[20] The Art of Supplication - The Sacred Windows: The Role of Place - Part 5 - The Hearth, The Hub, and The Horizon

A series of discussions based on the book Uddat al-Dai wa Najah as-Saee - The Provision of the Supplicant, and the Triumph of the Seeker by Ibn Fahd al-Hilli on the subject of Supplication and Prayer.

In His Name, the Most High

This is the twentieth part of our series, The Art of Supplication, an ongoing exploration into the sacred relationship between the supplicant, the supplication, and the Divine.

The insights within this series are cumulative, and the nature of our discussion requires that each part build upon foundations laid in the ones that came before.

To prevent any misunderstanding and to fully benefit from the depth of this subject, it is essential that you engage with the previous parts in order before continuing with this one.

The previous parts in this series can be found here:

Video of the Majlis (Sermon/Lecture)

This write up is a companion to the video majlis (sermon/lecture) found below:

Audio of the Majlis (Sermon/Lecture)

This write up is a companion to the audio majlis (sermon/lecture) found below:

Recap

The Sacred Windows: The Prison, The Portal, and The Presence

In our last session, our journey through the sacred windows of place took us to the thresholds of concealment and the geography of continuity, where we learned the profound lessons of endurance, anticipation, and the dispersed presence of the Ahl al-Bayt.

Our path began in Kadhimiyyah, which we called the Prison of imprisoned light. There, in the steadfastness of Imam al-Kadhim, we learned that true power is not worldly authority but spiritual endurance.

We were also confronted with a painful mirror: the test of a community that was busy with the rituals of mourning a martyred Imam while neglecting its duty to the living Imam languishing in a dungeon.

We then traveled to Samarra, the Portal to the unseen.

At the doorstep of the Great Occultation, under the watchful eyes of the tyrants, we learned that the veiling of the Imam was not a rupture but a divine plan.

We clarified that the duty of waiting (intidhar) is not one of passive hope, but of active, revolutionary preparation for his return.

Finally, we traced the Presence of the Ahl al-Bayt across the globe through the dispersed lamps of the Imamzadehs.

From the shrines of Syria and Iran to the blessed graves in Pakistan, Morocco, and Yemen, and through the legacy of the Hadhrami Sayyids in Southeast Asia, we saw how the barakah of Wilayah was planted across the horizons, ensuring no community is left without a tangible connection to the Prophet’s family.

But what is the ultimate purpose of this vast, global map of sacred ground?

The school of the Ahl al-Bayt teaches that we visit these external “signs on the horizons” to learn how to cultivate the “signs within ourselves.”

Tonight, in our final session on the Role of Place, we bring this entire journey home...

The Role of Place - Part 5 - The Hearth, The Hub, and The Horizon

The Local Mosque — The Beating Heart

From the great peaks of global sanctity, our journey now descends into the valleys where our daily lives unfold.

We bring the lessons of the grand sanctuaries home, to the most important sacred space in our local community: the mosque.

The local mosque is the beating heart of the community, a sanctuary not just for prayer, but for remembrance, education, and the protection of the vulnerable.

It is the first and most vital “mini-Qom” or “mini-Najaf” we must build. The Qur’an itself designates these as places of profound significance:

فِى بُيُوتٍ أَذِنَ ٱللَّهُ أَن تُرْفَعَ وَيُذْكَرَ فِيهَا ٱسْمُهُۥ يُسَبِّحُ لَهُۥ فِيهَا بِٱلْغُدُوِّ وَٱلْـَٔاصَالِ

“[This light is] in houses which God has permitted to be raised and His name to be remembered therein; exalting Him within them in the morning and the evenings.”

— Qur’an, Surah al-Nur (the Chapter of the Light) #24, Verse 36

The commentators explain that the phrase “permitted to be raised” (an turfa‘a) refers not only to physical construction, but more importantly, to the elevation of their spiritual rank and honour. The traditions of the Ahl al-Bayt identify the ultimate and most perfect examples of these divinely-honoured “houses.”

عَنْ أَنَسِ بْنِ مَالِكٍ وَبُرَيْدَةَ قَالَا: قَرَأَ رَسُولُ اللَّهِ صَلَّى اللَّهُ عَلَيْهِ وَآلِهِ وَسَلَّمَ هَذِهِ الْآيَةَ {فِي بُيُوتٍ أَذِنَ اللَّهُ أَنْ تُرْفَعَ وَيُذْكَرَ فِيهَا اسْمُهُ}، فَقَامَ إِلَيْهِ رَجُلٌ فَقَالَ: أَيُّ بُيُوتٍ هَذِهِ يَا رَسُولَ اللَّهِ؟ قَالَ: بُيُوتُ الْأَنْبِيَاءِ. فَقَامَ إِلَيْهِ أَبُو بَكْرٍ فَقَالَ: يَا رَسُولَ اللَّهِ، هَذَا الْبَيْتُ مِنْهَا؟ - لبيت علي وفاطمة - قَالَ: نَعَمْ، مِنْ أَفَاضِلِهَا.

It is narrated from Anas ibn Malik and Buraydah that the Messenger of God (peace be upon him and his family) recited this verse: {In houses which God has permitted to be raised and His name to be remembered therein}.

A man stood up and asked, “Which houses are these, O Messenger of God?”

He replied, “The houses of the Prophets.”

Then Abu Bakr stood up and asked, “O Messenger of God, is this house one of them?”—pointing to the house of Ali and Fatimah.

He replied, “Yes, and it is among the most excellent of them.”

— This narration is widely cited. See: Al-Suyuti, Tafsir al-Durr al-Manthur, Volume 6, Page 203 (commentary on Surah al-Nur, 24:36); Al-Tha’labi, Tafsir al-Kashf wal-Bayan; Al-Alusi, Ruh al-Ma’ani

This profound narration teaches us a crucial lesson: the archetype for every local mosque, every house of God, is the very home of the Ahl al-Bayt.

Our mosques are meant to be a reflection, however humble, of that original sanctuary of purity, divine light, and unwavering remembrance of God.

The House of God: A Sanctuary for All

The first and most crucial principle of the mosque is that it belongs to God alone. It is not the property of a family, a tribe, a donor, or a specific ethnic group. All rivalries and claims of personal ownership are invalid and a betrayal of the mosque’s sacred purpose. God states this unequivocally:

وَأَنَّ ٱلْمَسَـٰجِدَ لِلَّهِ فَلَا تَدْعُوا۟ مَعَ ٱللَّهِ أَحَدًا

“And [He revealed] that the mosques are for Allah, so do not invoke with Allah anyone.”

— Qur’an, Surah al-Jinn (the Chapter of the Jinn) #72, Verse 18

Because it is God’s house, it must be the most welcoming of places. The Prophet (peace be upon him and his family) declared:

أَحَبُّ الْبِلَادِ إِلَى اللَّهِ مَسَاجِدُهَا

“The most beloved of places to Allah are their mosques.”

— This is a famous prophetic narration. Its most well-known transmission is found in the Sunni canon in Sahih Muslim, Kitab al-Masajid (The Book of Mosques), Hadith #671. The principle is powerfully corroborated in Shia sources, where the mosques are referred to as ‘the houses of God on Earth’ (بيوت الله في الأرض), a title established in numerous narrations, including in Shaykh al-Saduq’s Man La Yahduruhu al-Faqih, Volume 1, Page 238

It is a sanctuary for all believers, a microcosm of the divine order where all stand equal before their Lord. The maraji’ have consistently upheld this principle. The late Grand Ayatullah Sayyed Abu al-Qasim al-Khoei was often asked about preventing certain believers from entering a mosque due to disputes, and his ruling was firm:

لا يجوز منع أي مسلم من الدخول في المساجد و المراكز الإسلامية للصلاة و العبادة و سائر الإستفادات الدينية المشروعة

“It is not permissible to prevent any Muslim from entering mosques and Islamic centres for prayer, worship, and other legitimate religious benefits.”

— Ayatullah al-Udhma Sayyed Abu al-Qasim al-Khoei, Sirat al-Najat (The Path of Salvation), Volume 2, Question #1229

This ruling is not merely a matter of social etiquette; it is a foundational principle that was tragically violated during the recent global pandemic.

In that time of great confusion and fear, many mosques and centres—often acting out of a misguided sense of civic duty—closed their doors to some of the most vulnerable members of our community.

The elderly and the infirm, who for legitimate health or personal reasons were unable to take certain medical interventions, were in some cases barred from entering the House of God.

This act of exclusion compounded their isolation, broke their hearts, and in some tragic instances, may have hastened their departure from this world.

This is a profound and unacceptable tragedy.

Those who took it upon themselves to prevent believers from entering God’s own sanctuary—regardless of the pretext—must confront the severe warning given in the Qur’an itself:

وَمَنْ أَظْلَمُ مِمَّن مَّنَعَ مَسَاجِدَ اللَّهِ أَن يُذْكَرَ فِيهَا اسْمُهُ وَسَعَىٰ فِي خَرَابِهَا

“And who are more unjust than those who prevent the name of Allah from being mentioned in His mosques and strive toward their ruin?”

— Qur’an, Surah al-Baqarah (the Chapter of the Cow) #2, Verse 114

The great exegetes of the Qur’an have explained that the “ruin” (kharab) mentioned in this verse is not merely physical demolition.

The true life of a mosque is the remembrance of God within it.

Therefore, any act that prevents this remembrance is an act of “ruining” the mosque.

Allamah Tabatabai explains in his monumental tafsir, Al-Mizan:

والمراد بخرابها تعطيلها وإبطال العبادة فيها، فإن عمارة المسجد ليست بمجرد تشييد بنائه، بل بأن يذكر فيها اسم الله. فمنع العبادة فيه هو السعي في خرابه.

“What is meant by their ‘ruin’ is to render them inactive and to nullify worship within them. For the flourishing (‘imarah) of a mosque is not merely in the construction of its building, but in the remembrance of God’s name within it. Therefore, to prevent worship in it is to strive toward its ruin.”

— Allamah Sayyed Muhammad Husayn Tabatabai, Tafsir al-Mizan, Volume 1, Commentary on Surah al-Baqarah (2), Verse 114, Page 259

Building on this, the great contemporary philosopher and jurist, Ayatullah Jawadi-Amoli, explains that a mosque has a body and a soul.

To bar worshippers is to kill its soul:

مسجد یک کالبد و یک روح دارد. روح مسجد همان ذکر و عبادت است. کسی که مانع ذکر خدا در مسجد شود، در حقیقت روح مسجد را از آن گرفته و آن را به یک ساختمان بیجان تبدیل کرده است. این بزرگترین تخریب است.

“A mosque has a body and a soul. The soul of the mosque is remembrance (dhikr) and worship. One who prevents the remembrance of God in the mosque has, in reality, taken the soul from it and turned it into a lifeless building. This is the greatest form of destruction.”

— Ayatullah Abdollah Jawadi-Amoli, from his commentary series Tafsir Tasnim, Volume 6, Commentary on Surah al-Baqarah (2), Verse 114

Therefore, according to this profound understanding, to bar a believer from the mosque is to participate in its spiritual ruin. While the maraji’ advised believers to follow the trustworthy advice of independent and credible medical experts for their own safety, they never sanctioned the act of forcefully barring a Muslim from prayer.

The rulings of Ayatullah al-Udhma Sayyed Ali al-Sistani during that period consistently emphasised personal responsibility and the following of independent expert medical counsel, but never delegated authority to mosque committees to enforce mandates by exclusion.

This act violates the very sanctity of the believer (hurmat al-mu’min), a principle so foundational that the Imams have taught it is greater than the sanctity of the Ka’bah itself.

Imam Ja’far al-Sadiq (peace be upon him) looked at the Ka’bah and declared:

مَا أَعْظَمَ حُرْمَتَكِ! وَاللَّهِ إِنَّ حُرْمَةَ الْمُؤْمِنِ أَعْظَمُ مِنْ حُرْمَتِكِ

“How great is your sanctity! By God, the sanctity of the believer is greater than your sanctity.”

— Al-Majlisi, Bihar al-Anwar, Volume 64, Page 71

To break a believer’s heart by turning them away from the House of God is a transgression of immense proportions.

The history of the Ahl al-Bayt is one of radical inclusion.

The Prophet (peace be upon him and his family) welcomed the poor, the destitute, and even the “sinner” into his mosque.

There is no precedent in our tradition for creating a two-tiered community where some are deemed “unclean” or “unsafe” to enter the houses of God.

Those who participated in such exclusion have a heavy weight to bear, and it would not be an exaggeration to say that, in the light of these principles, they have blood on their hands.

The Prophetic Model: A Microcosm of a Divine Society

The mosque of the Prophet in Madinah was not merely a prayer hall.

It was the nucleus of the entire community: a place of governance, a court of law, a school for education, and a shelter for the poor (Ahl al-Suffa).

The modern mosque is called to be the inheritor of this holistic model, a hub for both spiritual and social life, led by qualified and pious leadership.

This “mini-Wilayah” system requires a genuine scholar from the Hawza to set the ideological and theological direction, ensuring that the pulpit is a source of authentic knowledge, not personal opinion or divisive rhetoric.

This leadership must then guide the community towards the highest ethical standard: selfless service.

When the Ahl al-Bayt gave their food to the needy, the orphan, and the captive, they set the eternal standard for all community service, a standard immortalised in the Qur’an:

إِنَّمَا نُطْعِمُكُمْ لِوَجْهِ ٱللَّهِ لَا نُرِيدُ مِنكُمْ جَزَآءً وَلَا شُكُورًا

“[Saying], ‘We feed you only for the countenance of God. We wish not from you reward or gratitude.’”

— Qur’an, Surah al-Insan (the Chapter of the Man) #76, Verse 9

When our mosques distribute food, this is the model. The same meal served inside should be quietly sent to the neighbours, the local homeless shelters, and soup kitchens—not for advertisement, but purely for the sake of God’s countenance.

A Crucial Clarification for the Diaspora: The Sigheh of Masjid

For communities in the diaspora, particularly in the West, there is a crucial point of jurisprudence (fiqh) that is often misunderstood. In Islamic law, for a property to be formally and irrevocably designated as a masjid (mosque), a specific verbal formula of endowment (waqf), known as the sigheh-ye masjid (the contract of the masjid), must be recited.

Once this formula is recited with the correct intention, the land and building are removed from private ownership and belong to God in perpetuity. This means the property can never be sold, inherited, or repurposed for any other function, forever.

This creates a legal distinction between a formal, endowed masjid and a prayer hall, often called a musalla or an Islamic Centre, where the sigheh has not been recited.

It is vital to understand that this is a legal distinction, not necessarily a spiritual one.

A vibrant musalla filled with worship and community service is far more beloved to God than an empty, formal masjid.

The distinction is about legal permanence and flexibility.

It is precisely because of this permanent, irreversible status that the senior maraji’ have warned that reciting the sigheh can be deeply problematic for diaspora communities.

A community may outgrow its building and need to move. The demographics of a neighborhood may change, making the location impractical or even unsafe.

If the sigheh has been recited, the community is trapped with a building they cannot sell to fund a new, better one.

For this reason, the guidance from the highest authorities is to be extremely cautious.

Ayatullah al-Udhma Sayyed Ali al-Sistani gives the following clear ruling - and all the contemporary historic maraje’ have the virtually the same position:

لا ينبغي التسرّع في وقفه مسجداً بل يبقى على ملك بانيه أو ملك الجهة التي اشترته ما لم تقتض المصلحة الملزمة وقفه مسجداً، ويكتفى بإقامة الصلاة فيه و سائر النشاطات الدينية لكي لا تترتب عليه الأحكام الشرعية للمسجدية التي قد تخلق بعض الصعوبات في المستقبل

“One should not rush into endowing it as a mosque. Rather, it should remain the property of its builder or the entity that bought it, as long as a binding interest does not necessitate its endowment as a mosque. It is sufficient to establish prayer and other religious activities in it, so that the legal rulings of masjidiyyah—which may create some difficulties in the future—do not apply to it.”

— Ayatullah al-Udhma Sayyed Ali al-Sistani, Fiqh lil-Mughtaribin (Jurisprudence for Those Abroad), Ruling #375

The wise approach, therefore, is to establish an “Islamic Centre” or “Prayer Hall” (musalla) held in a trust. This allows for all the functions of a mosque while preserving the crucial flexibility for the community to grow and adapt to future circumstances.

Calls to Clarify: The Adab (Etiquette) of God’s House

To honour the mosque is to make it a living sanctuary that reflects the justice and mercy of its true Owner.

Clarify Our Ownership: From a Private Club to God’s House

We must actively resist the temptation of factionalism, be it based on family, ethnicity, or financial contribution. The mosque belongs to God, and it must be open and welcoming to all of His servants.

This requires a conscious effort to dismantle cliques, welcome newcomers, and ensure that the administration serves the entire community, not just a select few.

Clarify Our Purpose: From a Ritual Space to a Community Hub

We are called to revive the full prophetic function of the mosque. This means ensuring it is not just a place for prayer, but a vibrant centre for authentic Islamic education, a hub for social justice initiatives, a safe and welcoming space for women, children, and youth, and a base for selfless community service modelled on the spirit of Surah al-Insan — as mentioned earlier.

Clarify Our Foundation: From Haste to Wisdom (Hikmah)

Building a sacred space requires foresight. We must clarify the legal and religious status of our centres, heeding the wise counsel of our maraji’ regarding the sigheh of the mosque. The most pious act is not always the most obvious one. True piety involves planning for the long-term health and stability of our communities, ensuring that the foundations we lay today do not become obstacles for the generations of tomorrow.

The Community Centre — The Modern Sahn (Courtyard)

If the local mosque is the beating heart of the community, then the Islamic Community Centre is the modern sahn—the courtyard surrounding the heart, where the spiritual energy of prayer is translated into education, social action, and collective strength.

In an age where people gather as much for study and mobilisation as for ritual worship, the centre becomes a vital organ for the community’s health. Its functions are a direct continuation of the prophetic model: teaching authentic fiqh and Qur’an, but also fostering a curriculum of tabyin (clarification) that includes media literacy to resist propaganda, organizing social welfare projects, and creating a space to defend the oppressed.

This requires a governance structure rooted in Wilayah: transparent, scholar-led, and committed to safeguarding the dignity of every individual.

The theological lesson is profound: service becomes worship when it is tied to the principles of Wilayah, meaning it is guided by divine principles and aimed at strengthening the community of God’s friends.

The Centre as a Body: Nurturing Every Limb

The ultimate measure of a community centre’s success is how well it embodies the famous prophetic metaphor of the Ummah as a single body.

The Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him and his family) said:

مَثَلُ الْمُؤْمِنِينَ فِي تَوَادِّهِمْ وَتَرَاحُمِهِمْ وَتَعَاطُفِهِمْ مَثَلُ الْجَسَدِ إِذَا اشْتَكَى مِنْهُ عُضْوٌ تَدَاعَى لَهُ سَائِرُ الْجَسَدِ بِالسَّهَرِ وَالْحُمَّى

“The believers in their mutual kindness, compassion, and sympathy are just like one body. When one of the limbs suffers, the whole body responds to it with wakefulness and fever.”

— This narration is found in both Sunni and Shia sources, confirming its universal importance. See: Sahih Muslim, Hadith #2586 and its principle echoed in Al-Kulayni, Al-Kafi, Volume 2, Page 166

A true Islamic centre must be this living body, attentively caring for every one of its limbs.

This begins with the children, who are the future of the community. A centre that is not filled with the sounds of children’s joy is a centre that is dying.

The contemporary scholar Shaykh Alireza Panahian often reminds us:

مسجدی که برای بازی کودکان جا ندارد، در واقع برای آیندهی خود جا ندارد. باید جذابترین نقطه شهر برای فرزندان ما، مسجد و مرکز اسلامی باشد.

“A mosque that has no room for children to play, in reality, has no room for its own future. The most attractive place in the city for our children must be the mosque and the Islamic centre.”

— Shaykh Alireza Panahian, from his book Shahri dar Aseman (A City in the Sky), which is a compilation of his lectures on the spiritual dimensions of the mosque

This prophetic model was stunningly embodied in our own time by the master of the martyrs of our era, Hajj Qassem Soleimani.

In a famous and widely-circulated video, he is seen engrossed in his prayer when a small child approaches and playfully interacts with him. Without breaking his connection with God, he shows no sign of annoyance, gently accommodating the child with his hand.

The moment his prayer concludes, he immediately embraces the child with a loving hug.

In this beautiful act, Hajj Qassem was a perfect mirror of the Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him and his family) himself, who would famously lengthen his prostration (sujud) so as not to disturb his young grandson, Imam Husayn, who had climbed upon his back.

This is the true character of the believer and the lover of God: the most formidable in the face of tyranny are the most tender and merciful in the presence of the innocent.

This care extends to our elders, who are the roots and the memory of the community.

A centre must be a place where they are not forgotten, but are actively honoured, their wisdom sought, and their needs met.

They are the living connection to our heritage, and to neglect them is to sever the body from its own foundation.

Imam Khomeini saw their presence not as a burden, but as a source of divine blessing:

وجود سالمندان در هر خانواده و جامعهای، برکت است. احترام به آنان، احترام به تجربهها و ارزشهاست.

“The presence of the elderly in any family or society is a blessing (barakah). Respect for them is respect for experience and for values.”

— Imam Khomeini, Sahifeh-ye Imam, Volume 17, Page 22, from a speech delivered on September 28, 1982 (6 Mehr 1361)

Finally, a healthy body has an immune response; it rallies to aid any part that is in pain. This spirit of mutual support (takaful) is the highest form of worship.

The vanished leader, Imam Musa al-Sadr, founded his entire movement in Lebanon on this principle:

إن خدمة الإنسان هي أسمى أشكال العبادة لله. لا يمكن أن تدعي الإيمان وأنت لا تبالي بفقر جارك أو ألمه.

“Serving human beings is the highest form of worshipping God. You cannot claim to have faith while you are indifferent to your neighbor’s poverty or pain.”

— Imam Musa al-Sadr, a foundational principle of the Amal Movement and the Council for the South, Lebanon, circa 1970s

This is the ideal of an Islamic society.

The martyred intellectual and architect of the Islamic Republic, Shaheed Ayatullah Beheshti, described it as a community where no one is left behind:

در جامعه اسلامی، هیچکس گرسنه سر بر بالین نمیگذارد و هیچکس از تنهایی رنج نمیبرد و زیر بار تنهایی له نمیشود.

“In an Islamic society, no one lays their head on their pillow hungry, and no one suffers from loneliness or is crushed under the weight of loneliness.”

— Shaheed Ayatullah Muhammad Husayni Beheshti, from a speech on the principles of the Islamic constitution, delivered at the Assembly of Experts, September 5, 1979 (14 Shahrivar 1358)

This model is precisely what we see in the most resilient communities of our time.

The social support networks of the resistance in Lebanon are not separate from the resistance; they are the resistance.

Sayyed Hassan Nasrallah affirmed this in a speech marking the 25th anniversary of the Jihad al-Bina (Reconstruction Jihad) institution:

إن المقاومة ليست مجرد بندقية ومقاتل. المقاومة هي مجتمع متكامل... مؤسساتنا الاجتماعية والتربوية والصحية هي جزء أساسي من بنية هذه المقاومة وصمودها.

“The resistance is not just a rifle and a fighter. The resistance is an integrated society... Our social, educational, and health institutions are a fundamental part of the structure of this resistance and its steadfastness.”

— Sayyed Hassan Nasrallah, from a televised speech on Al-Manar, Beirut, Lebanon, August 26, 2013

In Yemen, Iraq and indeed Palestine, the resistance movements grew out of this same bedrock of social institutions. This is the practical lesson: true brotherhood (ukhuwwah) is built through service, and it is this bond that transforms a mere collection of individuals into a powerful, Godly collective, capable of enduring any hardship.

The Virtual Sahn (Courtyard): A Refuge and a Strategy

We must be honest, however. For many, the ideal physical centre remains out of reach. In the diaspora, our communities are often plagued by painful realities: nepotism, racism, factionalism, and a cliquishness that leaves new Muslims—be they reverts or recent migrants—feeling isolated and unwelcome.

In these situations, the virtual community—meeting on Zoom, or other platforms—has become an essential lifeline.

These online gatherings are not a lesser alternative; they are a crucial refuge where souls can find the authentic knowledge and sincere companionship they are denied locally.

They are a testament to the fact that the community of believers is, above all, a spiritual and ideological bond that transcends bricks and mortar.

The leaders of the resistance, who have operated for decades under conditions of war and siege, have long understood this principle.

Sayyed Hassan Nasrallah articulated this in the massive “Victory Rally” after the 2006 war, defining the true nature of the community:

إن مجتمع المقاومة ليس مجرد بيئة جغرافية، بل هو حالة وعي وإرادة وإيمان. هو مجتمع يتنفس ثقافة التضحية والكرامة، سواء اجتمع أفراده في حسينية أم في ملجأ تحت القصف. الرابط هو القلب والعقيدة.

“The society of resistance is not merely a geographical environment; it is a state of consciousness, will, and faith. It is a society that breathes the culture of sacrifice and dignity, whether its members are gathered in a Husseiniyya or in a shelter under bombardment. The bond is the heart and the creed.”

— Sayyed Hassan Nasrallah, from his Victory Rally speech, Beirut, Lebanon, September 22, 2006

However, these virtual communities have a sacred duty.

While nothing can replace face-to-face human interaction, their role is not to create a permanent alternative to the local centre, but to act as a base for reform.

They should encourage real-world gatherings where possible and, more importantly, become think tanks for healing our physical communities, devising strategies to lovingly and wisely challenge local problems so that our centres can one day become the welcoming sanctuaries they are meant to be.

The True Centre: The Sanctity of the Believer’s Heart

Ultimately, this brings us to the most profound truth: the ultimate centre of any community is not a building, but the sanctified hearts of its members.

If our centres, whether physical or virtual, become battlegrounds of ego that break the hearts of believers, they have failed.

The Ahl al-Bayt have taught us that the sanctity of a believer’s heart is paramount, rooted in the famous Divine Tradition:

لَا يَسَعُنِي أَرْضِي وَلَا سَمَائِي وَلَكِنْ يَسَعُنِي قَلْبُ عَبْدِيَ الْمُؤْمِنِ

“Neither My earth nor My heaven can contain Me, but the heart of My believing servant does contain Me.”

— Al-Fayd al-Kashani, ‘Ilm al-Yaqin, Volume 1, Page 93

Because the believer’s heart is a sanctuary for God Himself, to wound it is one of the gravest sins.

The great scholars of akhlaq (ethics) and irfan (gnosis) have issued the sternest warnings on this matter.

The philosopher and guide, Ayatullah Muhammad-Taqi Misbah-Yazdi, taught:

شکستن دل مؤمن از گناهان کبیرهای است که کمتر به آن توجه میشود. گاهی یک کلمه، یک نگاه تحقیرآمیز، یا یک بیتوجهی، حرمت خانهی خدا را در قلب یک انسان میشکند.

“Breaking a believer’s heart is among the major sins to which little attention is paid. Sometimes a single word, a contemptuous look, or an act of neglect shatters the sanctity of the House of God within a person’s heart.”

— Ayatullah Muhammad-Taqi Misbah-Yazdi, Akhlaq dar Qur’an (Ethics in the Qur’an), Volume 2, Page 245

The popular contemporary teacher, Shaykh Alireza Panahian, connects this directly to the health of our communities:

ریشه بسیاری از مشکلات در جوامع ما، عدم درک حرمت مؤمن است. جامعهای که در آن دلها به راحتی میشکند، جامعهای بیمار است و نمیتواند زمینهساز ظهور باشد.

“The root of many problems in our communities is the failure to understand the sanctity of a believer. A community in which hearts are easily broken is a sick community, and it cannot be the foundation for the Reappearance.”

— Shaykh Alireza Panahian, from his lecture series on preparing a Mahdavi Society, delivered during Muharram, circa 2015

Calls to Clarify: The Adab (etiquette) of the Modern Sahn (courtyard)

Clarify Our Foundation: Prioritise Hearts Over Bricks.

The true measure of a community centre’s success is not the size of its building or the number of its programs, but how it safeguards the hearts of its members.

We must clarify that any action—be it from leadership or laity—that fosters racism, cliquism, or arrogance, and makes a single believer feel unwelcome, is an act of spiritual destruction.

The first duty of a community is to have zero tolerance for anything that breaks the heart of a believer.

Clarify Our Mission: Balance the Spiritual and the Social

A centre that is all social but not spiritual becomes hollow; a centre that is all ritual but not social becomes irrelevant.

We must clarify that a true “modern sahn” must be both.

It must be a deep well for spiritual nourishment through authentic, scholar-led knowledge, prayer, and dua, and it must be an active hub for social justice, welfare projects, and serving the needs of the wider society, not just its own members.

Clarify Our Strategy: Use the Virtual to Heal the Physical

Virtual communities are a blessing, but they must clarify their ultimate purpose.

They are not meant to be permanent, isolated islands.

They should be seen as strategic training grounds and support networks that empower their members to become agents of positive change.

The goal should be to use the knowledge and solidarity gained online to lovingly and wisely diagnose and heal the problems in our local, physical centres, bringing the health of the virtual space into the real world.

The Earth as a Masjid: Sanctifying the Home and the Public Square

From the semi-public courtyard of the community centre, our journey now arrives at its final destinations: the most intimate sanctuary of the home, and the most open sanctuary of the world outside.

If the great shrines are the spiritual peaks, our homes and streets are the valleys where we must make their light shine.

This final point is about understanding that sanctity is not confined to special buildings, but can be cultivated wherever a believer stands, guided by the profound declaration of the Prophet.

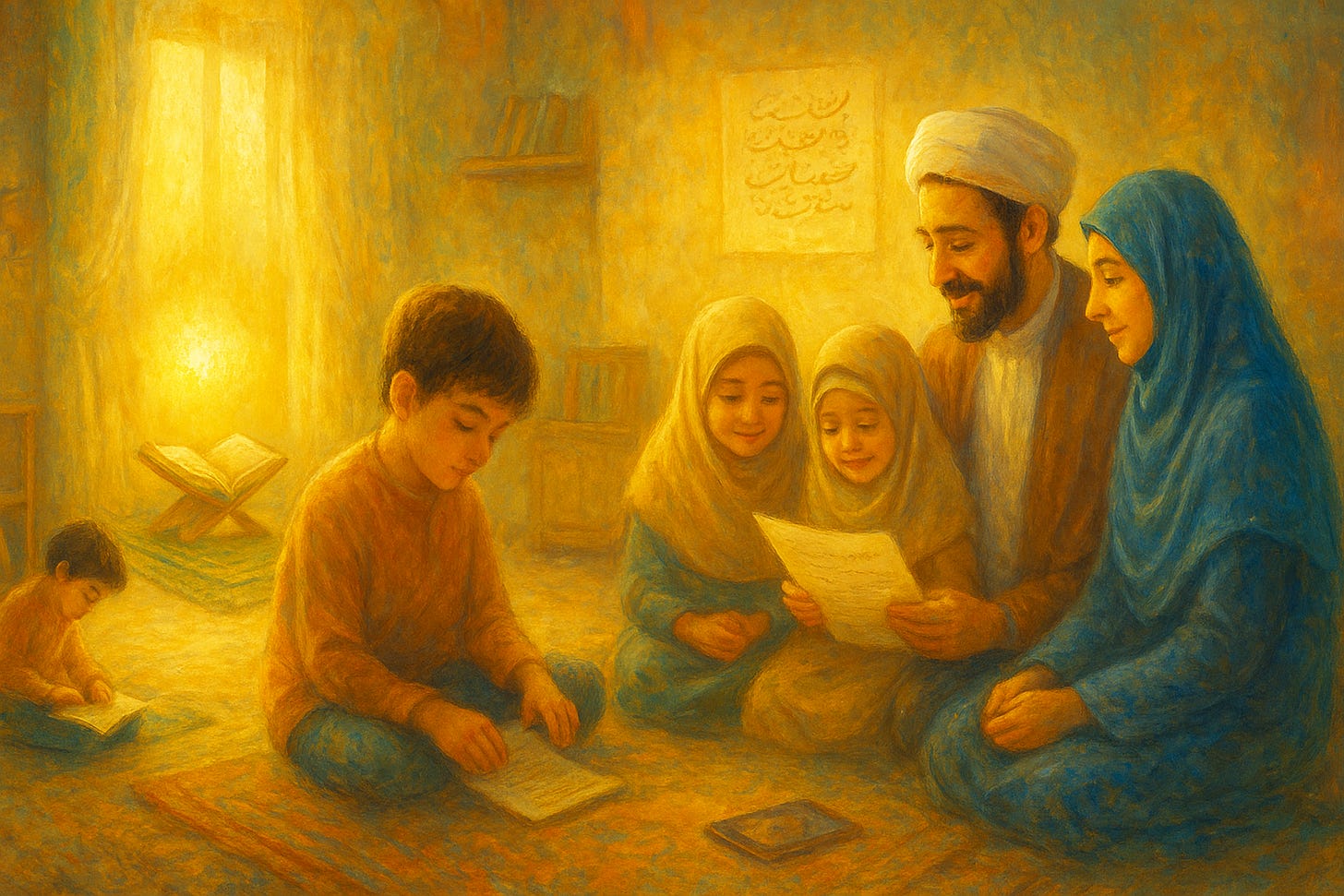

The Home — The First Sanctuary and Micro-Wilayah

The home is the first school (madrasa) and the first fortress where the believer’s soul is nurtured.

Its primary purpose, as established by Prophet Ibrahim (peace be upon him) at the very foundation of his family, is to be a sanctuary for the establishment of prayer:

رَّبَّنَآ إِنِّىٓ أَسْكَنتُ مِن ذُرِّيَّتِى بِوَادٍ غَيْرِ ذِى زَرْعٍ عِندَ بَيْتِكَ ٱلْمُحَرَّمِ رَبَّنَا لِيُقِيمُوا۟ ٱلصَّلَوٰةَ

“Our Lord, I have settled some of my descendants in an uncultivated valley near Your sacred House, our Lord, that they may establish prayer.”

— Qur’an, Surah Ibrahim (the Chapter of Abraham) #14, Verse 37

The character of one’s conduct within this sanctuary is the ultimate measure of their faith.

The Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him and his family) declared:

خَيْرُكُمْ خَيْرُكُمْ لِأَهْلِهِ وَأَنَا خَيْرُكُمْ لِأَهْلِي

“The best of you are the best to your families, and I am the best of you to my family.”

— Shaykh al-Saduq, Man La Yahduruhu al-Faqih, Volume 3, Page 443, Hadeeth 4538

The great scholar on family ethics, Ayatullah Ibrahim Amini, emphasized that the home is the primary institution of education:

خانه اولین و مهمترین مدرسهای است که شخصیت کودک در آن شکل میگیرد. سعادت و شقاوت هر انسانی در درجه اول به تربیت خانوادگی او بستگی دارد.

“The home is the first and most important school in which a child’s personality is formed. The happiness and misery of every human being depends, in the first degree, on their family upbringing.”

— Ayatullah Ibrahim Amini, The Ideal Family, Introduction

The Micro-Wilayah: A Covenant of Love and Responsibility

Wilayah (guardianship) is not about domination, but about a sacred trust and responsibility, rooted in the Qur’anic command:

يَـٰٓأَيُّهَا ٱلَّذِينَ ءَامَنُوا۟ قُوٓا۟ أَنفُسَكُمْ وَأَهْلِيكُمْ نَارًا

“O you who have believed, protect yourselves and your families from a Fire...”

— Qur’an, Surah al-Tahrim (the Chapter of the Prohibition) #66, Verse 6

This “protection” is the essence of wilayah.

The roles within the family are a covenant of complementary responsibilities.

This has been clarified by our great scholars, such as Ayatullah Jawadi-Amoli, who explains that the Qur’anic concept of qiwamah (guardianship) for men is a burden of responsibility, not a license for privilege:

قوّام بودن مرد به معنای آن نیست که او افضل است، بلکه به معنای آن است که مسئولیت اجرایی و تأمین نیازهای خانواده بر عهده اوست. این یک وظیفه است، نه یک فضیلت.

“A man being a ‘guardian’ (qawwam) does not mean he is superior; rather, it means that the executive responsibility and provision for the family’s needs are upon his shoulders. This is a duty, not a virtue.”

— Ayatullah Abdollah Javadi-Amoli, from his Tafsir on Surah an-Nisa, verse 34, in his book Zan dar Ayineh-ye Jalal wa Jamal (Woman in the Mirror of Majesty and Beauty)

This covenantal understanding shapes the adab (etiquette) of the home: conflicts are resolved with mercy and privacy, hospitality is extended as a form of da’wah, and shared dhikr becomes the foundation of family unity.

The Outdoors — Reclaiming the Public Square for God

This act of sanctification is not confined to our four walls. It extends to the entire world, based on the expansive vision of the Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him and his family):

أُعْطِيتُ خَمْساً... وَجُعِلَتْ لِيَ الْأَرْضُ مَسْجِداً وَطَهُوراً

“I have been given five things... and the earth has been made for me a place of prostration (masjid) and a means of purification (tahur).”

— Shaykh al-Saduq, Man La Yahduruhu al-Faqih, Volume 1, Kitab al-Salat (The Book of Prayer), Page 226, Hadeeth 678

This hadith transforms every park, garden, and public space into a potential prayer niche.

Nature itself is a book of divine signs, a primary text for reflection (tafakkur):

أَفَلَا يَنظُرُونَ إِلَى ٱلْإِبِلِ كَيْفَ خُلِقَتْ وَإِلَى ٱلسَّمَآءِ كَيْفَ رُفِعَتْ

“Then do they not look at the camels—how they are created? And at the sky—how it is raised?”

— Qur’an, Surah al-Ghashiyah (the Chapter of the Overwhelming) #88, Verses 17-18

The theological lesson is profound: sacredness is not confined.

This is a revolutionary act against a secular culture that seeks to privatise faith.

Imam Khomeini rejected this notion, stating:

اسلام دین سیاست است، دینی که در تمام شئون زندگی فردی و اجتماعی دخالت دارد. اسلام را محبوس در مساجد نکنید.

“Islam is the religion of politics; a religion that intervenes in all aspects of individual and social life. Do not imprison Islam within the mosques.”

— Imam Ruhollah Khomeini, Sahifeh-ye Imam, Volume 6, Page 47, from a speech delivered on September 1, 1979

To reclaim public space for remembrance and service—a reflection walk, a food run—is to live this principle.

Calls to Clarify: Living as Map-Makers of Sacred Space

Clarify Your Foundation: From Shelter to Sanctuary

We must clarify that a the home is more than a place to eat and sleep.

This means consciously designing it for its sacred purpose.

Establish a dedicated corner for prayer and study.

Write a “family covenant” based on the Qur’anic principles of mutual mercy and responsibility.

Implement ethical tech rules to protect the home from the invasion of heedlessness.

Clarify Your Presence: From Consumer to Consecrator

When we step outside, we must clarify our role.

We are not just consumers; we are vicegerents (khalifa).

Transform a simple walk into a reflection (tafakkur) walk, consciously observing the signs of God in nature.

Turn a coffee shop meeting into a study circle.

Organise a monthly public service morning that reclaims public space for the values of wilayah.

Clarify Your Intention: The Power That Sanctifies All Space

Ultimately, what transforms any space from profane to sacred is the believer’s intention (niyyah).

A home or park can become more beloved to God than a misused mosque if His remembrance is alive there.

We must clarify in our hearts that every action can be an act of worship, as taught in the intimate whispered prayer (munajat) of Imam Sajjad (peace be upon him):

وَاجْعَلْ هَمَسَاتِ قُلُوبِنَا، وَحَرَكَاتِ أَعْضَائِنَا، وَلَمَحَاتِ أَعْيُنِنَا... مُوجِبَاتٍ لِثَوَابِكَ

“And make the whispers of our hearts, the movements of our limbs, the glances of our eyes... all lead to Your reward.”

— Imam Ali ibn al-Husayn, from the Munajat al-Muti’in lillah (The Whispered Prayer of the Obedient to God)

Conclusion

The Map-Makers of a Sacred World

Tonight, our journey through the sacred windows of place has finally come home. We have descended from the great peaks of global pilgrimage to the valleys of our daily lives, learning that sanctity is not a distant reality to be visited, but a living truth to be cultivated.

We began with our local mosque, clarifying that it is not a private club, but God’s own house—a beating heart for the community that must be a sanctuary of radical inclusion, authentic knowledge, and selfless service.

We then moved to the community centre, the modern sahn or courtyard, understanding it as a living body. We learned that its health depends on nurturing every limb—from the youngest child to the most senior elder—and that its ultimate purpose is to safeguard the sanctity of every believer’s heart.

Finally, we entered the most intimate sanctuary of the home, framing it as a micro-wilayah and a fortress of faith against the invasion of heedlessness. From there, we stepped out into the world, realising that the entire earth has been made a masjid, and that our intention (niyyah) has the power to transform any space—a park, a garden, a street corner—into a station for the remembrance of God.

The ultimate lesson is this: the purpose of the great shrines is not to confine holiness, but to teach us how to recognise and create it everywhere. We are all called to be map-makers of a sacred world.

A map that takes us towards the Beloved.

Epilogue: The Sacred Windows — The Role of Place

Our journey through the sacred windows of place is now complete — for now.

We began with a simple question: where does the earth meet heaven for a believer? Our path has taken us from the primordial foundations of our faith to the very living rooms and streets where we live out our days.

We first stood at the divine anchors of our sacred geography: the primordial sanctuary of Makkah, the prophetic community of Madinah, and the covenantal bridge of al-Quds. These are the great poles of revelation, from which all other sanctity flows.

From there, our journey took us through a profound syllabus. We travelled to the triangle of Iraq—The Crucible, The Criterion and the Citadel.

In Kufa, we learned the price of hesitation.

In Karbala, we witnessed the ultimate proof of sacrifice.

And in Najaf, we found the fortress of preservation.

Together, they forged our intellect and steeled our resolve.

Our path then turned to the sanctuaries of the heart—The Sanctuary, The Saint, and The Sacrifice.

In Mashhad, we were immersed in the ocean of divine mercy.

In Qom, we learned the power of loyalty and intercession.

And in the gardens of the martyrs, we corrected our fear of death and understood the meaning of courage.

Together, they shaped our spirit with compassion, fidelity, and fearlessness.

Next, our journey led us to the thresholds of concealment and continuity—to The Prison, The Portal and the Presence.

In the dungeons of Kadhimiyyah, we learned from the imprisoned light of Imam al-Kadhim that divine authority cannot be chained.

At the gateway of Samarra, we stood at the portal to the Unseen, learning that the Occultation demands active preparation.

And through the shrines of the Imamzadehs, we traced the dispersed presence of the Ahl al-Bayt across the globe, understanding that the chain of God’s proof is never broken.

Finally, having toured these great peaks, we brought all their lessons home.

In our own local mosques, community centres, and homes, we learned that the purpose of visiting the great sanctuaries is to learn how to sanctify our own valleys, and that every believer is called to be a map-maker of a sacred world.

The ultimate lesson of sacred geography is this: the most sacred place of all is the purified heart of a believer. And the greatest act of worship is to take that purified heart and use it to make our small corner of the world a sacred space—a place of justice, remembrance, and mercy, preparing the earth for the arrival of its true Inheritor.

Whispers Beneath the Throne

The Map-Maker’s Prayer

In Your Name,

O Lord of the Primordial House and the Prophetic City,

O Lord of the lands of trial and the sanctuaries of the heart,

O Lord of the hidden corners where we whisper Your Name.O God,

pour Your boundless blessings upon Muhammad, the Seal of Prophets;

upon Ali, the Gate of Knowledge;

upon Fatimah, the Lady of Light;

upon Hasan, the Mirror of Patience;

upon Husayn, the Artery of Justice;

and upon the Imams from their progeny,

the lanterns of Your guidance in the deepest night.O Lord,

we have journeyed with our hearts through the sacred windows of place. Grant us now the fruits of this journey.

Grant us the conviction of Karbala to stand for truth and deliver us from the hesitation of Kufa.

Fill our hearts with the mercy of Mashhad,

the loyalty of Qom,

and the courage of the martyrs.

Discipline our minds with the knowledge of Najaf.Sanctify our mosques—

make them fortresses of justice,

reflecting the covenant of Al-Quds.

Sanctify our centres—

make them living bodies of compassion,

reflecting the community of Madinah.Sanctify our homes—

make them gardens of remembrance and sanctuaries of Wilayah.

Sanctify our parks and our streets—

make them safe for the oppressed and luminous with Your Name.O Lord,

we ask You by the right of those who embodied these lessons and walked these sacred paths in our own time.

Unite us with Your righteous servants:

with the Commander of Hearts, Hajj Qassem Soleimani;

with the loving elder brother of the believers, Hajj Imad Mughniyeh;

and with our beloved master and martyr, Sayyed Hassan Nasrallah.

Grant us a portion of their sincerity, their insight (basirah),

and their unwavering loyalty to Your Wali,

so that we may continue their path.By the sanctity of their shed blood,

we ask You to heal the broken,

defend the displaced,

and uplift the oppressed—

in Gaza, in Palestine, in Syria, in Lebanon, in Yemen,

in every land afflicted by tyranny.

Do not let us be among those who pray in shrines but forget the streets. Make us Your servants in every place.And hasten the reappearance of Your Proof,

Our beloved Imam al-Mahdi (may our souls be his ransom),

so that we may pray with him in Makkah, Madinah and al-Quds,

in Kufa, Karbala and Najaf,

in Qom, Mashhad and the graveyards of the pure,

and in every neighbourhood and home,

until the earth is filled with justice,

and every place becomes a sacred space,

and every believer a true map-maker for Your sake.For the sake of Muhammad and the Family of Muhammad,

Our Beloved Master, heed our prayer.Amen, O Lord Sustainer of the Universe

Amen, O Most Merciful of the Merciful

And from Him alone is all ability and He has authority over all things.

Regarding the topic of the article, your analysis is profoundly insightful.