[1] The Joy of Fasting - The Great Migration - From the Self to God

The Joy of Fasting: A Special Series for the Month of Ramadhan 1447 / 2026 Studying the Subject of Fasting and Attaining Closeness to God, Especially during the blessed Month of Ramadhan

In His Name, the Most High

Introduction

Every year, the Month of Ramadhan arrives and we prepare for it the same way.

We stock the freezer.

We adjust our sleep schedules.

We tell ourselves that this year will be different — this year we will read more Quran, pray with more attention, waste less time.

And then the month begins, and within days, the fast becomes what it always becomes: an exercise in endurance.

We watch the clock.

We count the hours until iftar.

We manage our hunger, our headaches, our caffeine withdrawals.

We survive the month.

And when Eid arrives, we feel relief — not transformation.

We lost a few pounds.

We didn’t gain proximity to God.

Something has gone wrong.

Not with the fast itself — the fast is a divine institution, designed by the One who knows us better than we know ourselves.

What has gone wrong is with our understanding of what the fast is for.

We have reduced it to its mechanics — don’t eat, don’t drink, don’t do certain things between these two times — and in doing so, we have mistaken the vehicle for the destination.

It is as though someone handed us a plane ticket to the most beautiful city on earth, and we spent the entire journey studying the seat cushion.

The scholars of this tradition — and I mean the ones who didn’t just study the fast but lived it at its deepest level — describe something radically different from what most of us experience.

Imam Khomeini, in his Adab as-Salat (The Disciplines of Prayer), speaks of fasting as a migration of the soul, a journey from the prison of the ego toward the presence of the Divine.

Allamah Tabatabai, in his Lubb al-Lubab (The Innermost Essence), maps out the stages of that journey with the precision of a cartographer — surrender, faith, migration, struggle — and tells us that the destination is nothing less than union with God.

Ayatullah Bahjat, a man who spent decades in the depths of worship, speaks of something he calls halawat al-iman — the sweetness of faith — and insists that this sweetness is not a metaphor.

It is not poetry.

It is an experience as real as the hunger in your stomach, and infinitely more satisfying.

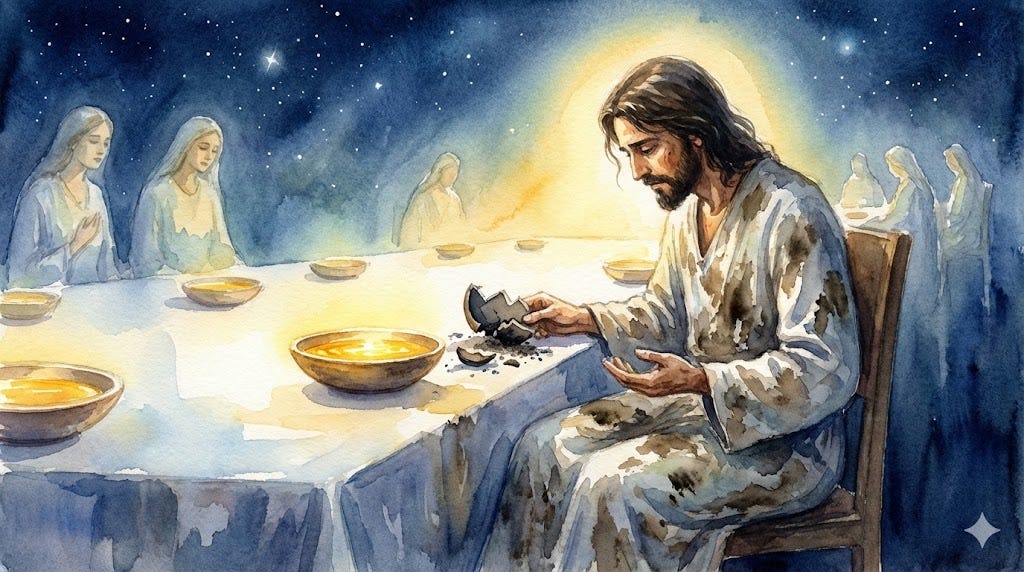

Ayatullah Jawadi-Amoli reads the famous hadith —

«الصَّوْمُ لِي وَأَنَا أُجْزِي بِهِ»

“Fasting is for Me, and I am its reward.”

— Al-Tusi, Tahdhib al-Ahkam (The Refinement of the Rulings), Volume 4, Page 152

— Al-Saduq, Man La Yahduruhu al-Faqih (For Those In Whose Presence There is No Jurist), Volume 2, Page 75

— Al-Bukhari, Sahih, Hadeeth 1904 (and 5927)

— Al-Nayshabouri, Sahih Muslim, Hadeeth 1151

— and pauses on those last words.

I am its reward.

Not paradise.

Not forgiveness.

Not blessings.

God Himself.

The reward of the fast is the arrival at the Beloved.

This is what the tradition is offering us.

Not thirty days of discomfort in exchange for divine credit.

Not a spiritual transaction.

A journey.

A migration from the smallest, most suffocating place we know — ourselves — to the most vast, most generous, most luminous presence there is.

And the scholars tell us — every single one of them, across centuries and continents — that the journey is not bitter.

It is joyful.

Not in spite of the hunger, but through it.

The hunger is the door.

What lies on the other side is what they call joy.

That is what this series is about.

Over five sessions, we are going to walk that road together — not as academics examining it from a distance, but as travellers setting out on it.

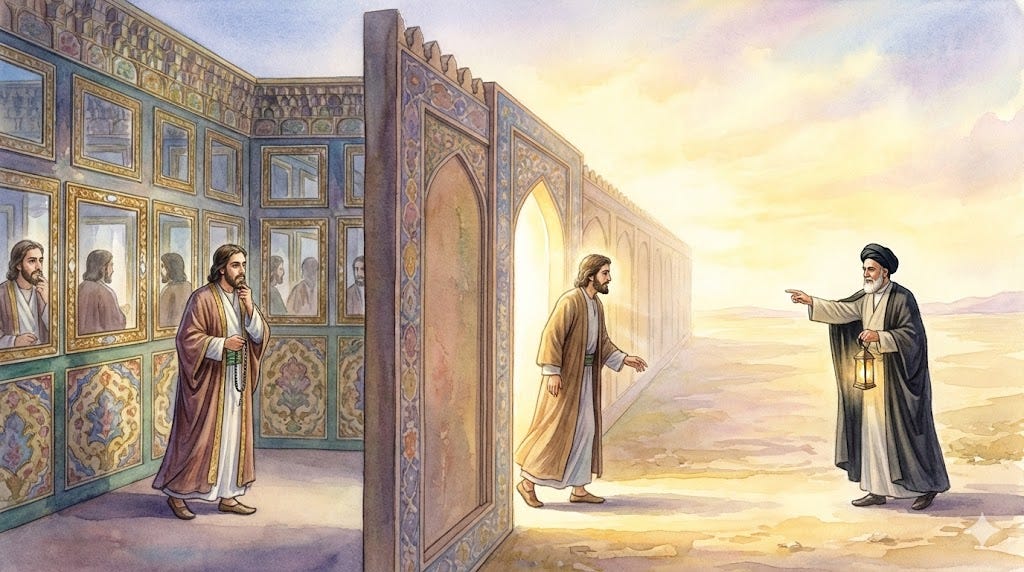

Tonight, in this first session, we begin with the most fundamental question: what does it mean to leave?

What is the “house of the self” that the Quran speaks of, and what does it look like to walk out of it?

We will call this session The Great Migration — because fasting, properly understood, is not an act of staying still.

It is an act of movement.

It is hijrah.

In the second session, we clean the mirror of the heart — the mirror that a year’s worth of sin and distraction has covered in dust.

We will call it The Purification of the Mirror.

In the third, we arrive at the banquet — because God has not invited us to the month of Ramadhan to starve us but to feed us with light and recognition.

We will call it The Feast of Light.

In the fourth, we confront the ego’s counterattack — the irritability, the self-pity, the whisper that says “you’ve done enough.”

We will call it Sacrifice and Self-Building.

And in the fifth and final session, we arrive — God willing — at the destination the entire month has been pointing toward.

Liqa’ Allah.

The Meeting with God.

Not after death, but now, in this life, on the nights of Qadr.

And we will ask: how do we keep the door open after the month closes?

Five sessions.

One journey.

From the house of the self to the presence of the Divine.

And the first step is tonight.

But before we take that step, I want to be honest with you about something.

This series is not going to tell you that the road is easy.

The scholars we are drawing from — Imam Khomeini, Allamah Tabatabai, Ayatullah Bahjat, Ayatullah Jawadi-Amoli, Mirza Jawad Maliki Tabrizi, Shaykh Panahian — they are unflinching in their honesty about how difficult the inner journey is.

The contemporary scholar Shaykh Alireza Panahian describes it in stages: first comes bitterness — the raw difficulty of saying no to the ego.

Then comes neutral effort — going through the motions without feeling much at all.

Then comes sweetness — the moment when obedience itself becomes a pleasure.

And then, finally, intimacy — the quiet, unshakeable nearness to God that the saints describe.

Most of us, if we are honest, live our Months of Ramadhan in the first two stages.

We endure the bitterness.

We settle into the neutral.

And then the month ends before we ever taste the sweet.

The invitation of this series is to push further.

Not through willpower — the ego is stronger than your willpower — but through understanding.

If you know where the road leads, you can bear the bitterness of the first few miles.

If you know that sweetness is real — not theoretical, not reserved for saints, but available to anyone who genuinely walks — then perhaps this Month of Ramadhan, you will keep walking past the point where you usually stop.

That is what I am asking of you tonight and over the coming weeks.

Not perfection.

Not sainthood.

Just one more step than last year.

One more step past the comfortable.

One more step out of the house of the self.

Let us begin.

Video of the Sermon (Majlis/Lecture)

Audio of the Sermon (Majlis/Lecture)

The Human Entry Point

We all know what it feels like to be stuck.

Not stuck in traffic, not stuck in a queue — stuck in yourself.

Stuck in a pattern you didn’t consciously choose but somehow can’t stop repeating.

You know the feeling.

It is the argument you have with your spouse where you hear yourself saying the same thing you said last time, in the same tone, with the same result, and some part of you is watching from above thinking why am I doing this again?

It is the phone you pick up without thinking, the scroll that was supposed to last two minutes and lasts forty, the hollow feeling afterwards that you can’t quite name.

It is the anger that flares over nothing — someone cuts you off in traffic, someone says something careless, and the reaction is instant, disproportionate, and entirely predictable.

You have been reacting this way for years.

You will react this way tomorrow.

It is, if we are being honest, the quiet horror of realising that most of what you do in a day is not chosen.

It is automated.

You are not driving the car.

The car is driving itself, and you are sitting in the back seat watching the scenery repeat.

The Quran has a name for this.

It calls it a house.

وَمَن يَخْرُجْ مِن بَيْتِهِ مُهَاجِرًا إِلَى ٱللَّهِ وَرَسُولِهِ ثُمَّ يُدْرِكْهُ ٱلْمَوْتُ فَقَدْ وَقَعَ أَجْرُهُ عَلَى ٱللَّهِ ۗ وَكَانَ ٱللَّهُ غَفُورًا رَّحِيمًا

“And whoever leaves his home migrating toward God and His Messenger, and then death overtakes him, his reward has already fallen upon God. And God is All-Forgiving, Most Merciful.”

— Quran, Surah al-Nisa (the Chapter of the Women) #4, Verse 100

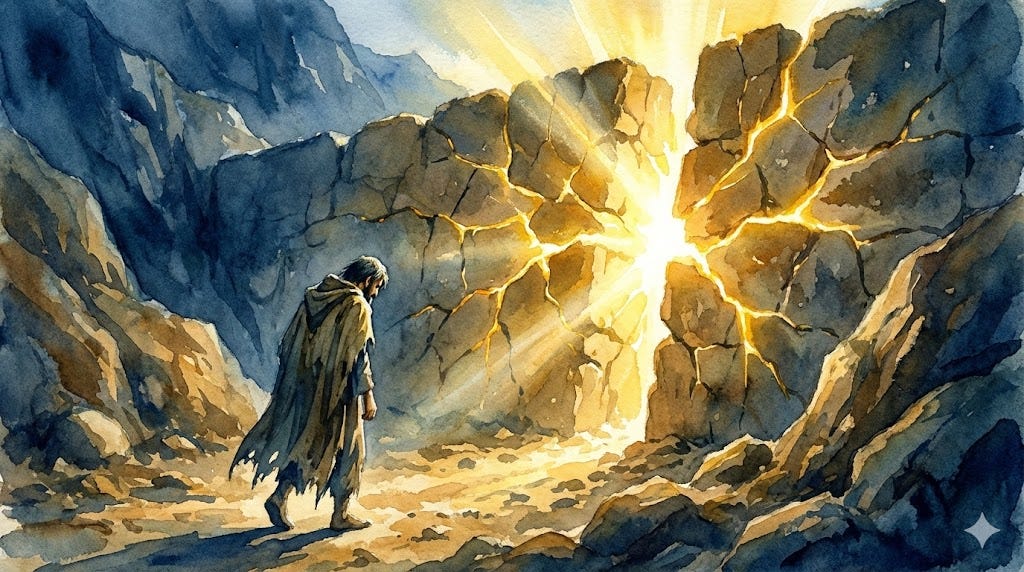

Specifically, it speaks of leaving your house — wa man yakhruj min baytihi — whoever leaves his home, migrating toward God.

The scholars of the inner tradition read that verse and say: the “house” is not your flat in London or your apartment in Toronto.

The house is you.

The house is the structure of habits, reactions, desires, and demands that you have built around yourself over a lifetime, brick by brick, until the walls are so familiar you have forgotten they are walls at all.

You think the walls are you.

You think the patterns are your personality.

You think the anger, the craving, the restlessness — that is just who I am.

And then the month of Ramadhan arrives.

And for thirty days, God asks you to do something deceptively simple: stop eating.

Just stop.

And in that stopping, something extraordinary is supposed to happen.

The walls are supposed to crack.

The patterns are supposed to falter.

The autopilot is supposed to glitch.

Because when you deny the body its most basic demand — feed me — you are, for the first time, asserting that you are not a passenger.

You are saying to the car:

I am driving now.

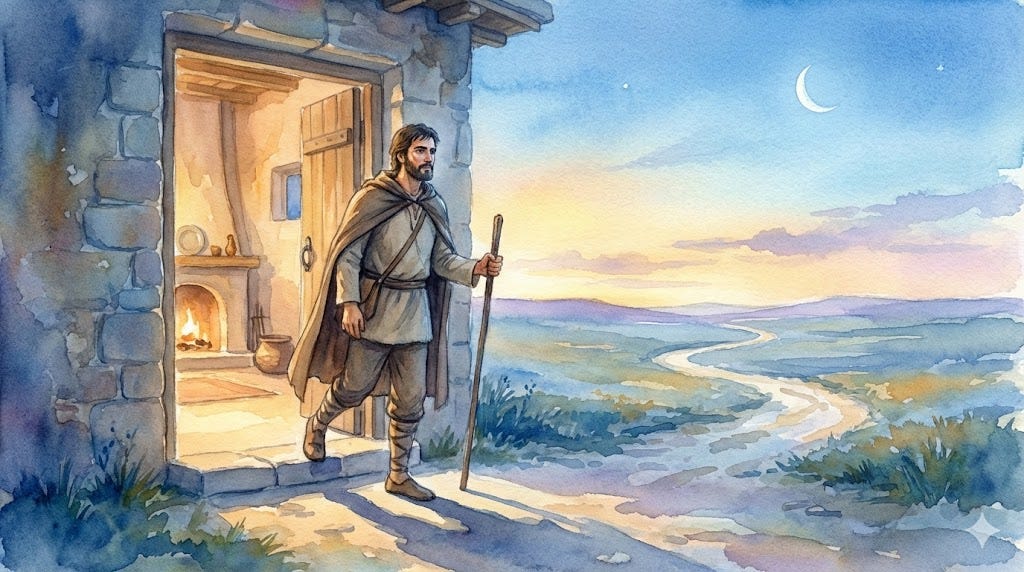

But here is the question that most of us never ask, the question that this entire session is built around: if fasting is about leaving the house of the self — if it is a migration, a movement, a departure — then where are we going?

What is on the other side of the walls?

What happens when the shell cracks?

The tradition has an answer.

And the answer is not what you might expect.

It is not punishment.

It is not emptiness.

It is not the grim satisfaction of having endured.

The answer, according to every scholar we will hear from tonight, is joy.

A joy so specific, so unmistakable, that the ones who have tasted it cannot stop talking about it.

They call it halawa — sweetness.

And they say it makes every other pleasure you have ever known feel like a photograph of a meal compared to the meal itself.

Tonight, we go looking for that sweetness.

And the first step is understanding what we are leaving behind.

Movement 1: The Core Concept — What Is Spiritual Migration?

Before we open the Quran, I want to share with you a passage that stopped me in my tracks.

The Original Homeland

It comes from the very first page of one of the most remarkable books in our tradition — Al-Muraqabat (The Acts of Watchfulness), written by the great scholar and mystic Mirza Jawad Maliki Tabrizi.

This is a man who dedicated his life to mapping the inner dimensions of worship, and he begins his masterwork not with a legal ruling or a theological argument, but by addressing his own soul:

«اعلم - أيها العبد اللئيم الذميم البطال - أن هذه الأيام والأوقات - التي ولدت فيها إلى أن تموت - بمنزلة منازل سفرك إلى وطنك الأصلي الذي خلقت بمجاورته والخلود فيه، وإنما أخرجك ربك ومالكك وولي أمرك إلى هذا السفر لتحصيل فوائد كثيرة وكمالات جمة عقيقة، لا يحيط بها عقول العقلاء وعلوم العلماء وأوهام الحكماء، من بهاء ونور وسرور وحبور، بل وسلطنة وجلال وبهجة وجمال وولاية وكمال»

“Know — O lowly, insignificant, idle servant — that these days and moments, from when you were born until you die, are like the stations of your journey to your original homeland — the homeland you were created to dwell beside and remain in forever. And your Lord, your Owner, and the Master of your affair sent you out on this journey to acquire many benefits and great perfections that the minds of the wise, the knowledge of scholars, and the imaginations of philosophers cannot encompass — of splendour and light, joy and gladness; nay, of sovereignty and majesty, delight and beauty, authority and perfection.”

— Mirza Jawad Maliki Tabrizi, Al-Muraqabat (The Acts of Watchfulness), A’mal al-Sana’ (The Devotional Acts of the Year), Page 7

Listen to what he is saying.

He is saying that you — right now, tonight, sitting wherever you are sitting — are already on a journey.

You have been on it since the day you were born.

Every day of your life is a manzil — a station on a road.

And the road is not random.

It is not the meaningless repetition of Monday, Tuesday, payday, weekend.

It leads somewhere.

It leads to what he calls your watan asli — your original homeland.

The place you were made for.

The place beside which you were created to dwell forever.

And notice what he says is waiting for you there.

He does not say obligation.

He does not say punishment.

He does not say a reckoning.

He says baha’ wa nur — splendour and light.

Surur wa hubur — joy and gladness.

Saltanah wa jalal — sovereignty and majesty.

Bahjah wa jamal — delight and beauty.

This is not the language of deprivation.

This is the language of someone describing a homecoming so magnificent that the finest minds in human history cannot wrap their heads around it.

But here is the problem.

Most of us are asleep on this journey.

We are passengers on a train, staring at our phones, not knowing where we are headed and not particularly caring to find out.

The days pass — one station after another — and we barely glance out of the window.

We are so absorbed in the distractions of the carriage that we have forgotten we are going somewhere.

And then the Month of Ramadhan arrives.

And the Month of Ramadhan is the stretch of the road where God shakes us awake and says:

Pay attention.

You are approaching something magnificent.

Do not sleep through this part.

The Verse of Departure

Now, if life is a journey and the Month of Ramadhan is its most critical stretch, then the Quran gives us the language for what we must do at this point on the road.

We have already heard the verse — Surah al-Nisa (the Chapter of the Women), Verse 100:

وَمَن يَخْرُجْ مِن بَيْتِهِ مُهَاجِرًا إِلَى ٱللَّهِ وَرَسُولِهِ ثُمَّ يُدْرِكْهُ ٱلْمَوْتُ فَقَدْ وَقَعَ أَجْرُهُ عَلَى ٱللَّهِ ۗ وَكَانَ ٱللَّهُ غَفُورًا رَّحِيمًا

“And whoever leaves his home migrating toward God and His Messenger, and then death overtakes him, his reward has already fallen upon God. And God is All-Forgiving, Most Merciful.”

— Quran, Surah al-Nisa (the Chapter of the Women) #4, Verse 100

— in which God speaks of those who leave their homes, migrating toward Him.

On the surface, this verse was revealed about the physical migration — the companions who left Makkah for Madinah, who abandoned their homes, their wealth, their families, for the sake of God.

That is the hijrah al-suriyyah — the formal, physical migration.

And it is noble, and it is honoured, and it is real.

But the scholars of the inner tradition say: there is another migration hidden inside this verse.

And it is harder than crossing any desert.

Imam Khomeini — and I want us to sit with his words carefully, because this passage is the theological foundation of everything we will discuss tonight — writes the following in his Adab as-Salat (The Disciplines of the Prayer):

«فالهجرة الصورية وصورة الهجرة عبارة عن هجرة البدن “المنزل الصوري” الى الكعبة أو الى مشاهد الأولياء، والهجرة المعنوية هي الخروج من بيت النفس ومنزل الدنيا الى الله ورسوله... وما دام للسالك تعلّق ما بنفسانيته وتوجه منه الى إنيته فليس هو بمسافر وما دامت البقايا من الانانية على امتداد نظر السالك وجدران مدينة النفس... فهو في حكم الحاضر لا المسافر»

“Formal migration is the migration of the body from the physical house to the Ka’bah or the shrines of the Saints. But spiritual migration — al-hijrah al-ma’nawiyyah — is the exit from the ‘House of the Self’ and the abode of the world toward God and His Messenger. As long as the wayfarer has any attachment to his own ego and turns toward his own ‘I-ness’, he is not a traveller. And as long as remnants of egoism remain in the wayfarer’s vision, and the walls of the ‘City of the Self’ are visible, he is judged as one who is stationary — not a traveller.”

— Imam Khomeini, Adab al-Salat (The Disciplines of the Prayer), Page 32

Read that last line again.

He is judged as one who is stationary — not a traveller.

The Arabic is devastating in its precision: hadir, not musafir.

Present, not journeying.

Stuck, not moving.

You can fly to Makkah and perform every ritual with flawless precision, and if the walls of the ego are still standing, if the “I” is still firmly on its throne, you have not moved an inch.

You are hadir.

Stationary.

You went nowhere.

And this is the reframe that changes everything about how we understand the fast.

Fasting is not primarily an act of stopping.

It is an act of moving.

It is hijrah.

A person who stops eating and drinking but remains imprisoned inside their arrogance, their selfishness, their compulsive need for control and validation — that person has not fasted.

Not really.

They have performed the form of the fast while remaining stationary in the house of the self.

They are, in Imam Khomeini’s unsparing language, hadir — present in the ego, absent from the journey.

But a person who stops eating and, in that stopping, feels something loosen — feels the grip of a habit weaken, feels the walls of a pattern thin, feels even for a moment that they are not their anger, not their craving, not their need to be right — that person has taken a step.

A single step out of the house.

And that single step, the tradition tells us, is worth more than a thousand rituals performed inside the walls.

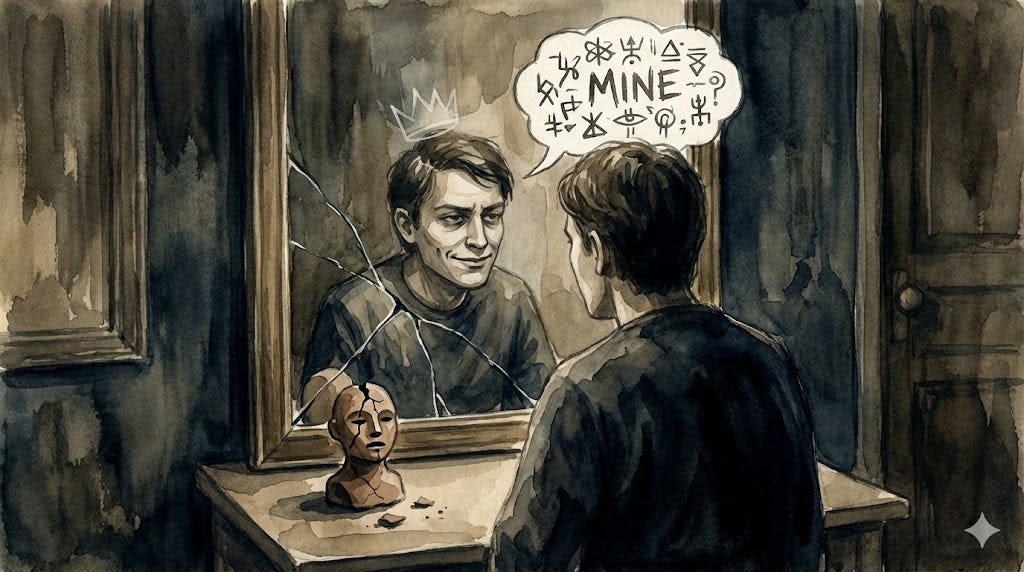

The Mother of All Idols

Now.

If the house of the self is the prison, what exactly is the lock on the door?

What is it that keeps us inside?

Imam Khomeini answers this in a phrase so concise it could fit on a ring, and so vast it could fill a library:

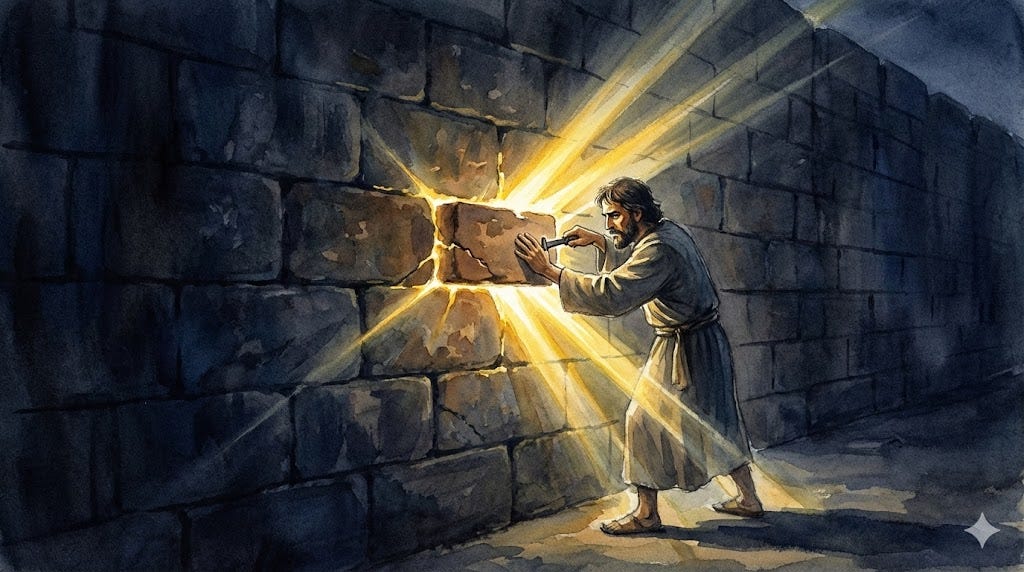

«أمُّ الاصنام صنمُ نفسك»

“The mother of all idols is the idol of your self.”

— Imam Khomeini, Adab al-Salat (The Disciplines of the Prayer), Pages 31-32

And he continues:

«إنّ حجاب رؤية النفس وعبادتها لأضخم الحجب وأظلمها، وخرق هذا الحجاب أصعب من خرق جميع الحجب، وفي نفس الحال مقدمة له، بل وخرق هذا الحجاب هو مفتاح مفاتيح الغيب والشهادة وباب أبواب العروج الى كمال الروحانية... والخروج من هذا المنزل هو أول شرط للسلوك الى الله»

“The veil of seeing the self and worshipping it is the thickest and darkest of all veils. Piercing this veil is harder than piercing all other veils, and yet it is the prerequisite for all of them. Nay, piercing this veil is the key to the keys of the Unseen and the Seen, and the door to the doors of ascent toward the perfection of spirituality. And the exit from this dwelling is the first condition for wayfaring toward God.”

— Imam Khomeini, Adab al-Salaat (The Disciplines of the Prayer), Page 31

We think of idols as things made of stone.

We think of the idol-breaking of Prophet Abraham, peace be upon him, and we picture a young man with an axe in a temple, smashing statues that cannot defend themselves.

And we admire him for it.

But what was the first idol Abraham had to confront?

Before the temple, before the axe — he had to confront his attachment to his father’s approval.

His community’s acceptance.

His own comfort and safety.

The external idols were stone.

The internal idol — the umm al-asnam, the mother of all idols — was his own nafs.

And he broke that one first.

Everything else followed.

The Staff of Moses and the Axe of Abraham

The Month of Ramadhan is the axe of Prophet Abraham.

But the idol it targets is not in a temple in ancient Babylon.

It is in your chest.

It is the “I” that demands constant feeding — feed me food, feed me attention, feed me validation, feed me outrage, feed me comfort.

The “I” that says ana — I, I, I — with every breath.

Fasting takes that “I” and, for the first time, says:

No.

Not today.

Today, you do not get what you want.

Today, I am walking out of your temple.

And there is a second prophetic parallel that deepens this further.

If the ego is an idol — and that is Prophet Abraham’s mission — it is also a Pharaoh.

And that is Prophet Moses’s mission.

Ayatullah Jawadi-Amoli, in his Hikmat-e-Ibadat (The Wisdom of Worship), makes this connection explicit:

«انسان دشمنی دارد به نام «نفس» که همواره در درون اوست... این نفس امّاره همان فرعون درون است. کار فرعون این بود که میگفت: ﴿أَنَا رَبُّکُمُ الْأَعْلی﴾. نفس امّاره نیز همین ادعا را دارد... انسان در ماه مبارک رمضان باید این فرعون را به بند بکشد.»

“Man has an enemy named the ‘Self’ — the Nafs — that is always within him. This commanding self is the inner Pharaoh. Pharaoh’s deed was to proclaim: ‘I am your Lord, the Most High.’ The commanding self makes this very same claim. In the blessed month of Ramadan, a human being must shackle this Pharaoh.”

— Ayatullah Jawad-Amoli, Hikmat-e-Ibadat (The Wisdom of Worship), Part 5: Ruzeh va Hikmat-e An (Fasting and its Wisdom)

Listen to what he is saying.

The Pharaoh is not only a figure in history.

He lives inside you.

And his declaration — the most infamous declaration in the Quran:

أَنَا۠ رَبُّكُمُ ٱلْأَعْلَىٰ

“I am your Lord, the Most High.”

— Quran, Surah al-Nazi’at (the Chapter of the Ones Who Tear Out (Violently)) #79, Verse 24

— is not only the cry of a dead tyrant in ancient Egypt.

It is the cry of the nafs ammarah, the commanding self, every single day of your life.

It says it through the craving that will not wait, the opinion that must be expressed, the comfort that cannot be sacrificed, the grudge that refuses to be released.

I am your highest priority.

Feed me.

Obey me.

Serve me first.

Every time we reach for the distraction, the snack, the phone, the sharp word — we are bowing to the Pharaoh within.

And notice Ayatullah Jawadi-Amoli’s choice of language.

He does not say that the Month of Ramadhan kills the Pharaoh.

He says it shackles him — be band bekeshad.

The Pharaoh is not destroyed in one month.

He is restrained.

He is put in chains.

And those chains are forged from hunger, from thirst, from the daily, repeated act of saying no to the most basic demands of the self.

The Month of Ramadhan is the staff of Prophet Moses cast down to swallow the serpents of the ego’s sorcery.

The fast is our la ilaha — “there is no god” — said not to statues of stone but to the tyrant that rules us from the inside.

And the illa Allah — “except The God” — is the direction of our migration.

And he takes it further still.

The Only Veil

In the same work, speaking of the inner reality of fasting, he writes:

«اگر انسان در ماه مبارک رمضان که شهرُ الله است، به لقاء الله نرسد، به باطن روزه نرسیده است؛ بلکه روزهای در سطح طبیعت گرفته است... بین ما و خدای ما چیزی نیست که حاجب باشد و نگذارد به خدا نزدیک باشیم، بلکه بین ما و خدا، خودِ ما حاجب هستیم. تمام حجابهای ما خودبینی ماست.»

“If a person does not attain the Meeting with God during the blessed month of Ramadhan — which is the Month of God — they have not reached the interior of fasting; rather, they have observed a fast only at the level of nature. There is no barrier between us and our God that prevents us from being near to Him; rather, between us and God, we ourselves are the veil. All our veils are our own self-regard.”

— Ayatullah Jawad-Amoli, Hikmat-e-Ibadat (The Wisdom of Worship), Part 5: Ruzeh va Hikmat-e An (Fasting and its Wisdom)

There is no barrier between us and God.

No wall, no locked gate, no cosmic distance.

The only thing standing between you and the Divine presence is you.

Your self-regard.

Your self-absorption.

Your insistence on being the centre of your own universe.

That is the veil.

And a fast that does not thin that veil — a fast lived only “at the level of nature,” as he puts it, a fast that is merely physical endurance — has missed its own purpose entirely.

So we have the image.

We have the house, the idol, the Pharaoh.

We have the axe of Abraham and the staff of Moses.

But a traveller needs more than a reason to leave.

A traveller needs a map.

The Map — Four Stages

And Allamah Tabatabai, in his extraordinary Lubb al-Lubab (The Innermost Essence), gives us one.

He outlines four stages of the spiritual journey that map with remarkable precision onto the experience of the Month of Ramadhan:

The First Stage — Islam Akbar, the Greater Surrender

«اسلام اکبر»

The Greater Surrender

— Allamah Sayyed Muhammad Husayn Tabatabai, Risalah Lubb al-Lubab fi Sayr wa Suluk Uli al-Albab (The Innermost Essence: On the Wayfaring and Spiritual Journey of the People of Intellect), Pages 52-54

This is the niyyah — the intention.

The moment you decide to fast.

Not the mechanical declaration before Fajr, but the real, interior decision: I am going to embark.

I am going to leave the house.

This is where every journey begins — not with the first step, but with the decision to take it.

The Second Stage — Iman Akbar, the Greater Faith

«ایمان اکبر»

The Greater Faith

— Allamah Sayyed Muhammad Husayn Tabatabai, Risalah Lubb al-Lubab fi Sayr wa Suluk Uli al-Albab (The Innermost Essence: On the Wayfaring and Spiritual Journey of the People of Intellect), Pages 52-54

This is the deepening of intention with understanding.

Not just fasting because it is obligatory, but understanding why.

Knowing what you are walking toward, not just what you are walking away from.

This is the stage where knowledge becomes fuel.

The Third Stage — Hijrat Kubra, the Greater Migration

«هجرت کبری»

The Greater Migration

— Allamah Sayyed Muhammad Husayn Tabatabai, Risalah Lubb al-Lubab fi Sayr wa Suluk Uli al-Albab (The Innermost Essence: On the Wayfaring and Spiritual Journey of the People of Intellect), Pages 52-54

This is the journey itself.

The sustained, day-after-day, hunger-after-hunger discipline of actually moving.

This is the hardest stage, because it is one thing to decide to leave and another to keep walking when the road is long and your feet are blistered and the house behind you is calling you back with every comfort you abandoned.

The Fourth Stage — Jihad Akbar, the Greater Struggle

«جهاد اکبر»

The Greater Struggle

— Allamah Sayyed Muhammad Husayn Tabatabai, Risalah Lubb al-Lubab fi Sayr wa Suluk Uli al-Albab (The Innermost Essence: On the Wayfaring and Spiritual Journey of the People of Intellect), Pages 52-54

This is the ego’s counterattack.

Because the nafs does not let you leave quietly.

It fights back — with irritability, with self-pity, with the whisper that says:

You have done enough, you can coast now, God does not expect this much of you.

This is the struggle that the Prophet, peace be upon him and his family, called the greater jihad — greater than any battle fought with swords — because the enemy is inside the walls and knows every weakness.

Tonight, we are at Stage One.

We are making the decision to embark.

Over these five sessions and thirty nights, God willing, we will move through all four stages — Surrender, Faith, Migration, Struggle.

The question is not whether the road is long.

It is whether we are willing to start walking.

The Idol Has Your Voice

And here is what I want to leave you with before we move deeper.

The idol of the self is not an abstract theological concept.

It is not something that exists only in the pages of Imam Khomeini or Allamah Tabatabai.

It is the voice you heard this morning — the one that said I deserve this.

It is the reaction you had this afternoon — the one that said I am right and they are wrong.

It is the demand you will feel tomorrow at noon — the one that says feed me, now, I cannot wait.

The idol has your voice.

The Pharaoh wears your face.

And fasting — real fasting, not the mere skipping of meals — is the first crack in that idol, the first defiance of that Pharaoh.

It is the simple, radical, world-shaking act of saying no to the most basic demand of the self: feed me.

And in that no, a door opens.

A road appears.

And the migration — the real migration, the one that matters — begins.

Movement 2: The Inward Lesson — Emptying to Be Filled

So we have established what we are leaving.

The house of the self.

The idol within.

The Pharaoh that rules from the inside.

And we have a map — four stages, from surrender to struggle.

But there is a question hanging in the air that we have not yet answered, and it is the question that will determine whether anyone in this room actually walks the road or merely admires it from a distance.

The question is: why?

Why should I leave the house of the self?

What is out there that is better than what is in here?

Because let us be honest — the house of the self is comfortable.

The patterns are familiar.

The habits are warm.

The ego’s demands are predictable and, in their own way, satisfying.

We know this house.

We have lived in it our entire lives.

And now a scholar from the thirteenth century and an imam from the twentieth are telling us to walk out into the cold and start migrating.

The Reasonable Question

The reasonable question is:

toward what?

Allamah Tabatabai answers this with a passage from his Lubb al-Lubab (The Innermost Essence) that is among the most psychologically precise things I have ever read in the mystical tradition.

He describes what happens when the wayfarer — the salik — reaches a certain stage of self-awareness.

And what happens is not enlightenment.

It is shock:

«پس از طی این مرحله تازه سالک متوجه خواهد شد که علاقۀ مفرطی به ذات خود دارد و نفس خود را تا سر حد عشق دوست دارد. هرچه بجا میآورد و هر مجاهده که میکند همه و همه ناشی از فرط حب به ذات خود است؛ زیرا که یکی از خصوصیّات انسان آنست که فطرةً خودخواه بوده، حب به ذات خود دارد. همه چیز را فدای ذات خود مینماید و برای بقای وجود خود، از بین بردن و نابود نمودن هیچ چیز دریغ نمیکند. از بین بردن این غریزه بسیار صعب و مبارزه با این حس خودخواهی از اشکل مشاکل است — و تا این حس از بین نرود و این غریزه نمیرد نور خدا در دل تجلی نمیکند، و به عبارت دیگر تا سالک از خود نگذرد به خدا نمیپیوندد.»

“Only after traversing this stage does the traveller newly realise that he has an excessive attachment to his own self, and that he loves his own soul to the point of adoration. Everything he performs, every spiritual struggle he undertakes — all of it, without exception, arises from the excess of love for his own essence. For one of the characteristics of the human being is that he is by nature self-loving; he possesses love for his own self. He sacrifices everything for his own essence, and for the preservation of his own existence he does not hesitate to destroy and annihilate anything. Eradicating this instinct is exceedingly difficult, and the battle against this sense of self-love is the most difficult of all difficulties — and so long as this sense is not eliminated and this instinct does not die, the light of God will not manifest in the heart. In other words: until the traveller passes beyond himself, he will not reach God.”

— Allamah Tabatabai, Risalah Lubb al-Lubab fi Sayr wa Suluk Uli al-Albaab (The Innermost Essense), Page 51

I want us to sit with the honesty of this passage.

Allamah is not describing the self-love of the irreligious, the careless, the person who has not yet started the journey.

He is describing the self-love of the wayfarer — the person who is already praying, already fasting, already striving.

And he says: even your striving is contaminated.

Even your spiritual struggle is, at its root, an expression of love for yourself.

You fast — but you fast because you want paradise for yourself.

You pray — but you pray because you want closeness for yourself.

You weep in du’a — but the tears are for your salvation, your forgiveness, your arrival.

The self has infiltrated even your worship.

It has disguised itself in the clothes of piety and walked right into the mosque with you.

And Allamah calls this self-love what it is.

Elsewhere in the same passage, he uses a term that should stop us in our tracks: صنم درونی — sanam-e daruni — the inner idol.

Not the idol of stone that Abraham smashed.

Not the Pharaoh that Moses confronted.

An idol so deeply embedded within us that we worship it without knowing we are worshipping it.

An idol that wears the face of devotion.

An idol that prays.

The Inner Idol That Prays

This is a devastating diagnosis.

But notice what comes at the end of the passage — and this is the key to everything:

“So long as this instinct does not die, the light of God will not manifest in the heart.”

The word is tajalli — manifestation, radiance, the breaking-through of divine light.

Allamah Tabatabai is not saying that God is absent.

He is saying that God is present — always present, always radiating — but the heart is so full of self that there is no room for the light to enter.

The vessel is occupied.

Every corner is taken up with “I” — I want, I need, I deserve, I am right.

There is simply no space left for anything else.

And this is where fasting reveals its genius.

Because fasting is, at its most fundamental level, an act of emptying.

You empty the stomach, yes — but the stomach is only the outermost shell.

What you are really emptying, if you do it properly, is the heart.

The Nutcracker and the Light

You are creating space.

You are clearing a room that has been cluttered with the furniture of the self for as long as you can remember.

And you are clearing it not because the furniture is worthless, but because something infinitely more valuable needs the space.

This brings us to the mechanism — the how.

If the diagnosis is self-love and the prescription is emptying, what is the active ingredient?

How does the fast actually work on the soul?

Imam Khomeini, in his Adab as-Salat (The Disciplines of the Prayer), gives us the answer in a single concept: kasr — breaking.

«وينبغي أن يعلم أن الإنسان ما دام في حجاب النفس والطبيعة ومحتجباً بحجب الظلمانية... فلا يتمكن من الورود في حضرة القدس الربوبية... وكسر هذه الحجب يحصل بالرياضات الشرعية والمجاهدات القلبية»

“It should be known that as long as a human being remains within the veil of the self and of nature, shrouded by veils of darkness, he cannot enter the sacred presence of the Lord. The breaking of these veils is achieved through the disciplines prescribed by the Shari’ah and the struggles of the heart.”

-- Imam Khomeini, Adab al-Salat (The Disciplines of the Prayer), Pages 39-40

The ego’s demands — particularly appetite — anchor the soul in the material realm.

They are chains.

Not metaphorical chains — functional ones.

Every time the body says feed me and you obey without thought, a link in the chain is reinforced.

Every time the ego says comfort me and you comply, the walls of the house get thicker.

Fasting breaks these chains.

It does not do so gently.

It does so through kasr — through the cracking, the fracturing, the breaking-open of the shell of the self.

And here is the paradox that sits at the heart of the entire tradition: this breaking is not destruction.

It is liberation.

Think of a walnut.

The kernel inside is nutritious, beautiful, perfectly designed — but it is locked inside a hard shell.

You cannot reach it without cracking the shell.

If you were the kernel, and someone came at you with a nutcracker, you might think you were being attacked.

You might think: they are destroying me.

But they are not destroying you.

They are freeing you.

They are breaking the thing that imprisons you so that what is inside — the real you, the luminous you, the you that was made for God — can finally emerge.

Fasting is the nutcracker.

The shell is the ego.

And what floods in through the cracks is not weakness, not emptiness, not the grim satisfaction of having endured.

What floods in is light.

This is the reframe that I want you to carry with you for the rest of this month.

We spend the Month of Ramadhan thinking about what we are giving up.

Food.

Coffee.

Cigarettes.

Comfort.

Sleep.

We frame the month in the language of loss: I can’t eat, I can’t drink, I have to wake up early.

But the tradition is telling us something radical: you are not losing anything.

You are evacuating a house so the King can enter.

You do not empty a room because you hate the furniture.

You empty it because something better is coming.

The emptiness of the stomach is not the point — it is the means.

The point is the fullness of the heart.

And there is a dimension to this emptying that deepens everything we have said so far — a dimension that makes fasting unique among all acts of worship.

The Hidden Act

Ayatollah Jawadi-Amoli identifies it in his Hikmat-e Ibadat (The Wisdom of Worship):

«روزه از جمله عبادتی است که صرفا برای خداوند است... روزه مخفی است و خدا متعال به تنهایی علم دارد... روزه یعنی رابطه خصوصی میان بنده و رب»

“Fasting is among those acts of worship that are purely for God. Fasting is hidden — and only God the Most High knows of it. Fasting means a private relationship between servant and Lord.”

— Ayatullah Jawadi-Amoli, Hikmat-e Ibadat (The Wisdom of Worship), Pages 100-102

Think about what he is saying.

Every other act of worship has an external, visible dimension.

Prayer can be seen — you stand, you bow, you prostrate, and anyone watching knows what you are doing.

Charity can be counted — the money leaves your hand and arrives in someone else’s, and there is a transaction, a receipt, a thank-you.

Pilgrimage can be photographed — the white ihram, the tawaf, the selfie at the Ka’bah.

But fasting?

Fasting is invisible.

You could be sitting at your desk right now, in a room full of people, and not a single one of them would know you are fasting.

There is no outward sign.

There is no performance.

There is nothing for the ego to display.

And this is precisely why fasting is the most lethal weapon against the inner idol.

Because the idol’s favourite fuel is recognition.

The nafs does not merely want to be fed — it wants to be seen being fed.

It wants the audience.

It wants the applause.

It wants someone to say:

Masha Allah, you are fasting?

How pious.

But fasting, by its nature, denies the nafs this fuel.

The ego cannot parade a fast.

It cannot collect compliments for an act that no one can see.

In the silence of the fast, the ego is starved of something far more essential to it than food: it is starved of attention.

This is why the Hadith Qudsi says what it says — and I want us to hear it now with new ears, after everything we have discussed:

«الصَّوْمُ لِي وَأَنَا أُجْزِي بِهِ»

“Fasting is for Me, and I am its reward.”

— Al-Tusi, Tahdhib al-Ahkaam (The Refinement of the Rulings), Volume 4, Page 152

— Al-Saduq, Man La Yahduruhu al-Faqih (For Those In Whose Presence There is No Jurist), Volume 2, Page 75

— Al-Bukhari, Sahih, Hadeeth 1904 (and 5927)

— Al-Nayshabouri, Sahih Muslim, Hadeeth 1151

Every other act of worship, God rewards through something — through paradise, through forgiveness, through blessings, through answered prayers. But fasting — because it is hidden, because it is secret, because the ego gets nothing from it — fasting God claims for Himself.

Li — for Me.

Not for your reputation.

Not for your spiritual résumé.

Not for the social credit of being seen to be pious.

For Me.

And then the second half, which Ayatullah Jawadi-Amoli reads with a precision that changes everything.

The standard reading is wa ana ajzi bihi — “and I reward for it.”

God gives you a reward.

Fine.

But the alternative reading — the one Ayatullah Jawadi prefers — is wa ana ujza bihi — “and I am its reward.”

Not paradise.

Not forgiveness.

Not blessings.

God Himself.

The reward of the fast is not something God gives you.

It is God.

The One who asked you to empty the vessel is the One who fills it.

The One who asked you to leave the house is the One waiting outside.

This is the joy that names our series.

The joy of fasting is not the iftar table.

It is the arrival at a station where the reward is the Beloved Himself.

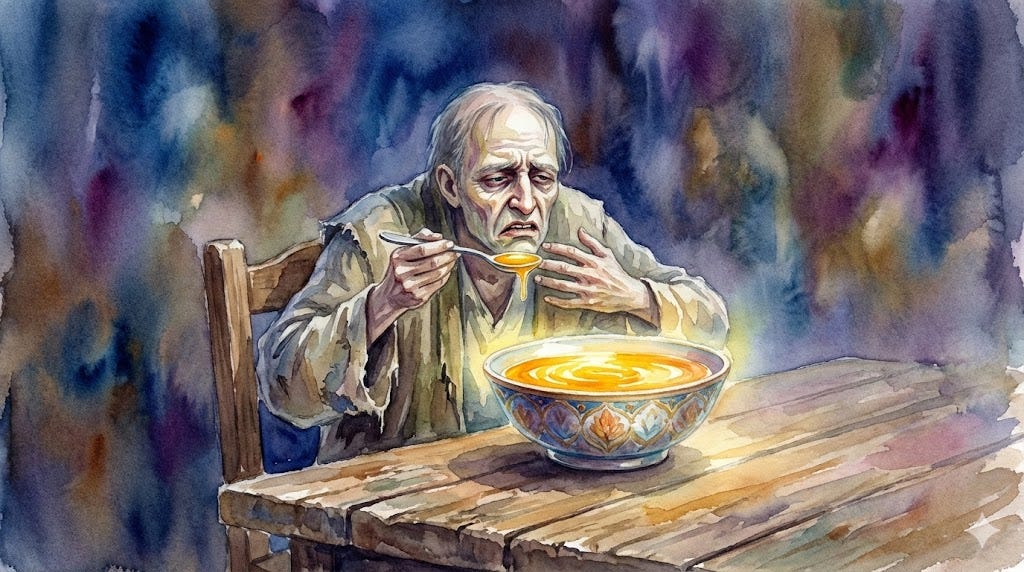

But now — and this is where I need to be honest with you, because honesty is owed — if all of this is true, if the sweetness is real and God Himself is the reward, then why don’t we feel it?

The Sick Tongue and the Honey

Why do most of us go through the Month of Ramadhan feeling hungry and tired and irritable, and not feeling this radiant, luminous joy that the scholars describe?

Is the sweetness reserved for saints?

Is it theoretical — beautiful in the books but absent from our lives?

Ayatullah Bahjat — and this is a man who spent decades in worship so intense that his students described his prayer as breathing, not ritual — gives us the diagnosis.

And it is as simple as it is devastating:

«ما مریضیم و الا باید از تلاوت قرآن و مناجات لذت ببریم. اگر مزاج انسان سالم باشد، از غذای لذیذ لذت میبرد؛ اما اگر مریض باشد، حتی عسل هم در کامش تلخ است. لذت بردن از نماز و عبادت، مشروط به این است که انسان گناه نکند. گناه، ذائقه روح را خراب میکند.»

“We are spiritually sick; otherwise, we would derive immense pleasure from reciting the Quran and intimate supplication. If a person’s constitution is healthy, they enjoy delicious food; but if they are sick, even honey tastes bitter in their mouth. Experiencing pleasure in prayer and worship is conditional upon abstaining from sin. Sin corrupts the taste buds of the soul.”

— Muhammad Husayn Rokhshad, Dar Mazar-e Bahjat (In the Presence of Bahjat), Volume 1, Page 30

The sweetness is there.

It has always been there.

The honey is on the table.

But our spiritual taste buds are sick.

The tongue of the soul is coated with a film of sin — not necessarily the dramatic sins, the ones we immediately recognise, but the accumulated residue of a thousand small surrenders to the ego: the backbiting we did not resist, the prayer we rushed through, the moment of someone’s pain we scrolled past, the gratitude we forgot to feel.

Each one, a thin layer of grime on the tongue of the heart.

And after years of accumulation, honey tastes bitter.

The Quran sounds like noise.

Du’a feels like talking to a wall.

Not because the honey changed.

Not because the Quran lost its power.

Not because God stopped listening.

Because we are sick.

And listen to how perfectly this converges with what Imam Khomeini writes in his chapter on the Presence of the Heart — Hadhur al-Qalb:

«إن قلوبنا المسكينة محرومة من حلاوة ذكر الحق... لأن قلوبنا عليلة ومريضة»

“Our poor hearts are deprived of the sweetness of the remembrance of God — because our hearts are sick and ailing.”

-- Imam Khomeini, Adab al-Salat (the Disciplines of the Prayer), Pages 71-76

Two masters.

The same word: maridh — مریض — sick.

The same diagnosis: the sweetness is real, but we cannot taste it because something is wrong with us, not with the worship.

And Ayatullah Bahjat does not leave us in the despair of the diagnosis.

He tells us what the sweetness actually is — what it feels like when the sickness lifts, when the taste buds heal, when the tongue of the heart can finally do its work:

«اگر سلاطین عالم میدانستند که انسان در حال عبادت چه لذتهایی میبرد، هرگز دنبال این مسائل مادی نمیرفتند... این لذت، با هیچ لذت مادی قابل مقایسه نیست.»

“If the kings of the world knew what pleasures a human being experiences during worship, they would never have pursued these material concerns. This pleasure is incomparable to any material delight.”

— Muhammad Husayn Rokhshad, Dar Mazar-e Bahjat (In the Presence of Bahjat), Volume 1, Page 120

If the kings of the world — the people who have access to every material pleasure, every luxury, every comfort that money and power can buy — if they knew what was available in a single prostration done with a present heart, they would abandon their thrones.

That is not the exaggeration of a poet.

That is the testimony of a man who tasted it.

Ayatullah Bahjat is not theorising.

He is reporting.

So the sweetness is real.

The sickness is real.

And the Month of Ramadhan is the cure.

The Road from Bitterness to Sweetness

But — and I must be honest with you — the cure does not work instantly.

The sickness took years to develop, and it does not lift in a single night.

Earlier tonight, I mentioned Shaykh Panahian’s map of the road ahead — bitterness, then neutral effort, then sweetness, then intimacy.

We need to return to it now, because this is the moment where theory meets the reality of your month.

Most of us, if we are honest, live our Months of Ramadhan in the first two stages.

We endure the bitterness of the early days.

We settle into the neutral rhythm of the middle.

And then the month ends before we ever taste the sweet.

The question is not whether the sweetness exists — Ayatullah Bahjat has told us it does, from personal experience.

The question is why we stop walking before we reach it.

And the answer, I think, is that we do not know what to do with the discomfort.

We feel the bitterness and assume something is wrong.

We feel the emptiness of the neutral stage and conclude that the fast is not working.

But the bitterness is the fast working.

It is the shell cracking.

It is the Pharaoh thrashing against his chains.

It is the first tremors of a building that has stood for decades beginning, finally, to give way.

The only people who never taste the sweetness are the ones who mistake the cracking for collapse — and turn back.

One Piece of Furniture

So here is what I am asking of you, practically, tonight.

Do not try to overhaul your entire soul in one evening.

The scholars would laugh at that — gently, but they would laugh.

Instead, I want you to identify one specific thing that fills your “house of the self.”

Not food — that is being handled by the fast.

Something else.

A habit of the ego.

It might be the need to have the last word in an argument.

It might be the compulsive checking of your phone — the inability to sit for five minutes without reaching for it.

It might be gossip, or self-pity, or the need for validation, or the reflex of complaint.

Name it.

Be specific.

Do not say

“I want to be a better person”

— that is too vague for the ego to fear.

Say:

“I will not check my phone during my prayer.”

Say:

I will sit in silence for five minutes after Fajr, even if it feels pointless.

And let me tell you something the scholars know that most of us do not:

the smaller the target, the more lethal the blow.

The ego is not threatened by grand resolutions.

It has seen you make them before.

It knows you will declare on the first of Ramadhan that you will transform your entire life, and it knows you will quietly abandon that declaration by the seventh.

The ego fears specificity.

It fears the person who says:

This one thing.

This one habit.

This one reaction.

I am going after this, and only this, and I will not stop.

Because when you crack one brick — truly crack it, not just paint over it — the whole wall weakens.

The ego’s power is not in any single habit.

It is in the illusion that the wall is solid, that nothing can be changed, that this is just who I am.

One cracked brick destroys that illusion.

And once the illusion breaks, the light gets in.

So be specific.

Be relentless.

And be patient — because the brick will not crack on the first night.

It may not crack on the tenth.

But if you are still pressing on the fifteenth, you will feel something shift.

And that shift is the beginning of sweetness.

Name the piece of furniture you are removing from the room.

And then, for the remaining nights of this month, remove it.

Not perfectly.

Not without relapse.

But consciously.

Every time you resist that habit, you are cracking the shell.

Every time you say no to the Pharaoh within, you are taking a step on the road.

And every step — the tradition promises — brings you closer to the sweetness that is waiting.

We must stop measuring our fast by what we abstain from and start measuring it by what we make room for.

A fast that empties the stomach but leaves the ego untouched is a renovation where the builders never arrived.

The walls are bare but nothing new has moved in.

But a fast that cracks the shell — even by a hair, even by the smallest fracture — lets in a sweetness that no iftar spread on earth can match.

Because the sweetness is not on the table.

It is in the heart.

And the heart has been waiting for this month, for this cracking, for this space, for longer than you know.

Movement 3: The Outward Call — You Have Been Invited to the Banquet of God

So we have left the house.

We have understood — at least in principle — that the idol must be broken, that the Pharaoh must be confronted, that the migration is inward before it is outward.

And we have faced the honest truth that the sweetness of arrival is real but the road is bitter before it is sweet, and that this bitterness is not punishment but medicine.

But there is a dimension we have not yet touched, and it changes everything.

Because fasting is not only a migration away from the self.

It is a migration toward something — toward Someone.

And that Someone is not waiting at the end of the road with arms folded, checking whether you have suffered enough to be admitted.

He is the One who invited you.

He is the One who prepared the banquet.

He is the One who sent the invitation before you ever thought to set out.

This is the dimension that transforms fasting from an act of discipline into an act of love.

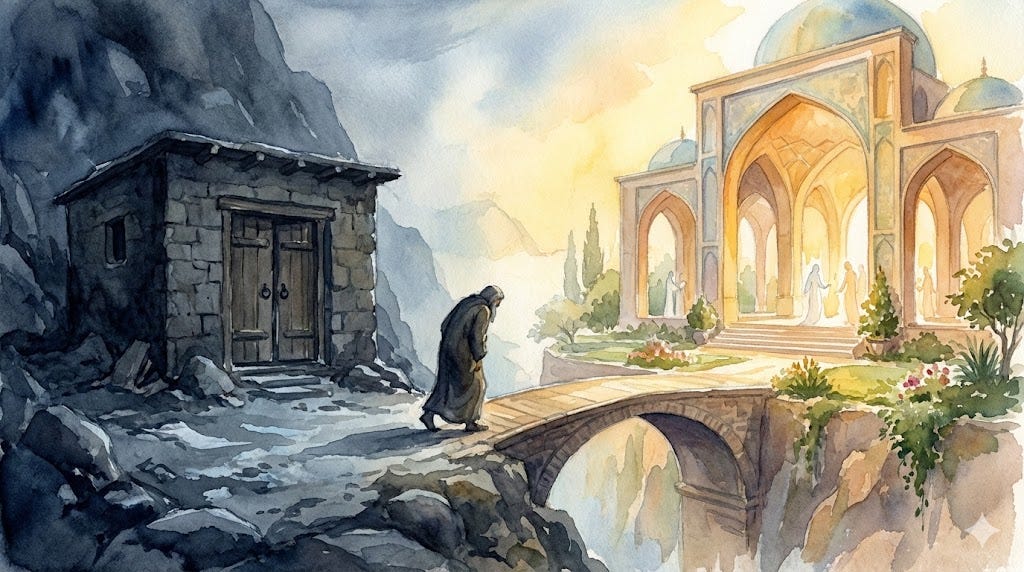

The Invitation

The Prophet Muhammad, peace be upon him and his family, delivered a sermon on the last Friday of the month of Sha’ban — the month before Ramadan — in which he announced to his community what was coming.

And the words he chose were not the language of obligation or burden.

They were the language of hospitality:

أَيُّهَا النَّاسُ إِنَّهُ قَدْ أَقْبَلَ إِلَيْكُمْ شَهْرُ اللَّهِ بِالْبَرَكَةِ وَالرَّحْمَةِ وَالْمَغْفِرَةِ، شَهْرٌ هُوَ عِنْدَ اللَّهِ أَفْضَلُ الشُّهُورِ، وَأَيَّامُهُ أَفْضَلُ الْأَيَّامِ، وَلَيَالِيهِ أَفْضَلُ اللَّيَالِي، وَسَاعَاتُهُ أَفْضَلُ السَّاعَاتِ... وَقَدْ دُعِيتُمْ فِيهِ إِلَى ضِيَافَةِ اللَّهِ

“O people, the month of God has approached you with blessing, mercy, and forgiveness — a month which, in the sight of God, is the best of months; its days the best of days; its nights the best of nights; its hours the best of hours… And you have been invited therein to the hospitality of God.”

— Mirza Jawad Maliki Tabrizi, Al-Muraqabat fi A’mal al-Sanah (Vigilant Contemplations on the Deeds of the Year), Page 235 (Khutbah al-Sha’baniyyah (The Sermon of Sha’ban), transmitted from the Commander of the Faithful, Imam Ali ibn Abi Talib (peace be upon him), from the Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him and his family)

Listen to that again:

You have been invited to the hospitality of God.

Not:

You have been commanded to fast.

Not:

You have been obligated to abstain.

You have been invited.

To a banquet.

And the Host is God.

This reframing is not incidental.

It is the key that unlocks the entire month.

The great scholar and mystic Mirza Jawad Maliki Tabrizi — whose Al-Muraqabat remains one of the most profound practical guides to spiritual wayfaring ever written — builds his entire chapter on the month of Ramadhan around this single concept: diyafat Allah, the hospitality of God.

He writes:

هذا المنزل أكرم الله فيه السائلين إليه بالدعوة إلى ضيافته، وهو دار ضيافة الله

“This station is one in which God has honoured those who turn to Him by inviting them to His hospitality — and it is the house of God’s hospitality.”

— Mirza Jawad Maliki Tabrizi, Al-Muraqabat fi A’mal al-Sanah (Vigilant Contemplations on the Deeds of the Year), Page 232

From One House to Another

Do you see the inversion?

Earlier (in Movement 1), we talked about leaving the house of the self.

Now we discover that there is another house waiting — and this one belongs to God.

The migration is not into the wilderness.

It is from one dwelling to another.

From the cramped, dark, airless house of the ego into the vast, luminous, open house of divine hospitality.

The fast is not homelessness.

It is a homecoming.

And like any banquet — like any feast hosted by a generous and noble host — this one has a dress code.

The Dress Code of the Banquet

Mirza Maliki Tabrizi does something remarkable in the pages that follow.

Having established that the Month of Ramadhan is an invitation to God’s banquet, he immediately asks the question that any sensible guest would ask:

How should I present myself?

And here the tradition gives us an answer of extraordinary practical detail.

Imam al-Sadiq, peace be upon him, transmitted the following counsel to the fasting person — and I want you to listen to this not as an ancient list of prohibitions, but as a dress code for the most important dinner invitation you will ever receive:

إِنَّ الصِّيَامَ لَيْسَ مِنَ الطَّعَامِ وَالشَّرَابِ فَقَطْ... إِذَا صُمْتَ فَلْيَصُمْ سَمْعُكَ وَبَصَرُكَ وَلِسَانُكَ وَجِلْدُكَ وَشَعْرُكَ... فَاحْفَظُوا أَلْسِنَتَكُمْ عَنِ الْكَذِبِ وَغَضُّوا أَبْصَارَكُمْ وَلَا تَنَازَعُوا وَلَا تَحَاسَدُوا وَلَا تَغْتَابُوا وَلَا تَمَارُوا وَلَا تَكْذِبُوا وَلَا تُبَاشِرُوا وَلَا تُخَالِفُوا وَلَا تَغَاضَبُوا وَلَا تَسَابُّوا وَلَا تَشَاتَمُوا وَلَا تَتَفَاتَرُوا وَلَا تَظْلَمُوا وَلَا تُنَادُوا وَلَا تُجَادِلُوا... وَلَا تَغْفُلُوا عَنْ ذِكْرِ اللَّهِ وَعَنِ الصَّلَاةِ

“Fasting is not merely from food and drink... When you fast, let your hearing fast, and your sight, and your tongue, and your skin, and even your hair... Guard your tongues from falsehood, lower your gazes, and do not quarrel, nor envy, nor backbite, nor dispute, nor lie, nor be intimate inappropriately, nor oppose one another in anger, nor insult, nor curse, nor slacken in devotion, nor oppress, nor call out in hostility, nor argue... and do not become heedless of the remembrance of God and of prayer.”

— Mirza Jawad Maliki Tabrizi, Al-Muraqabat fi A’mal al-Sanah (Vigilant Contemplations on the Deeds of the Year), Page 239-240 (Narrated from Imam al-Sadiq (peace be upon him), transmitted through al-Hasan ibn Ali ibn al-Faddal)

This is not a list of things you cannot do.

This is a description of what it looks like when someone walks into the presence of a King and behaves accordingly.

You would not walk into the palace of a generous host and then spend the evening arguing with the other guests, lying about your credentials, looking at what is not yours, and speaking ill of people behind their backs.

You would not show up to a feast smelling of the gutter.

And Mirza Maliki Tabrizi makes this point explicitly.

He writes that all states, actions, and words that distance you from the Divine Presence are contrary to the purpose of the invitation itself — and then he asks a devastating question:

وَلا تَرضى أَن تَكونَ في دارِ ضِيافَةِ هذا المَلِكِ الجَليلِ — المُنعِمِ لَكَ بِهذا التَّشريفِ وَالتَّقريبِ — العالِمِ بِسَرائِرِكَ وَخَطَراتِ قَلبِكَ — غافِلاً عَنهُ وَهُوَ مُراقِبٌ لَكَ، وَمُعرِضاً عَنهُ وَهُوَ مُقبِلٌ عَلَيكَ

“And you would not accept being in the house of the hospitality of this majestic King — the One who has bestowed upon you this honour and nearness — the One who knows your innermost secrets and the passing thoughts of your heart — heedless of Him while He watches over you, and turning away from Him while He turns toward you.”

— Mirza Jawad Maliki Tabrizi, Al-Muraqabat fi A’mal al-Sanah (Vigilant Contemplations on the Deeds of the Year), Page 239

That question should stop us in our tracks.

Because that is exactly what most of us do.

We accept the invitation — we fast, we show up — and then we spend the month scrolling through our phones during prayer, gossiping between iftar dishes, losing our tempers with our families by mid-afternoon, and treating the entire month as an endurance test rather than the most intimate encounter we will ever be offered.

We are at the banquet.

But we have come in the wrong clothes.

Honour, Not Imposition

And here is where Mirza Maliki Tabrizi delivers what I believe is the single most important reframe for anyone who has ever experienced the Month of Ramadhan as a burden.

He writes:

اعلم أنّ الصوم ليس تكليفاً بل تشريف

“Know that fasting is not an imposition (taklif) — it is an honour (tashrif).”

— Mirza Jawad Maliki Tabrizi, Al-Muraqabat fi A’mal al-Sanah (Vigilant Contemplations on the Deeds of the Year), Page 238

Taklif versus tashrif.

Imposition versus Honour.

The difference between those two words is the difference between a conscript and a guest.

A conscript is forced to serve.

A guest is invited to feast.

A conscript endures the hours.

A guest savours them.

A conscript counts down to release.

A guest dreads the moment the evening ends.

Which one are you?

Because Mirza Maliki Tabrizi goes further.

He says: once you understand that fasting is an honour and not a burden, you realise that the purpose of the fast is not to punish the body but to elevate the soul.

The hunger is not the point — it is the vehicle.

And he reminds us that the tradition teaches this explicitly:

أنّ الصوم ليس من الطعام والشراب فقط

“Fasting is not from food and drink alone.”

— Mirza Jawad Maliki Tabrizi, Al-Muraqabat fi A’mal al-Sanah (Vigilant Contemplations on the Deeds of the Year), Page 238 (citing the narration from Imam al-Sadiq)

The body’s fast is the door.

But through that door, something far deeper is happening: every organ, every sense, every faculty of the soul is being invited to participate in the migration.

Your ears fast from gossip and slander.

Your eyes fast from what degrades you.

Your tongue fasts from cruelty and falsehood.

Your heart fasts from attachment to everything that is not God.

The Three Ranks

And this brings us to a teaching that the scholars have transmitted across centuries — the three ranks of the fast.

Mirza Maliki Tabrizi presents them with characteristic clarity:

وَكَيفَ كانَ مَراتِبُ الصَّومِ ثَلاثَة: صَومُ العَوامِّ: وَهُوَ بِتَركِ الطَّعامِ وَالشَّرابِ وَالنِّساءِ — عَلى ما قَرَّرَهُ الفُقَهاءُ مِن واجِباتِهِ وَمُحَرَّماتِهِ.وَصَومُ الخَواصِّ: وَهُوَ تَركُ ذلِكَ مَعَ حِفظِ الجَوارِحِ مِن مُخالَفاتِ اللهِ عَلى الإطلاقِ.وَصَومُ خَواصِّ الخَواصِّ: وَهُوَ تَركُ كُلِّ ما هُوَ شاغِلٌ عَنِ اللهِ مِن حَلالٍ أَو حَرامٍ.

“The ranks of fasting are three: The fast of the common people (sawm al-’awam): which consists of abstaining from food, drink, and marital relations — according to what the jurists have established of its obligations and prohibitions. The fast of the elect (sawm al-khawass): which is that abstention together with the guarding of every limb from disobedience to God without exception. And the fast of the elect of the elect (sawm khawass al-khawass): which is the abandoning of everything that distracts from God — whether lawful or unlawful.”

— Mirza Jawad Maliki Tabrizi, Al-Muraqabat fi A’mal al-Sanah (Vigilant Contemplations on the Deeds of the Year), Page 241-242

Most of us live at the first rank.

And there is no shame in that — Mirza Maliki Tabrizi is clear that the first rank is valid and accepted.

But the invitation of the Month of Ramadhan is to climb.

To move from the fast of the body to the fast of the limbs to the fast of the heart.

To arrive, even if only for a single moment in the entire month — even if only for a single prostration — at the third rank, where the distance between you and God is so thin that you can almost hear His breath.

The Migration We Witness

And now I must say something that cannot wait until a later session, because if I leave it unsaid, everything we have discussed tonight becomes an abstraction, and abstractions are the luxury of the comfortable.

We are talking about migration tonight.

Spiritual migration.

The elegant, interior movement from the house of the self to the house of God.

We sit in warm rooms and discuss the metaphor of hijrah while reading scholars who wrote in libraries and study circles.

But there are people on this earth right now — at this very moment — for whom migration is not a metaphor.

In Gaza, families are migrating from one destroyed neighbourhood to another, carrying their children and whatever they could grab before the walls fell.

In Sudan, people are fleeing on foot from a war that has already killed tens of thousands.

Across the Mediterranean, in the Sahara, on the borders of a dozen countries, human beings are risking their lives in the most literal act of leaving the house that there is — because the house is burning, or bombed, or no longer standing.

And let us not make the mistake of believing that suffering lives only in war zones.

There are people in London tonight who must choose between warmth and food — in one of the wealthiest cities in human history.

There are families in New York and Toronto who ration their medication because the price of staying alive exceeds what they earn.

There are elderly people in Paris and Berlin who will spend this entire month without a single visitor, abandoned by systems that measure human worth in productivity.

There are families in Jakarta and Kuala Lumpur who work from before dawn until after dark and still cannot outpace the rising cost of feeding their children — in nations rich with resources that somehow never reach the people who need them most.

There are mothers in Nairobi and Dar es Salaam who walk hours for clean water that should flow from the tap — in lands whose minerals power the phones in our pockets.

There are young people in Lagos and Johannesburg with degrees and ambitions and no economy willing to receive them — told to be patient by the same systems that stripped their nations bare.

The oppressed are not only in the places we see on the news.

They are on the next street.

They are in the flat above yours.

They may be in this room.

And the Prophet — in that same sermon we quoted tonight — said this:

تَصَدَّقُوا عَلَى فُقَرَائِكُمْ وَمَسَاكِينِكُمْ... وَارْحَمُوا صِغَارَكُمْ... وَصِلُوا أَرْحَامَكُمْ... وَتَحَنَّنُوا عَلَى أَيْتَامِ النَّاسِ يُتَحَنَّنْ عَلَى أَيْتَامِكُمْ

“Give charity to your poor and your destitute… and show mercy to your young… and maintain your ties of kinship… and show compassion to the orphans of others, so that compassion may be shown to your orphans.”

— Mirza Jawad Maliki Tabrizi, Al-Muraqabat fi A’mal al-Sanah (Vigilant Contemplations on the Deeds of the Year), Page 253-254

Show compassion to the orphans of others.

Not the orphans of your community, your ethnicity, your nation — the orphans of others.

The Prophet is telling us that the fast is not complete until the inward migration becomes an outward one.

Until the hand that stopped reaching for food starts reaching for someone else.

Until the heart that emptied itself of ego fills with something more dangerous and more beautiful than personal piety: solidarity.

A fast that makes you kinder, more generous, more outraged at injustice — that fast has truly left the house of the self.

A fast that makes you irritable, withdrawn, and indifferent to the suffering of others — that fast never left the driveway.

So here is your practical task for tonight — not a spiritual exercise, but a human one.

Earlier tonight (in Movement 2), I asked you to name one piece of furniture in the house of the self and remove it.

That was the inward task.

This is the outward one, and it is just as important — because a migration that only turns inward eventually becomes another form of self-absorption.

Tonight, before you sleep, find one concrete way to give.

And I mean concrete.

Not “I will be more generous this month” — the ego is not afraid of that.

I mean: identify a specific person and do a specific thing.

It might be a family in your community who is struggling — and you send them money tonight. Not tomorrow. Tonight.

It might be a parent or a sibling you have not spoken to in weeks — and you pick up the phone and call them.

Not a text.

A call.

Let them hear your voice.

It might be someone you know who is alone this Ramadhan — a convert with no community, a student far from home, an elderly person whose children have stopped visiting — and you invite them to your iftar table.

You send the message tonight.

It might be that you choose one reliable organisation working in Gaza, in Sudan, in whatever broken corner of this earth pulls at your conscience — and you set up a recurring donation.

Not a one-off.

Something that outlasts your Ramadhan motivation.

And if you have nothing to give materially — and there is no shame in that — then pray.

But pray specifically.

Learn one name.

One real name of one real person in one real place who is suffering.

And say their name in your sujud tonight.

Make them real to yourself.

Let them into your du’a not as a category but as a person.

If your hunger this month does not connect you to the hunger of someone who did not choose it, the migration has stalled at the border of the self.

Let the banquet of God overflow from your table to theirs.

Conclusion and Bridge to Session 2 — The Purification of the Mirror

Tonight we talked about leaving.

About breaking the idol of the self.

About Allamah Tabatabai's four stages.

About the sweetness that awaits and the bitterness that comes first.

And about the extraordinary truth that this journey is not a march into exile but a response to an invitation — that God Himself has prepared a banquet and we are His guests.

But a traveller who leaves home does not simply arrive.

There is something between departure and arrival, and it is the thing that determines whether you reach the door fit to enter or arrive dusty, dishevelled, and still carrying the baggage you were supposed to leave behind.

That something is purification.

In the next session, God willing, we will ask: what must we cleanse so that when we arrive at God’s door, we are presentable?

The scholars call it the purification of the mirror — because the heart is a mirror, and if the mirror is covered in dust and rust and the residue of years of heedlessness, it does not matter how bright the Light shining upon it is.

The reflection will be distorted, dim, or absent altogether.

Imam Khomeini identifies three levels of purification.

Allamah Tabatabai describes the inner rust that must be scraped away.

And Mirza Maliki Tabrizi tells us that the dress code of the banquet is not just about what we refrain from — it is about what we must actively become.

That is Session 2: The Purification of the Mirror.

How to clean the heart so it can receive the Light.

But for tonight — begin the migration.

Take the first step.

Name the idol.

Feel the hunger.

And know — with the certainty of the Prophet’s own words — that you have not been abandoned on this road.

You have been invited.

A Supplication for the Migrant Heart

In the name of God, the All-Compassionate, the All-Merciful.

O God,

We come to You tonight as travellers who have only just discovered that they need to travel.

We have been sitting in the house of the self for so long that we mistook its walls for the horizon.

We thought the ceiling was the sky.

We decorated our prison and called it home.

And now — through the words of Your Prophet and the wisdom of those who walked this road before us — we hear Your voice calling us out.

Calling us to leave.

Calling us toward You.

O Lord, we confess: the idol is not outside us.

It is us.

It wears our face and speaks with our voice.

It has been with us so long that we cannot always tell where it ends and we begin.

We ask You — by the light of this blessed month that is approaching — to help us see the difference.

To help us break what must be broken.

To help us leave what must be left.

O God, You who declared “Fasting is for Me, and I am its reward” — we ask You to be our reward.

Not the gardens, though we long for them.

Not safety from the fire, though we fear it.

You.

Let us fast for You, and let the reward be nearness to You, and let that nearness be the sweetness that the masters describe — the sweetness that makes kings envious and makes the whole world seem small.

O Lord, our hearts are sick.

We know this now.

The honey is there but we cannot taste it.

The banquet is set but we have come in the wrong clothes.

We ask You — by Your mercy that encompasses all things — to heal us.

Not all at once, for we are not yet ready to receive them.

But one degree at a time.

One prayer at a time.

One moment of presence at a time.

Cure us slowly, Lord, for we have been sick a long while.

O God, we remember tonight those for whom migration is not a metaphor.

Those who left their homes not in search of You but in flight from bombs and bullets and starvation.

The mothers carrying children through rubble.

The fathers who can no longer protect.

The orphans of Gaza, of Sudan, of Syria, ofLebanon, of every broken place on this earth that You created beautiful and that we have defaced with our cruelty.

O Lord, show compassion to the orphans of others — Your Prophet taught us this.

And we ask You: let our fast be for them too.

Let the hunger we choose remind us of the hunger they did not choose.

Let our voluntary thirst be a prayer for those who thirst because there is nothing left to drink.

O Lord, You are the One who invited us.

You prepared the banquet before we knew we were hungry.

You lit the road before we knew we were lost.

You called us guests when we deserved to be called fugitives.

What generosity is this?

What host prepares a feast for those who spent the year ignoring His existence?

Only You.

Only You.

O God, we set out tonight.

The road is long and our legs are weak and the Pharaoh in our chest will not go quietly.

But we have heard the invitation.

We have heard the Prophet say, “You have been invited to the hospitality of God.”

And we respond.

We accept.

We leave the house.

Receive us, O Lord.

Receive us as we are — broken, confused, half-asleep, still carrying baggage we should have dropped years ago.

Receive us, and do not turn us away.

For if You turn us away, where else would we go?

There is no other door.

There is no other Host.

There is no one else.

O Lord of the worlds, we ask You — by Muhammad and the family of Muhammad, by the tears of Zaynab and the blood of Husayn, by the patience of the Awaited One who watches from behind the veil of the unseen — hasten the arrival.

The collective arrival.

The day when the migration is complete, when justice replaces tyranny, when the oppressed are freed, and when the whole earth becomes what the Month of Ramadhan tries to make of a single heart: a place where God is remembered, and where no one is forgotten.

Amen, O Lord Sustainer of the Universes.

Amen, O Most Merciful of the Merciful.

And from Him alone is all ability and He has authority over all things.