي الْقُلُوبِ مَوْجُودَةٌ

O Kumayl! The hoarders of wealth are dead even while they are alive, while the scholars remain for as long as time lasts. Their bodies may be gone, but their examples are present in the hearts.

— Nahjul Balagha72, Saying 147

And Imam as-Sadiq has beautifully detailed the outward signs that stem from this inner state:

صِفَةُ الْعَالِمِ أَنْ لَا يَمَلَّ مِنْ تَعَلُّمِ الْعِلْمِ... وَ أَنْ تَرَى الْحِلْمَ وَ الصَّمْتَ وَ الْإِخْبَاتَ وَ الْخُشُوعَ وَ الْخَشْيَةَ وَ الْهَيْبَةَ وَ الْحَيَاءَ قَدْ أَلْزَمَهُ نَفْسَهُ.

The characteristic of the scholar is that he does not tire of learning... and you see that forbearance, silence, humility, submissiveness, awe (of God), reverence, and modesty have become inseparable from his soul.

To treat anyone with an amameh (turban), an abaya (cloak), a beard, a microphone, or a few eloquent phrases as a religious authority is to risk turning one’s soul over to someone entirely unqualified to guide it.

A more direct and powerful narration comes from Imam al-Baqir, who quotes the Prophet Muhammad saying:

لَا تَجْلِسُوا عِنْدَ كُلِّ عَالِمٍ إِلَّا عَالِمٍ يَدْعُوكُمْ مِنْ خَمْسٍ إِلَى خَمْسٍ: مِنَ الشَّكِّ إِلَى الْيَقِينِ، وَ مِنَ الرِّيَاءِ إِلَى الْإِخْلَاصِ، وَ مِنَ الرَّغْبَةِ إِلَى الرَّهْبَةِ، وَ مِنَ الْكِبْرِ إِلَى التَّوَاضُعِ، وَ مِنَ الْغِشِّ إِلَى النَّصِيحَةِ.

Do not sit with every scholar except for a scholar who calls you from five things to five things:

From doubt to certainty.

From showing-off to sincerity.

From worldliness (desire) to asceticism (awe).

From arrogance to humility.

From deception to sincere advice.

— Al-Majlisi75, Bihar al-Anwar76, Volume 2, Chapter 9, Hadeeth 35

Therefore, the community must learn to gently ask:

“Has this speaker studied Islam formally? Who were their teachers? What is the scope of their knowledge?”

Such questions are not rude — they are responsible. Just as you would not entrust your health to a self-taught hobbyist, you should not entrust your soul, religion, indeed your deen (ideology), to one either.

Promoting Critical Thinking

It is not enough to teach people what to think; they must learn how to think.

The community must be trained to distinguish between divine decree and personal opinion, between authentic interpretation and speculative commentary.

This requires a solid ideological foundation, accompanied by access to vetted sermons, texts, and curricula. Beyond the content, it also necessitates spaces for dialogue — environments in which congregants can freely ask questions and at least one trustworthy, qualified scholar is available to respond with clarity and sincerity.

Critical thinking is not only an intellectual requirement; it is a spiritual shield. It is a life skill — one that protects the community from confusion, deception, and manipulation.

Why is this important?

When a speaker asserts, “This is how it must be,” a thoughtful listener should respectfully ask, “Where is the verse or narration for this?” or “What evidence supports this claim?”

And when something is said that clearly conflicts with reason or common sense, the audience should feel both permitted and obliged to say, “I’m sorry, but this does not make sense. Could you please clarify it or explain it in a way that resonates with both faith and reason?”

Establishing Community Study Circles

As noted earlier, dedicated spaces must be cultivated in which knowledgeable, humble, and sincere teachers can guide open discussion.

These study circles allow for mutual enrichment and foster a spiritually informed laity — one that can respectfully identify misstatements, seek clarification, and reinforce one another in truth.

Addressing the Issue with Wisdom

When a scholar errs, an impulsive or confrontational response can often cause more harm than good. Correction must be grounded in both principle and hikmah (wisdom).

The Quran instructs:

ادْعُ إِلِىٰ سَبِيلِ رَبِّكَ بِالْحِكْمَةِ وَالْمَوْعِظَةِ الْحَسَنَةِ ۖ وَجَادِلْهُم بِالَّتِي هِيَ أَحْسَنُ

“Invite to the way of your Lord with wisdom and good advice, and debate with them in the best manner.”

— Quran, Surah an-Nahl (the Chapter of the Bee) #16, Verse 125

Private Consultation

Where possible, one should engage the scholar in private. Raise concerns with decorum and evidence, prioritising clarity over confrontation.

For example, one might say:

“Respected Shaykh, your statement seemed to contradict [this verse/hadeeth]. Would you be open to discussing it further?”

This opens the door for dialogue without embarrassment or escalation.

Indirect Public Correction

If private engagement proves unfeasible or ineffective, another respected scholar may address the same topic in a subsequent sermon or gathering — presenting the correct Islamic position without naming the original speaker.

This approach preserves communal unity while fulfilling the obligation to clarify. The aim is not to win an argument, but to restore truth in a dignified manner.

Historical Precedent

The Imams (peace be upon them) regularly corrected misinterpretations and deviant ideas without singling out individuals. Unless an exceptional circumstance demanded it — as we will examine in future sessions of this series — they did not name the person responsible.

Instead, they addressed the content of the error, correcting the idea with eloquence, logic, and kindness.

This is the prophetic model of tabyeen — to expose falsehood by contrasting it with clear truth, not by inciting blame or division.

Thus, our approach must mirror theirs.

This is not about naming names, pointing fingers, or creating spectacle. It is about restoring clarity with humility. The focus is not on the individual who spoke, but on the misconception that was introduced — and on ensuring that the truth, not the ego, prevails.

Disseminating Correct Information Through Modern Media

Today’s battle for clarification extends far beyond the mosque.

Misinformation spreads quickly — and must be countered wherever it appears.

Write Articles: Well-researched responses grounded in Quran and hadeeth, as well as the teachings of the righteous Islamic scholars.

Produce Podcasts or Short Videos: Accessible formats that explain disputed topics clearly.

Create Infographics and Clips: Share visual content rooted in authentic sources to clarify misconceptions.

As an example: if a speaker promotes narrow or extreme views on women in Islam, a simple video quoting the Prophet’s honouring of Sayyedah Khadijah (peace be upon her) or Imam Ali’s devotion to Sayyeda Fatimah az-Zahra (peace be upon her) can powerfully rebut without controversy.

وَلَا تَكْتُمُوا الشَّهَادَةَ ۚ وَمَن يَكْتُمْهَا فَإِنَّهُ آثِمٌ قَلْبُهُ

“Do not conceal testimony. Whoever conceals it, his heart is sinful.”

— Quran, Surah al-Baqarah (the Chapter of the Cow) #2, Verse 283

Supporting Trusted Institutions

Not all pulpits are corrupt. There remain centres of learning and spiritual guidance that serve the people sincerely.

Support them financially and morally.

Refer others to their materials.

Defend them when they are attacked for speaking truth.

وَتَعَاوَنُوا عَلَى الْبِرِّ وَالتَّقْوَىٰ وَلَا تَعَاوَنُوا عَلَى الْإِثْمِ وَالْعُدْوَانِ

Cooperate with one another in righteousness and piety, and do not cooperate in sin and aggression.

— Quran, Surah al-Maidah (the Chapter of the Table Spread) #5, Verse 2

Consulting Senior Religious Authorities

When the issue is widespread, or the error repeated and harmful, recourse can be made to the Hawza and the Marjaiyyah, as well as to the Wali al-Faqih — the senior religious authorities and the Islamic Seminaries.

Write letters of concern, asking for guidance and clarification.

If needed, their offices may issue statements or engage the speaker directly.

As an example: if a speaker denies the legitimacy of taqleed (following a qualified jurist), and encourages anti-institutional rhetoric, then a response from the Marja may help anchor the confused.

Imam al-Sadiq (peace be upon him) said:

مَنْ أَفْتَى النَّاسَ بِغَيْرِ عِلْمٍ لَعَنَتْهُ مَلَائِكَةُ السَّمَاوَاتِ وَالْأَرْضِ

“Whoever gives religious rulings to people without knowledge, the angels of the heavens and the earth curse him.”

Conclusion

Clarification as the Fulfilment of the Pulpit’s Trust

The pulpit (minbar) is not wood and elevation — it is a covenant. It is not merely a platform from which speech is delivered, but a sacred station inherited from the Prophets and Imams, entrusted to those who are supposed to be heirs of divine guidance.

To ascend the minbar is to step into the shadow of the Messenger of God (peace and blessings be upon him and his family), of Imam Ali (peace be upon him) speaking in Kufa, of Imam al-Sajjad (peace be upon him) standing with chains around his neck in the court of Yazid — speaking truth with courage, dignity, and purpose.

This is why the Quran declares:

وَلَا تَقْفُ مَا لَيْسَ لَكَ بِهِ عِلْمٌ ۚ إِنَّ السَّمْعَ وَالْبَصَرَ وَالْفُؤَادَ كُلُّ أُولَٰئِكَ كَانَ عَنْهُ مَسْئُولًا

“Do not pursue that of which you have no knowledge. Indeed, the hearing, the sight and the heart — all of them will be questioned.”

— Quran, Surah al-Isra (the Chapter of the Night Journey) #17, Verse 36

Every speech from the pulpit is a testimony.

Every silence, too, is recorded.

The one who speaks from the minbar — while knowing the truth, but choosing not to say it — out of fear, reputation, or worldly gain — is not merely misguided; they are in breach of a divine trust.

إِنَّ اللَّهَ يَأْمُرُكُمْ أَن تُؤَدُّوا الْأَمَانَاتِ إِلَىٰ أَهْلِهَا

“Indeed, God commands you to render trusts to their owners.”

— Quran, Surah al-Nisa (the Chapter of the Women) #4, Verse 58

And to whom does the minbar belong, if not to the truth?

To whom is its trust owed, if not to God and the people?

Let us be clear: this is not a call to hostility, rebellion, or disruption.

It is a call to restoration.

To raise the standard of the minbar again — not by chasing celebrity scholars, but by returning to the example of those who clarified for the sake of God alone.

As Imam al-Sadiq (peace be upon him) said:

كُونُوا دُعَاةً لِلنَّاسِ بِغَيْرِ أَلْسِنَتِكُمْ

“Be callers to the truth — not merely with your tongues, but with your actions.”

To those who speak — speak with sincerity.

To those who listen — listen with discernment.

To all who care for this faith — know that tabyeen is not optional. It is a jihad — not of the sword, but of clarity. Not of conflict, but of courage. Not of anger, but of responsibility.

In the next part of this series, we will continue exploring the role of speech, knowledge, and responsibility by asking:

When is knowledge not enough?

What happens when a scholar knows the truth but does not live it? And how can the ummah discern between one who speaks about Islam, and one who embodies it?

وَقُلِ الْحَقُّ مِن رَّبِّكُمْ ۖ فَمَن شَاءَ فَلْيُؤْمِنْ وَمَن شَاءَ فَلْيَكْفُرْ

“And say: The truth is from your Lord — so let whosoever wills, believe; and whosoever wills, let them disbelieve.”

— Quran, Surah al-Kahf (the Chapter of the Cave) #18, Verse 29

Let us speak the truth — with courage, with adab (respect, decency, good manners), and above all, with yaqin (certainty).

Supplication-Eulogy #11: The Trust and the Pulpit

First Night of Arbaeen - The Trust and the Pulpit

In Your Name, O God — the Knower of the Secrets of Minbars and Martyrs,

The One before whom the hidden speech of hearts is louder than the sermons of the loudest pulpits.

O You who witness the betrayal of every robe donned in Your Name,

And You who record the silence of those who should have spoken!O God…

We have seen the minbars rise in splendour — but not in truth.

We have seen robes of honour conceal the cowardice of hearts.

We have seen Your words distorted by trembling tongues,

And the name of Husayn used as currency in bazaars of fame.O Lord, the pulpit has been desecrated —

Not by those who never knew it,

But by those who inherited it…

and betrayed it.We call upon You, O the Lord of Zaynab —

Whose chains were purer than their thrones,

Whose trembling was not in fear, but in fury.

Her words shattered palaces,

While the “scholars” remained silent in their safety.We call upon You, O the Sustainer of Sajjad —

Whose voice in the court of Yazid stood in place of a nation,

While those of knowledge bowed their heads and held their tongues.

O God, if that was the minbar of truth —

Then what are these stages we see today?O Everlasting One, when all things fade…

Did we not inherit a covenant?

Did we not promise — at every Ziyarat, at every Arbaeen —

That we would carry their message, clarify the truth, reject the oppressors?We bear witness that you fulfilled the covenant of God…

But we?

We have spoken too little — and cried too late.O God, You who hear the whispers beneath the shrines…

Where are the voices that defend the oppressed from the pulpits?

Where are the scholars who cry like Zaynab,

And bleed with their speech like Sajjad?Where are the preachers who fear You more than sponsors?

Who rise for truth, even when it breaks their comfort?Have we not read the Book You revealed?

“Do not pursue that of which you have no knowledge…”

— Quran, Surah al-Isra (the Chapter of the Night Journey) #17, Verse 36But today, O God… they pursue all — except knowledge.

They pursue fame, and call it faith.

They pursue followers, and call it fiqh.

They pursue applause… and call it adab.O God… forgive us.

Forgive us for every time we remained silent,

When the robe spoke lies.

Forgive us for being cowed by turbans,

When Your signs were being twisted.Forgive us for not crying out like Sayyedah Zaynab:

“I saw nothing but beauty…”

— while beauty itself was being dragged through the ashes.O God…

How long shall the minbar of truth remain vacant?Where is the caller of callers,

The clarifier of every confusion,

The one who would stand and declare what others fear to whisper?Where is the witness of Karbala who never forgot?

Where is the son of Husayn who cries blood for Husayn?Where is our Mahdi,

Your Proof upon Your earth?We are tired of shadows and cowards.

We are tired of silence that kills,

And speech that misguides.

We are tired of the stage where the minbar once stood.“O God, show us that noble countenance, that luminous presence…”

— Dua al-AhadLet him rise — not to please the people,

But to awaken them.Let him shatter every pulpit built upon betrayal.

Let him return the robe to those who speak with truth —

And burn the robes of those who speak for power.Let him silence the false and raise the sincere.

Let him call us to tabyeen —

Not with words alone, but with his presence.O our Master… our Imam… our hope in the dark:

We are not ready.

But we are trying.We have failed you,

But we love you.We fear we are among those whose sins have delayed your return,

Yet we cry out —

“O People of the Household of Mercy — by you, God accepts.”Accept us.

Cleanse us.

Use us.Let the blood of Husayn not cry in vain.

Let the chains of Zaynab not be mocked by the silence of the scholars.

Let the legacy of Sajjad not be forgotten by the inheritors of the minbar.And let us, O God,

be among those who clarify the truth,

carry the trust,

and await — not passively —

but with burning hearts and calloused hands,

the coming of the One who shall clarify all.Ameen, O Lord of the Worlds.

Amen, O Lord Sustainer of the Universes.

Amen, O Most Merciful of the Merciful

And from Him alone is all ability, and He has authority over all things.

Adapted from Ziyarat Arbaeen. The original from Ziyarat Arbaeen is in the singular form, I have taken the liberty of pluralising it:

The original Arabic and English translation is as follows:

اَلسَّلَامُ عَلَيْكَ يَا بْنَ رَسُولِ اللَّهِ

اَلسَّلَامُ عَلَيْكَ يَا بْنَ سَيِّدِ الْأَوْصِيَاءِ

أَشْهَدُ أَنَّكَ أَمِينُ اللَّهِ وَابْنُ أَمِينِهِ

عِشْتَ سَعِيداً وَمَضَيْتَ حَمِيداً وَمُتَّ فَقِيداً مَظْلُوماً شَهِيْداً

وَأَشْهَدُ أَنَّ اللَّهَ مُنْجِزٌ مَا وَعَدَكَ

وَمُهْلِكٌ مَنْ خَذَلَكَ وَمُعَذِّبٌ مَنْ قَتَلَكَ

وَأَشْهَدُ أَنَّكَ وَفَيْتَ بِعَهْدِ اللَّهِ

وَجَاهَدْتَ فِي سَبِيلِهِ حَتَّى أَتَاكَ الْيَقِينُ

فَلَعَنَ اللَّهُ مَنْ قَتَلَكَ وَظَلَمَكَ

وَلَعَنَ اللَّهُ أُمَّةً سَمِعَتْ بِذَلِكَ فَرَضِيَتْ بِهِ

اللَّهُمَّ إِنِّي أَشْهَدُكَ أَنِّي وَلِيٌّ لِمَنْ وَلَاكَ

وَعَدُوٌّ لِمَنْ عَادَاكَ

بِأَبِي أَنْتَ وَأُمِّي يَا بْنَ رَسُولِ اللَّهِPeace be upon you, O son of the Messenger of God.

Peace be upon you, O son of the Master of the Successors.I bear witness that you are the trustee of God and the son of His trustee.

You lived a blessed life, departed praiseworthy, and died a martyr, deprived and wronged.

And I bear witness that God will fulfil what He promised you,

and will destroy those who abandoned you, and punish those who killed you.

And I bear witness that you fulfilled the covenant of God,

and strove in His way until certainty (death) came to you.So may God’s mercy be away from those who killed you and wronged you,

and God’s mercy be away from the nation that heard of this and was pleased with it.O God, I make You my witness that I am a friend to those who befriend him (Husayn),

and an enemy to those who are hostile to him.

May my father and mother be sacrificed for you, O son of the Messenger of God.

I have made the following changes to the Arabic so as to pluralise:

أَشْهَدُ (ashhadu) - "I bear witness" (singular, first person)

Changed to نَشْهَدُ (nashhadu) - "We bear witness" (plural, first person). This is a change in the verb conjugation.

إِنِّي (inni) - "Indeed I" or "I am" (the ya at the end indicates "my" or "I")

Changed to إِنَّا (inna) - "Indeed we" or "We are" (the na at the end indicates "our" or "we").

وَلِيٌّ لِمَنْ وَلَاكَ (waliyyun li-man walaaka) - "a friend to those who befriend you" (singular noun "friend")

Changed to أَوْلِيَاءُ لِمَنْ وَلَاكَ (awliyaa'u li-man walaaka) - "friends to those who befriend you" (plural noun "friends").

وَعَدُوٌّ لِمَنْ عَادَاكَ (wa aduwwun li-man aadaaka) - "and an enemy to those who are hostile to you" (singular noun "enemy")

Changed to وَأَعْدَاءُ لِمَنْ عَادَاكَ (wa a’adaa’u li-man 'aadaaka) - "and enemies to those who are hostile to you" (plural noun "enemies").

بِأَبِي أَنْتَ وَأُمِّي (bi-abi anta wa ummi) - "May my father and mother be sacrificed for you" (literally "with my father and my mother, you")

Changed to بِآبَائِنَا وَأُمَّهَاتِنَا (bi-aabaa'inaa wa ummahaatinaa) - "May our fathers and our mothers be sacrificed for you."

أَبِي (abi) "my father" (singular possessive) became آبَائِنَا (aabaa'inaa) "our fathers" (plural noun + plural possessive pronoun).

أُمِّي (ummi) "my mother" (singular possessive) became أُمَّهَاتِنَا (ummahaatinaa) "our mothers" (plural noun + plural possessive pronoun).

Nahjul Balagha (Arabic: نهج البلاغة, "The Peak of Eloquence") is a renowned collection of sermons, letters, and sayings attributed to Imam Ali, the cousin and son-in-law of the Prophet Muhammad and the first Imam of the Muslims.

The work is celebrated for its literary excellence, depth of thought, and spiritual, ethical, and political insights. Nahjul Balagha was compiled by Sharif al-Radi (al-Sharif al-Radi, full name: Abu al-Hasan Muhammad ibn al-Husayn al-Musawi al-Sharif al-Radi), a distinguished Shia scholar, theologian, and poet who lived from 359–406 AH (970–1015 CE).

Sharif al-Radi selected and organised these texts from various sources, aiming to showcase the eloquence and wisdom of Imam Ali. The book has had a profound influence on Arabic literature, Islamic philosophy, and Shia thought, and remains a central text for both religious and literary study

Allamah Muhammad Baqir al-Majlisi (1037 AH / 1627 CE - 1110 or 1111 AH / 1698 or 1699 CE), a highly influential Shia scholar of the Safavid era, is best known for compiling Bihar al-Anwar, a monumental encyclopedia of Shia hadeeth, history, and theology that remains a crucial resource for Shia scholarship; he served as Shaykh al-Islam, promoting Shia Islam and translating Arabic texts into Persian, thereby strengthening Shia identity, though his views and actions, particularly regarding Sufism, have been subject to debate.

Mir’aat al-Uqul fi Sharh Akhbar Aal al-Rasul (مرآة العقول في شرح أخبار آل الرسول), meaning "The Mirror of Intellects in Explaining the Narrations of the Household of the Messenger," is a profound and comprehensive commentary on al-Kafi by Shaykh al-Kulayni, one of the four foundational books of Shia hadeeth. Authored by the illustrious Allamah Muhammad Baqir al-Majlisi (d. 1111 AH/1699 CE), this work stands as a testament to his unparalleled scholarship and dedication to preserving and elucidating the teachings of the Ahl al-Bayt (peace be upon them). In Mir’aat al-Uqul, Allamah Majlisi meticulously examines each hadeeth, providing linguistic analyses, jurisprudential insights, theological explanations, and critical evaluations of the chain of narration (sanad) and the text (matn). His commentary often delves into the various interpretations and scholarly opinions, offering a rich tapestry of knowledge that helps readers grasp the deeper meanings and implications of the narrations.

This magnum opus is indispensable for students and scholars of hadeeth, as it not only clarifies complex narrations but also reflects the intellectual rigour and vast knowledge of one of Shia Islam's most prominent figures. Through Mir’aat al-Uqul, Allamah Majlisi aimed to make the profound wisdom contained within al-Kafi more accessible, ensuring that the authentic teachings of the Imams (peace be upon them) continue to guide generations of believers. His meticulous approach and comprehensive scope make Mir’aat al-Uqul a vital resource for understanding the nuances of Shia jurisprudence, ethics, and beliefs, solidifying its place as a cornerstone in the Shia scholarly tradition.

Shaykh al-Hurr al-Ameli (1033–1104 AH/1624–1693 CE) was a towering Imami scholar and traditionist, best known for his monumental work Wasail al-Shia, a comprehensive compilation of Shia hadeeths on jurisprudence. Born in Jabal Amel (modern-day Lebanon), he later migrated to Iran, where he became a prominent figure in the Safavid scholarly circles. His Wasail systematically organises over 35,000 narrations from the Ahl al-Bayt into fiqh chapters, serving as an indispensable reference for Shia jurists. A devout follower of the Imams, he also authored works on theology, rijaal (hadeeth narrators), and pilgrimage rituals, embodying the scholarly tradition of Twelver Shi’ism. His legacy endures as a bridge between early Shia hadeeth literature and later Usuli scholarship.

Wasail al-Shia (وسائل الشيعة), compiled by Shaykh al-Hurr al-Ameli, is one of the most authoritative and comprehensive collections of Shia hadeeths on Islamic jurisprudence (fiqh). Officially titled Tafsil Wasail al-Shia ila Tahsil Masail al-Sharia, this monumental work meticulously organises over 35,000 narrations from the Ahl al-Bayt into thematic chapters, covering all aspects of religious practice—from purification and prayer to social and economic rulings. Unlike earlier hadeeth collections, Wasā’il serves as a systematic fiqh manual, drawing primarily from the Kutub al-Arba’a (the Four Books of Shia hadeeth) while incorporating additional chains and commentaries. Its unparalleled structure and reliability have made it a cornerstone of Shia scholarship, widely relied upon by jurists (fuqaha) and students of Islamic law. The work also includes the author’s critical notes on hadeeth authenticity, reflecting the rigour of Imami scholarship. To this day, it remains an essential reference for deriving legal rulings and understanding the teachings of the Prophet and the Imams.

See Note 3.

Bihar al-Anwar (Seas of Light) is a comprehensive collection of hadeeths (sayings and traditions of Prophet Muhammad and the Imams) compiled by the prominent Shia scholar Allamah Muhammad Baqir al-Majlisi.

This extensive work covers a wide range of topics, including theology, ethics, jurisprudence, history, and Quranic exegesis, aiming to provide a complete reference for Shia Muslims.

Allamah Majlisi began compiling the Bihar al-Anwar in 1070 AH (1659-1660 CE) and completed it in 1106 AH (1694-1695 CE), drawing from numerous sources and serving as a significant contribution to Shia Islamic scholarship.

Shaykh al-Kulayni (c. 864–941 CE / 250–329 AH), whose full name is Abu Jaʿfar Muhammad ibn Yaqub al-Kulayni al-Razi, was a leading Shia scholar and the compiler of al-Kafi, the most important and comprehensive hadeeth collection in Shia Islam.

Born near Rey in Iran around 864 CE (250 AH), he lived during the Minor Occultation of the twelfth Imam (874–941 CE / 260–329 AH) and is believed to have had contact with the Imam’s deputies.

Shaykh Al-Kulayni traveled extensively to collect authentic narrations, eventually settling in Baghdad, a major center of Islamic scholarship.

His work, al-Kafi, contains over 16,000 traditions and is divided into sections on theology, law, and miscellaneous topics, forming one of the "Four Books" central to Shia hadeeth literature.

Renowned for his meticulous scholarship and piety, Shaykh al-Kulayni’s legacy remains foundational in Shia studies, and he is buried in Baghdad, where he died in 941 CE (329 AH).

Al-Kafi is a prominent Shia hadeeth collection compiled by Shaykh al-Kulayni (see Note 1) in the first half of the 10th century CE (early 4th century AH, approximately 300–329 AH / 912–941 CE). It is divided into three sections:

Usul al-Kafi (theology, ethics),

Furu' al-Kafi (legal issues), and

Rawdat al-Kafi (miscellaneous traditions)

Containing between 15,000 and 16,199 narrations and is considered one of the most important of the Four Books of Shia Islam

See Note 9.

See Note 10.

The “Faysal Edition” of Nahjul Balagha refers to the critical edition prepared by Dr Subhi al-Salih (often called the “Faysal” or “Subhi al-Salih” edition), which is highly regarded among scholars and students of Islamic studies. What distinguishes this edition from earlier prints is its rigorous academic approach: Dr al-Salih meticulously compared various manuscripts, provided detailed footnotes, and included clarifications on difficult words and phrases. He also offered a careful arrangement of sermons, letters, and sayings, often with references to their sources in earlier hadeeth and historical works. This scholarly attention to authenticity and context has made the Faysal Edition a preferred reference for those seeking a reliable and well-annotated text of Nahjul Balagha, helping readers engage more deeply with the profound teachings of Imam Ali (peace be upon him).

See Note 9.

See Note 10.

See Note 5.

See Note 6.

See Note 3.

See Note 8.

See Note 13.

See Note 9.

See Note 10.

See Note 9.

See Note 10.

See Note 9.

See Note 10.

Imam Abu Abdullah Muhammad ibn Yazid ibn Majah al-Qazwini (209–273 AH/824–887 CE) was a famous Persian hadeeth scholar and the author of Sunan Ibn Majah, one of the Kutub al-Sittah (Six Major Hadeeth Collections). Born in Qazvin (modern-day Iran), he traveled widely to study hadeeth, learning from great scholars like al-Bukhari and Muslim, and teaching others like Abu Ya'la al-Khalili. His Sunan contains 4,341 hadeeths, organised by topics such as worship, law, and daily life. While some hadeeths in it are weak, its place among the Six Books shows its importance in Sunni Islam. Scholars like al-Dhahabi praised Ibn Majah’s careful work, and his collection remains a key reference for hadeeth studies and Islamic rulings.