[2] The Joy of Fasting - The Purification of the Mirror - Cleansing the Heart

The Joy of Fasting: A Special Series for the Month of Ramadhan 1447 / 2026 Studying the Subject of Fasting and Attaining Closeness to God, Especially during the blessed Month of Ramadhan

In His Name, the Most High

Introduction and Recap

Last week, we talked about leaving.

We said that fasting, properly understood, is not an act of staying still — it is an act of movement.

A migration.

A departure from the house of the self, the structure of habits and reactions and demands that we have built around ourselves brick by brick until the walls became invisible.

We identified the lock on the door — the idol of the ego, the Pharaoh within — and we said that fasting is the first crack in that idol, the first defiance of that tyrant.

We named one piece of furniture in the house and committed to removing it.

And we heard the Prophet, peace be upon him and his family, tell us that we have not been abandoned on the road — we have been invited.

Invited to the banquet of God.

That is where we left off.

But here is the thing about migration.

You do not flee a burning house to stand in the street.

You leave one place because you are going to another.

And when you arrive — when you reach the door of wherever it is you were heading — there is a moment that every traveller knows.

You look down at yourself.

You see the dust on your clothes, the mud on your shoes, the grime of the road on your face and hands.

And you think:

I cannot walk in like this.

Not because the Host will turn you away — we said last week that this Host is the Most Generous, the Most Merciful, the One who prepared the banquet before you ever thought to set out.

But because something in you knows that the occasion demands more than showing up.

It demands showing up clean.

Think of the last time you were invited somewhere that mattered to you.

A wedding.

A meeting with someone you deeply respected.

A gathering where you wanted to be your best self.

What did you do before you went?

You showered.

You chose your clothes carefully.

You checked the mirror.

Not out of vanity — out of respect.

Out of the understanding that the occasion itself asks something of you.

The Month of Ramadhan is that occasion.

And the tradition tells us that the preparation required is not only physical.

It is not only about the body’s cleanliness, though that matters.

It is about the state of the heart.

Because you can arrive at the most magnificent banquet on earth in a spotless suit — and carry inside you a heart so coated in dust and rust and the residue of a year’s worth of heedlessness that you cannot taste a single thing on the table.

The food is there.

The light is there.

The Host is there.

But you cannot receive any of it.

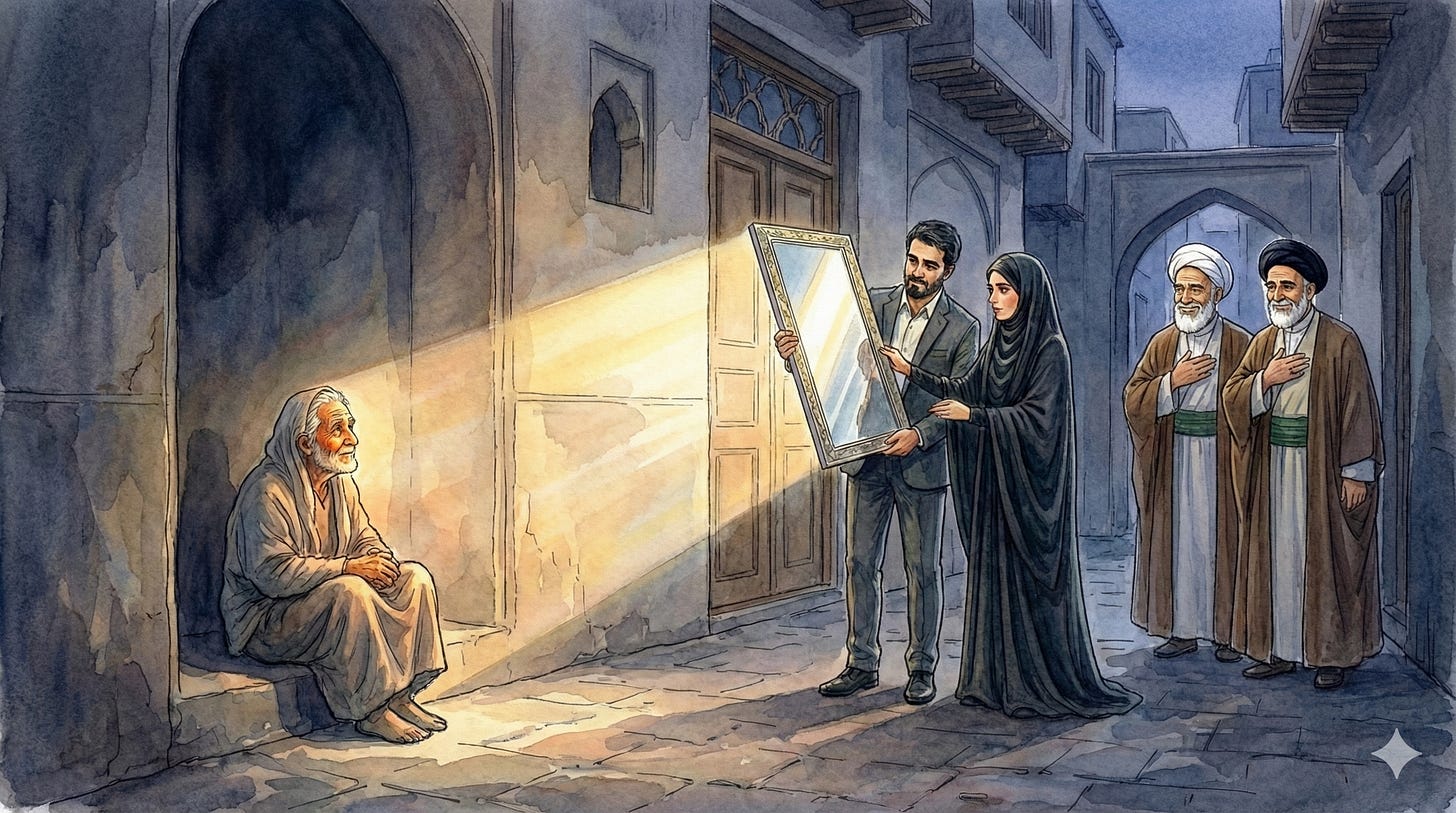

Because the mirror of the heart — the instrument through which we perceive the Divine — is covered.

Tonight, we talk about cleaning that mirror.

We said last week that the journey has four stages: surrender, faith, migration, struggle.

Tonight we are between stages — we have begun the migration, and now we must prepare ourselves for what lies ahead.

We are on the road, and the road is dusty, and there is a river up ahead, and the tradition is telling us: stop here.

Wash.

You will need to be clean for what comes next.

This is Session 2: The Purification of the Mirror.

How to cleanse the heart so that it can receive the Light.

Movement 1: The Core Concept — Sin as Grime, Worship as Washing

The River at Your Door

Before we open any book of mysticism, before we enter the world of spiritual stations and inner states, the Prophet Muhammad, peace be upon him and his family, gives us an image so simple and so vivid that it needs no commentary to land.

Imam Ali, the Commander of the Faithful, peace be upon him, narrates in the Nahj al-Balagha that the Prophet said:

«إنَّما مَثَلُ الصَّلاةِ فيكُم كَمَثَلِ السَّرِيِّ ـ و هو النَّهرُ ـ على بابِ أحَدِكُم يَغتَسِلُ مِنهُ في اليَومِ و اللَّيلَةِ خَمسَ مَرّاتٍ ، فما عَسى أن يَبقى مِنَ الدَّرَنِ علَيهِ ؟»

“Verily, the likeness of prayer among you is like that of a running stream — as-sari — at the door of one of you, in which he washes himself five times during the day and night. What, then, could possibly remain of filth upon him?”

— Narrated by Imam Ali from the Prophet Muhammad; cited by Ayatullah Jawadi-Amoli, Hikmat-e Ibadat (The Wisdom of Worship), Page 93, Nashr-e Esra, Qum; also referenced in his Asrar al-Salat (Secrets of Prayer), where Imam Ali’s narration is attributed to Nahj al-Balagha

A river.

Not a bucket of water you must haul from a distant well.

Not a reservoir you must travel to reach.

A river — as-sari, a flowing stream — at your door.

Right there.

Steps from where you sleep.

Waiting for you every morning and every evening.

And the Prophet is asking — with the gentlest of rhetorical questions — what possible dirt could remain on a person who steps into this river five times a day?

The answer, of course, is: none.

If you actually bathe in it.

And this is where Ayatullah Jawadi-Amoli pauses on the hadith and makes an observation that turns it from a beautiful metaphor into a diagnosis.

He writes — and I want you to hear the honesty in this:

«نماز مثل چشمه زاللى است كه انسان نمازگزار در اين وقتهاى پنج گانه در آن شستوشو مىكند . نماز كوثرى است كه انسان را تطهير مىكند . قهرا اگر ما از نماز اين طهارت را در خود احساس نكرديم بايد بپذيريم كه آن نماز واقعى را نخواندهايم . ممكن است نمازمان صحيح باشد، لكن مقبول نيست، زيرا آن نمازى مقبول است كه روح انسان را تطهير كند و با انسان سخن گويد و او را مژده دهد.»

“Prayer is like a pure spring in which the one who prays washes at these five times. Prayer is a Kawthar — an abundant river — that purifies the human being. Naturally, if we do not feel this purification from prayer within ourselves, we must accept that we have not truly prayed. Our prayer may be valid (sahih), but it is not accepted (maqbul) — because the prayer that is accepted is one that purifies the soul, speaks to the human being, and gives them glad tidings.”

— Ayatullah Jawadi-Amoli, Hikmat-e Ibadat (The Wisdom of Worship), Page 93, Nashr-e Esra, Qum, 5th Edition; also cited in his Asrar al-Salat (Secrets of Prayer), where the hadith is attributed to Imam Ali narrating from the Prophet via Nahj al-Balagha

The Illusion of Cleanliness

Read that again.

The river is there.

It has always been there.

It flows at the door of every single one of us, five times a day, without fail.

And yet most of us — if we are honest — do not feel clean.

We pray, and we do not feel purified.

We fast, and we do not feel lighter.

We worship, and the grime remains.

Not because the river has dried up.

Not because the water has lost its power.

But because — and this is the point that will anchor everything we discuss tonight — we are not truly stepping into it.

We are standing at the edge, going through the motions of bathing, and walking away still covered in dust.

The prayer is valid.

The fast is valid.

The form is correct.

But the purification has not reached the heart.

Now — notice something about the image the Prophet chose.

He did not say

“the likeness of prayer is like a bath you take once a year.”

He said:

five times a day.

Every day.

Why?

Because we get dirty every day.

Not because we are terrible people.

Not because we are sinners beyond redemption.

But because engagement with the material world — its anxieties, its distractions, its demands, its constant pull on our attention and our desires — leaves residue on the soul.

Every argument you had today left a residue.

Every moment of heedlessness — the scroll through the phone, the prayer you rushed through, the person you ignored — deposited a thin layer of dust on the mirror of the heart.

Every flash of anger, every pang of envy, every transaction where you were less than honest — not necessarily with others, but with yourself — added to the film.

This is not guilt-tripping.

This is spiritual hygiene.

No one is ashamed of needing a shower after a day’s work.

The body gets dirty because it exists in the physical world.

The soul gets dirty because it exists in the material world.

Both need washing.

Both need it regularly.

And the five daily prayers are that regular wash.

The Deep Clean

But here is the Ramadhan move — and this is the turn that matters for us tonight.

If the five daily prayers are a daily shower, what is the Month of Ramadhan?

The Month of Ramadhan is the deep clean.

It is the annual immersion.

Thirty days submerged in the river — not five quick splashes, but a sustained soaking designed to reach the grime that daily prayer alone cannot dislodge.

The dirt that has calcified.

The habits that have hardened into crust.

The sins of the tongue and the eyes and the heart that have been accumulating for months, for years, layer upon layer, until they no longer feel like dirt at all — they feel like skin.

That is what this month is for.

Not endurance.

Not performance.

Not the grim satisfaction of having survived another day without food.

Washing.

Deep, sustained, thorough washing — of things we have stopped noticing are dirty.

The Mirror and the Rust

And now I want to layer in a second image — one that goes deeper than the river, because it addresses not just the dirt on the surface but the condition of the instrument itself.

The Prophet Muhammad, peace be upon him and his family, said:

«لِكُلِّ شَيْءٍ صِقَالَةٌ، وَصِقَالَةُ الْقُلُوبِ ذِكْرُ اللَّهِ»

“For everything there is a polish [to remove rust], and the polish of the hearts is the remembrance of God.”

— Al-Bayhaqi, Shu’ab al-Iman, Hadith No. 522, narrated by Abdullah ibn Umar; also narrated from Imam Ali in Allamah Majlisi, Bihar al-Anwar, Volume 90, Page 151; Ghurar al-Hikam

And in a related narration from Imam Ali, peace be upon him, the image is sharpened further:

The hearts rust just as iron rusts — and their polish is the remembrance of God.

Sit with that word: siqalah — polish.

Not cleaning.

Not wiping.

Polishing.

Cleaning removes dirt from a surface.

Polishing does something more — it restores the surface’s capacity to reflect.

A dirty mirror and a rusted mirror are not the same thing.

A dirty mirror has something on top of it — wipe the dirt away and the reflection returns. But a rusted mirror has been corroded from within.

The reflective surface itself has been damaged.

You cannot just wipe rust off.

You have to scrub.

You have to apply friction, abrasion, sustained pressure — until the metal underneath is exposed again and can do what it was made to do.

Reflect.

And this is the image the tradition gives us for the heart.

The heart is a mirror.

Its purpose — its entire reason for existing — is to reflect the Light of God.

That is what it was designed for.

That is what it does when it is healthy, when it is clean, when it is functioning as it was created to function.

But sin, heedlessness, and worldly attachment do not merely leave dirt on the surface.

They rust it.

They corrode its reflective capacity from within.

The Quran uses a specific word for this:

كَلَّا ۖ بَلْ ۜ رَانَ عَلَىٰ قُلُوبِهِم مَّا كَانُوا۟ يَكْسِبُونَ

“No indeed! Rather, what they have been earning has rusted upon their hearts.”

— Quran, Surah al-Mutaffifin (the Chapter of Those Who Give Short Measure) #83, Verse 14

Rana — it has rusted over.

It has encrusted.

It has formed a layer so thick that the heart can no longer receive what is being sent to it.

And when the mirror is rusted, it does not matter how bright the sun is.

The mirror reflects nothing.

The problem is not the absence of Light.

The Light is always there — God is always radiating, always present, always offering.

The problem is the state of the mirror.

This is why some people can stand in prayer and feel nothing.

This is why some people can fast for thirty days and taste no sweetness.

This is why the Quran can be recited in a room and some hearts are moved to tears while others check their phones.

The Light did not change.

The mirror did.

Fasting as Friction

And this brings us to fasting — specifically, to the mechanism by which fasting addresses not just the dirt but the rust.

Fasting is friction.

That is its function at the deepest level.

Hunger and thirst are the abrasive that scrubs the corroded surface of the heart.

They do not do it gently — we said last week that the ego does not let you leave quietly, and here, the ego does not let you clean it without resistance.

The discomfort you feel in the fast is not punishment.

It is the friction of rust being scraped away.

It is the sound of the mirror being restored.

But — and this is the critical turn that bridges us into the next movement — the scrubbing only works if it reaches the whole mirror.

Not just one corner.

A person who stops eating and drinking has polished one small section of the mirror — the section that deals with appetite, with bodily desire, with the stomach’s demand to be filled.

But what about the rest?

What about the section rusted over by the tongue — by gossip, by cruelty, by lies?

What about the section corroded by the eyes — by what they consume, what they stare at, what they refuse to see?

What about the section eaten away by the ears — by the idle talk they absorb, the backbiting they entertain, the cries of the oppressed they choose not to hear?

If you polish one corner of a mirror and leave the rest caked in rust, the mirror still reflects nothing.

And this is the question that will take us into the heart of tonight’s session.

We often treat the Month of Ramadhan as spiritual maintenance — a tune-up, a service, a way of keeping things ticking over until next year.

But the tradition describes something far more radical: a deep restoration.

A scrubbing so thorough that it reaches parts of the heart we have forgotten are dirty.

The question is not:

am I fasting?

The question is:

what is my fast actually cleaning?

Movement 2: The Inward Lesson — The Three Ranks of Fasting

The Entry Ticket and the Banquet Hall

So far, we have established two things.

First: the soul accumulates grime — not because we are wicked, but because we are alive and engaged with the world.

This is normal.

This is expected.

The river flows at our door precisely because we need it every day.

Second: fasting is not merely abstention.

It is friction — the sustained abrasion that scrubs not just the surface dirt but the rust that has corroded the mirror of the heart from within.

But now we must ask the question that most of us avoid.

What, exactly, is this fast supposed to be cleaning?

Because the tradition does not leave this vague.

It does not say: fast, and good things will happen.

It gives us a very specific map of what the fast must reach if it is to do its work.

And that map has levels.

The great scholar and spiritual wayfarer, Mirza Jawad Maliki Tabrizi — may God rest his pure soul — lays this out with a clarity that leaves no room for comfortable ambiguity.

In his masterwork on the spiritual disciplines of the year, Al-Muraqabat (The Observances), he writes in the chapter on the observances of the blessed Month of Ramadhan:

«مراتب الصوم ثلاثة: صوم العوام، وهو بترك الطعام والشراب والنساء على ما قرره الفقهاء من واجباته ومحرماته. وصوم الخواص، وهو ترك ذلك مع حفظ الجوارح من مخالفات الله على الجملة. وصوم خواص الخواص، وهو ترك كل ما هو شاغل عن الله من حلال أو حرام.»

“The ranks of fasting are three: the fasting of the common people, which is to leave food, drink, and sexual relations as the jurists have established in its obligations and prohibitions. The fasting of the elite, which is to leave all of that while also guarding the limbs from disobedience to God in general. And the fasting of the elite of the elite, which is to leave everything that distracts from God — whether lawful or unlawful.”

— Mirza Jawad Maliki Tabrizi, Al-Muraqabat fi A’mal al-Sanah (Observances in the Acts of the Year), Chapter: Muraqabat (Observances) of the Blessed Month of Ramadhan

Read those three tiers again.

Slowly.

The first rank — sawm al-’awam, the fasting of the common people — is what most of us think fasting is.

No food.

No drink.

No physical intimacy.

From dawn to sunset.

You know the rules.

You have known them since childhood.

And let us be absolutely clear: this rank is necessary.

It is the door.

Without it, there is no fast at all.

The jurists have detailed its conditions, and they must be honoured.

But Mirza Maliki Tabrizi is telling us that this — all of this — is the entry ticket.

It gets you through the door.

It does not seat you at the table.

The second rank — sawm al-khawas, the fasting of the elite — is where the fast begins to touch the mirror.

Here, the fast extends beyond the stomach to every limb.

The tongue fasts from gossip, cruelty, and lies.

The eyes fast from what they should not consume.

The ears fast from what they should not entertain.

The hands fast from what they should not take or strike.

The feet fast from where they should not walk.

This is the fast that reaches the rust.

And the third rank — sawm khawas al-khawas, the fasting of the elite of the elite — is the fast of those who have emptied themselves so thoroughly that nothing remains in the heart except God.

Not just the forbidden is abandoned, but anything that distracts — even what is technically permissible — if it pulls the heart’s attention away from the Divine.

Now — before your mind rushes to dismiss this as the province of saints, as something beautiful but unreachable, pause.

Mirza Tabrizi does not present these ranks to make you feel inadequate.

He presents them so you know where you are, and so you know where the road goes.

A traveller is not humiliated by learning that the journey is long.

He is humiliated only if he mistakes the first mile for the destination.

And most of us — if we are honest — have been mistaking the first mile for the destination our entire lives.

We have been performing the fast of the stomach and calling it Ramadhan.

Valid but Not Accepted

This is where Imam Khomeini, may God rest his pure soul, enters and sharpens the blade.

In Adab as-Salat (The Disciplines of Prayer), in his discussion of the purifications required for genuine worship, he draws a distinction so precise and so devastating that it deserves to be engraved on the wall of every mosque and every home where a Muslim prays and fasts.

He distinguishes between al-ijza’ — sufficiency, validity — and al-qabul — acceptance.

«فاعلم أنّ القبول والإجزاء بينهما فرق. القبول من العبادة ما يترتّب عليه الثواب في الآخرة وتقرّب إلى الله زلفى. والإجزاء ما يسقط التكليف عن العبد وإن لم يُثَب عليه.»

“Know that there is a difference between acceptance and sufficiency. Acceptance in worship is that upon which reward is granted in the hereafter, and through which one draws near to God. Sufficiency is merely that which removes the obligation from the servant — even if no reward follows from it.”

— Imam Khomeini, Adab as-Salat (The Disciplines of Prayer), Chapter on the Purifications and Ablution

Let that land.

Your fast can be valid — technically correct, jurisprudentially sound, not a single rule broken — and still not be accepted.

Valid means the obligation is discharged.

You will not be punished for having missed it.

The box is ticked.

The form is filed.

But accepted — maqbul — means something happened.

Something moved.

The fast actually reached the heart, scrubbed the mirror, brought you one step closer to the One you were fasting for.

This is exactly what Ayatullah Jawadi-Amoli was pointing to when he said about prayer — and the same applies, word for word, to fasting:

«ممكن است نمازمان صحيح باشد، لكن مقبول نيست، زيرا آن نمازى مقبول است كه روح انسان را تطهير كند.»

“Our prayer may be valid, but it is not accepted — because the prayer that is accepted is one that purifies the soul.”

— Ayatullah Jawadi-Amoli, Hikmat-e Ibadat (The Wisdom of Worship), Page 93

Substitute “prayer” for “fasting” and read it again:

Our fast may be valid, but it is not accepted — because the fast that is accepted is one that purifies the soul.

The question, then, is not whether you are fasting.

You are.

The question is whether your fast is doing anything.

Is it valid?

Almost certainly.

Is it accepted?

That depends on what it is cleaning.

The Woman Who Was Told to Eat

And now — the moment that should stop us in our tracks.

Mirza Maliki Tabrizi narrates, in the same chapter of Al-Muraqabat, from Abu Abdillah — Imam al-Sadiq, peace be upon him:

«إنّ أبا فلان قال: سمع رسول الله صلّى الله عليه وآله امرأةً تسابّ جاريةً لها وهي صائمة، فدعا رسول الله صلّى الله عليه وآله بطعام فقال لها: كُلِي. فقالت: أنا صائمة يا رسول الله. فقال: كيف تكونين صائمةً وقد سَبَبْتِ جاريتك؟ إنّ الصوم ليس من الطعام والشراب، وإنّما جعل الله ذلك حجاباً عن سواهما من الفواحش من الفعل والقول يُفطر الصائم. ما أقلّ الصوّام وأكثر الجواع!»

“A man narrated: The Messenger of God, peace be upon him and his family, heard a woman cursing her servant-girl while she was fasting. So the Prophet called for food and said to her: ‘Eat.’ She said: ‘I am fasting, O Messenger of God.’ He said: ‘How can you be fasting when you have just cursed your servant? Fasting is not merely from food and drink. Rather, God made that a barrier against what is beyond them — the obscenities of action and speech that break the fast of the one who fasts. How few are those who truly fast, and how many are those who are merely hungry!’”

— Mirza Jawad Maliki Tabrizi, Al-Muraqabat fi A’mal al-Sanah, Chapter: Muraqabat of the Blessed Month of Ramadhan; hadith narrated via Imam al-Sadiq, referenced in Bihar al-Anwar

Read that last line again.

How few are those who truly fast, and how many are those who are merely hungry.

The Prophet did not say:

your fast is reduced.

He did not say:

you have lost some reward.

He did not say:

try to be nicer next time.

He said:

eat.

Your fast is already broken.

Not by food — by your tongue.

You polished one corner of the mirror — the corner that deals with appetite — and left the rest caked in rust.

And a mirror with one clean corner reflects nothing.

This is not a soft teaching.

This is not a suggestion.

This is the Prophet of God telling a fasting woman that her empty stomach means nothing — nothing — because her tongue is full.

And before we distance ourselves from this woman, before we tell ourselves that we would never curse a servant — ask yourself what your tongue did today.

What it did yesterday.

What it does every Ramadhan while your stomach sits empty and righteous.

The backbiting at the iftar table.

The sharp word to your spouse when the hunger made you irritable.

The gossip exchanged over suhoor, dressed up as concern.

The social media post that mocked, that belittled, that tore someone down — typed with fingers that had not touched food or water since dawn.

The Prophet is not speaking to that woman alone.

He is speaking to every one of us who has ever confused an empty stomach with a clean heart.

The Audit of the Limbs

So what do we do with this?

We do what we did last week.

We get specific.

We get small.

We get honest.

Last week, we named one piece of furniture in the house of the ego and committed to examining it.

This week, we move from the house to the body.

Mirza Maliki Tabrizi and Imam Khomeini have given us a map with three tiers.

Most of us live on Tier 1.

The work of this Ramadhan — the real work, the work that actually polishes the mirror — is to begin the serious, sustained effort of moving to Tier 2.

Not Tier 3.

Not yet.

The ego is not threatened by aspirations so grand they never materialise.

It is threatened by the small, specific, daily discipline that actually changes behaviour.

So here is the exercise for this week.

It is simple, and it is hard.

Pick one limb.

Not all of them.

Not a grand resolution to guard every part of your body from every sin.

That is the kind of commitment the ego loves — because it is so vast that it collapses under its own weight by Day 3, and then the ego says:

See? You cannot do this. Go back to just being hungry.

One limb.

One specific sin.

If it is the tongue — and for most of us, it is the tongue — then pick one thing.

Not

“I will stop all gossip.”

That is too big.

Pick:

I will not speak about any person who is not present in the room.

Or:

I will not complain about my spouse to my friends this week.

Or:

When I feel the urge to say something cutting, I will be silent for ten seconds and ask myself whether this is the fast speaking or the ego speaking.

If it is the eyes —

I will not scroll through my phone between Maghrib and Isha.

Or:

I will lower my gaze from one specific thing I know I should not be looking at.

If it is the ears —

I will leave the room when the conversation turns to gossip.

Or:

I will not listen to that podcast, that programme, that voice that fills my mind with noise and leaves no room for remembrance.

One limb.

One wall of the house, scrubbed clean this week.

Then next week, another.

This is how the mirror is polished.

Not in a single dramatic gesture, but in the slow, patient, daily friction of one corner at a time.

Until — and this is the promise that the tradition holds out to us — the reflection begins to appear.

Faintly at first.

A glimmer.

A moment in prayer where something shifts.

A moment at iftar where the food tastes different — not because the recipe changed, but because the tongue that cursed yesterday is learning to be still today.

A moment where you catch yourself about to say something cruel and you stop — and in that stopping, in that tiny, invisible act of restraint, you feel something you have not felt in years.

The mirror, working.

Light, reflected.

The fast, accepted.

How few are those who truly fast, and how many are those who are merely hungry.

Let us — this Ramadhan — be among the few.

Movement 3: The Outward Call — What Does a Clean Mirror Reflect?

A Mirror for Itself Is No Mirror at All

There is a temptation — and it is one of the subtlest traps on the spiritual path — to mistake self-purification for the goal.

You scrub the mirror.

You guard the tongue, the eyes, the hands.

You move from Tier 1 to Tier 2.

You begin to feel something — a lightness in prayer, a softness in the chest, a clarity that was not there before.

And then, almost imperceptibly, a new voice enters:

Look how clean I am becoming.

And the mirror, freshly polished, turns to face the wall.

Because a mirror that exists for itself — that admires its own cleanliness, that polishes itself to enjoy its own shine — has defeated its entire purpose.

A mirror exists to reflect.

A mirror exists to take light from one place and send it to another.

The moment it curves inward, gazing at its own surface, it becomes the most useless object in the room: a perfect reflector reflecting nothing.

Imam Khomeini saw this danger with devastating clarity.

In the same discussion of purification in Adab as-Salat, he warns that the spiritual wayfarer’s journey — even the act of purification itself — can become a trap if it is performed for the sake of the self:

«وإنّ منازل سير أهل الطريقة والسلوك إذا كانت لأجل الوصول إلى المقامات وحصول المعارج والمدارج فليست خارجةً عن تصرّف النفس والشيطان... والسيرُ في جوف البيت، ومثلُ هذا السالك ليس بمسافرٍ ولا سالك، وليس مهاجراً إلى الله ورسوله.»

“If the stations of the spiritual wayfarer’s journey are pursued for the sake of attaining ranks and ascending to degrees, then they have not escaped the dominion of the self and of Satan... Such a person is merely walking in circles inside the house. A wayfarer like this is neither a traveller nor a seeker — and he has not migrated to God and His Messenger.”

— Imam Khomeini, Adab as-Salat, Chapter on the Inner Disciplines of Removing Impurity

Walking in circles inside the house.

That is the image.

You can spend an entire Month of Ramadhan scrubbing, polishing, guarding every limb — and if all of it is oriented inward, toward your own spiritual status, toward the pleasure of your own progress, then you have not left the house.

You are not migrating.

You are redecorating.

The first session told us to leave the house of the ego.

This session has been about cleaning the mirror of the heart.

But now we must ask: cleaning it for what?

Polishing it toward whom?

The Light Must Go Somewhere

A polished mirror in a dark room is useless.

But a polished mirror in sunlight can illuminate an entire house — not by generating its own light, but by catching it and redirecting it to places it could not otherwise reach.

Into the corners.

Under the stairs.

Behind the door where someone is sitting in darkness, waiting.

This is the outward turn.

This is why the tradition never allows the inner work to remain inner.

Imam Khomeini, in the same passage, describes the ultimate purpose of purification — the qurb al-nawafil, the nearness of supererogatory worship — in terms that shatter any notion of private spirituality:

«فالسالك الكامل الواصل إذا خرج من بيت النفس المظلم وطوى عالم النفس بالكلّية... يتجلّى الحقّ تعالى في وجوده فيسمع بالحقّ ولا يسمع غير الحقّ ويبصر بالحقّ ولا يبصر سوى الحقّ ويبطش بالحقّ ولا يصدر منه إلّا الحقّ وينطق بالحقّ ولا ينطق إلّا الحقّ.»

“When the complete wayfarer who has arrived leaves the dark house of the self and folds up the world of the self entirely... the Truth — Exalted is He — manifests in his very existence. He hears through the Truth and hears nothing but the Truth. He sees through the Truth and sees nothing but the Truth. He grasps through the Truth and nothing issues from him except the Truth. He speaks through the Truth and speaks nothing but the Truth.”

— Imam Khomeini, Adab as-Salat, Chapter on the Three Purifications of the Awliya

This is not mystical abstraction.

This is a description of what happens when the mirror is clean and the light arrives.

The purified human being becomes a channel — not a container.

The eyes see truth; the tongue speaks truth; the hands act in truth.

The light enters and exits.

It passes through.

And where does it go?

It goes where it is needed most.

To the darkened corners of the world.

To the places where injustice has drawn the curtains and locked the doors.

The Mirror and the World

Here is where the fast must break through the walls of the prayer room and enter the street.

If your fast has truly moved from Tier 1 to Tier 2 — if your tongue is learning to be still, if your eyes are learning to lower, if your hands are learning restraint — then something has shifted inside you.

The mirror is less rusted than it was.

The reflection is beginning to appear.

But what does a clean mirror reflect?

It reflects whatever is in front of it.

And what is in front of us — right now, in this moment of history — is a world on fire.

Children in Gaza breaking their fast with nothing, their Ramadhan not a spiritual exercise but a siege.

Families in Sudan displaced from the very homes we spoke about leaving in Session 1 — except their displacement is not metaphorical.

Communities everywhere ground down by systems that hoard light and distribute darkness.

A polished heart cannot coexist with a silent tongue — not the silence of restraint we spoke about earlier, but the silence of complicity.

There is a fast of the tongue that is worship, and there is a silence of the tongue that is betrayal.

The tradition distinguishes sharply between the two.

The fast that guards the tongue from gossip must be the same fast that frees the tongue for truth.

The eyes that lower themselves from distraction must be the same eyes that refuse to look away from suffering.

The hands that refrain from taking what is not theirs must be the same hands that give what is needed, even when it costs.

This is not an addition to the fast.

This is not a bonus level for the especially devout.

This is the purpose of the purification.

Imam al-Sajjad, peace be upon him, in his supplication for the arrival of the Month of Ramadhan, makes this inseparable connection.

He does not pray for personal purification and then, separately, for social responsibility.

He weaves them into a single breath:

«وَوَفِّقْنَا فِيهِ لِأَنْ نَصِلَ أَرْحَامَنَا بِالْبِرِّ وَالصِّلَةِ، وَأَنْ نَتَعَاهَدَ جِيرَانَنَا بِالْإِفْضَالِ وَالْعَطِيَّةِ، وَأَنْ نُخَلِّصَ أَمْوَالَنَا مِنَ التَّبِعَاتِ، وَأَنْ نُطَهِّرَهَا بِإِخْرَاجِ الزَّكَوَاتِ، وَأَنْ نُرَاجِعَ مَنْ هَاجَرَنَا، وَأَنْ نُنْصِفَ مَنْ ظَلَمَنَا»

“Grant us success in this month to strengthen our bonds of kin with devotion and gifts, to attend to our neighbours with generosity and giving, to rid our possessions of all claims upon them, to purify them through paying what is due, to return to those who have turned away from us, and to deal justly with those who have wronged us.”

— Sahifa al-Sajjadiyyah, Supplication 44: Upon the Arrival of the Month of Ramadhan, Verse 9

Look at the movement in that single passage.

Strengthen kin.

Attend to neighbours.

Purify wealth.

Return to those who have left.

Do justice to those who have wronged you.

This is not a private du’a whispered in the corner of a dark room.

This is a social programme.

This is a manifesto for what a community of fasting people should look like when the mirror is working.

And notice —

to deal justly with those who have wronged us.

Not to forgive in a way that erases accountability.

Not to spiritualise injustice into a private lesson.

To do justice.

The Arabic is nunsifa — to give what is fair, to restore what has been taken, to make right what was made wrong.

The clean mirror does not look away from the world.

It looks into the world and reflects back the truth of what it sees — including the truth that demands action.

Your Light, Their Darkness

So the question this week is not only:

what limb are you guarding?

It is also:

where is your light going?

Who in your life is sitting in a dark corner, waiting for someone to redirect a little brightness their way?

Not grand charity.

Not the kind of giving that gets announced.

The quiet, specific, targeted act that only a clean mirror can see — because only a clear eye notices who has been overlooked.

The elderly neighbour who has no one to share iftar with.

The colleague at work who is struggling and has said nothing.

The family member you have not spoken to in months — or years — because of a wound that your ego refuses to release.

The causes that need your voice, your resources, your refusal to look away.

The Month of Ramadhan is not a retreat from the world.

It is a preparation for re-entry.

We fast, we clean, we polish — and then we turn.

Outward.

Toward the world that needs what we have been given.

A polished mirror that faces the wall is a tragedy.

A polished mirror that catches the light and sends it into the dark corners of the earth — that is worship.

That is the fast, complete.

Bridge to Session 3: The Feast of Light

We have, over these two sessions, done two things.

We left the house of the ego.

And we began to scrub the mirror of the heart — not just the surface dirt of daily living, but the deep rust of the limbs, the accumulated corrosion of a tongue unchained, of eyes unguarded, of hands undisciplined.

And now the mirror is cleaner — not spotless, not yet, perhaps not ever in this life — but cleaner.

Clearer.

Something is beginning to be reflected.

But here is the question that opens next week.

A clean mirror in a dark room reflects nothing.

An empty stomach that stays empty is not fasting — it is starvation.

The point of emptying was never the emptiness itself.

It was to make room.

Think about it.

We have spent this session talking about what the fast removes — the grime, the rust, the sins of the limbs.

But we have not yet asked:

what does the fast put in?

Because the tradition is very clear on this point:

God did not invite you to Ramadhan to starve.

He invited you to dine.

And the menu is not what you think.

Next week, we sit at God’s table.

We ask what the soul actually eats, why joy is the secret ingredient of worship, and what it means that the Prophet of God, peace be upon him and his family, described this month as — the Banquet of God.

If you have been thinking of the Month of Ramadhan as deprivation, next week will change that.

And next week brings something else — something the calendar has placed in our path with a precision that is not accidental.

Next week falls on the 10th of Ramadhan.

The day we mark the departure of Sayyedah Khadijah — the woman who understood the banquet before anyone else did.

The woman who took everything God gave her and fed it to the mission until there was nothing left.

We will sit at God’s table next week, and we will do so in the shadow of the woman who taught the entire Ummah what it means to give everything to the feast and keep nothing for yourself.

Come hungry.

A Ballad for the Rusted Mirror

In the voice of the one who has just seen the rust for the first time — and is asking, finally, for the polish.

O Light. O Most Holy.

O Beginning of all beginnings and End of all ends.

This is the du’a of the one who has looked into the mirror and flinched.

Imam Sajjad, peace be upon him, teaches us to ask — not in the language of the confident worshipper, but in the voice of the one who has just understood how deep the grime goes.

He prays for a fasting that reaches every limb:

«وَأَعِنَّا عَلَى صِيَامِهِ بِكَفِّ الْجَوَارِحِ عَنْ مَعَاصِيكَ، وَاسْتِعْمَالِهَا فِيهِ بِمَا يُرْضِيكَ، حَتَّى لَا نُصْغِيَ بِأَسْمَاعِنَا إِلَى لَغْوٍ، وَلَا نُسْرِعَ بِأَبْصَارِنَا إِلَى لَهْوٍ»

«وَحَتَّى لَا نَبْسُطَ أَيْدِيَنَا إِلَى مَحْظُورٍ، وَلَا نَخْطُوَ بِأَقْدَامِنَا إِلَى مَحْجُورٍ، وَحَتَّى لَا تَعِيَ بُطُونُنَا إِلَّا مَا أَحْلَلْتَ، وَلَا تَنْطِقَ أَلْسِنَتُنَا إِلَّا بِمَا مَثَّلْتَ»“Help us to fast in it by restraining our limbs from acts of disobedience toward You, and by employing them in that which pleases You — so that we lend not our ears to idle talk, nor hurry with our eyes toward diversion.”

“So that we stretch not our hands toward the forbidden, nor stride with our feet toward the prohibited — so that our bellies hold only what You have made lawful, and our tongues speak only what You have exemplified.”

— Sahifa al-Sajjadiyyah, Supplication 44, Verses 6–7

Every limb, named.

Every limb, surrendered.

This is the prayer of someone who has understood — really understood — that fasting is not about the stomach.

And in the deep night, when the limbs have been stilled and the mirror has been scrubbed and the rust has begun to lift — another voice rises.

Older.

Rawer.

The voice of the one who knows the names of his own sins:

«اللَّهُمَّ اغْفِرْ لِيَ الذُّنُوبَ الَّتِي تَهْتِكُ الْعِصَمَ» «اللَّهُمَّ اغْفِرْ لِيَ الذُّنُوبَ الَّتِي تُنْزِلُ النِّقَمَ» «اللَّهُمَّ اغْفِرْ لِيَ الذُّنُوبَ الَّتِي تُغَيِّرُ النِّعَمَ» «اللَّهُمَّ اغْفِرْ لِيَ الذُّنُوبَ الَّتِي تَحْبِسُ الدُّعَاءَ»

“O God, forgive me the sins that tear apart the veils of my honour.” “O God, forgive me the sins that bring down afflictions.” “O God, forgive me the sins that alter Your blessings.” “O God, forgive me the sins that hold back supplication.”

— Du’a Kumayl, Mafatih al-Jinan

The sins that hold back supplication.

Read that again.

There are sins so heavy, so calcified into the mirror, that they block even the asking.

You open your mouth to pray and the du’a cannot rise — not because God is not listening, but because the channel is clogged.

The rust is so thick that even the cry for help cannot get through.

This is why we fast.

This is why we scrub.

This is why we guard the limbs.

Not for the sake of discipline.

Not for the sake of spiritual achievement.

But because there are words we need to say to God — words the world needs us to say to God — and the rust is in the way.

So we scrub.

One limb at a time.

One corner of the mirror at a time.

Until the channel is clear enough for the voice to rise.

And when it does — when the du’a finally lifts, unobstructed, from a heart that has been scrubbed and a tongue that has been stilled and a body that has learned the difference between hunger and fasting —

This is what it says:

O God —

We come to You with mirrors so rusted we can barely find Your name in them.

We come to You with tongues that fasted from bread but feasted on cruelty, with eyes that lowered for no one, with hands that took and took and never opened.

We come to You in the month You called us to Your table and we are ashamed — because we spent the whole banquet hovering at the bread basket by the door.

O God —

By Muhammad, who was so full of Your Light that the world has not stopped reflecting him in fourteen hundred years.

By Khadijah, who took everything You gave her — her wealth, her standing, her comfort — and fed it to the da’wah until there was nothing left of her but faith.

She understood the banquet before anyone: that the food passes through you and becomes life for others.By Ali, who ate two loaves of barley and disciplined his soul until it came safely on the Day of the Great Fear.

By Fatimah, who hungered in this world so that the hungry of every world could eat.

By Hasan, Your Mujtaba — the Karim of the Ahl al-Bayt, who gave and gave and gave until generosity itself learned its name from him.

He did not hoard the Karamah.

He became it.By Husayn, who was denied even the water of the Euphrates — and whose thirst became the river from which every revolution of justice has drunk.

We ask You:

Do not leave us as we are.

We know why he is hidden from us. We know why the Imam of our age — Your proof, Your light, Your argument against us and for us — walks this earth and we cannot see him.

It is not because he has abandoned us. It is because our mirrors are too rusted to reflect him. It is because our eyes are too full of everything else to recognise him. It is because we have been so busy feeding the self that we have starved the only part of us that could bear his presence.

O God —

We are the reason for the longest night in history. We are the ones whose disobedience extends his absence, whose heedlessness thickens the veil, whose cruelty to each other makes us unworthy of the one who will fill the earth with justice as it has been filled with tyranny.

We know this.

And knowing it is not enough.

So we ask You — not from the station of the righteous, not from the station of the elite, not even from the station of the common believers — but from below all of that, from the floor, from the place where the only honest prayer left is:

Help.

Help us become worthy of him. Help us scrub this mirror — limb by limb, sin by sin, day by day — until something of his light can be reflected in us. Help us move from the fasting of the hungry to the fasting of the watchful, and from the fasting of the watchful to the fasting of the broken-open — those who have nothing left in them but You.

Give us the strength to guard one limb tomorrow that we did not guard today. Give us the courage to speak one truth this week that our silence has been burying. Give us the ache — the blessed, unbearable ache — of missing someone we have never met but whose return depends on whether we change.

O God —

For his sake, do not let this Month of Ramadhan pass the way the others have passed — with nothing cleaned, nothing polished, nothing changed.

For his sake, make us among the few who truly fast and not among the many who are merely hungry.

For his sake — and for the sake of every soul that is waiting in the dark for a window to let the light in —

Polish us. Break us open if You must. But do not leave us as we are.

«اللَّهُمَّ صَلِّ عَلَى مُحَمَّدٍ وَآلِهِ، وَامْحَقْ ذُنُوبَنَا مَعَ امِّحَاقِ هِلَالِهِ، وَاسْلَخْ عَنَّا تَبِعَاتِنَا مَعَ انْسِلَاخِ أَيَّامِهِ حَتَّى يَنْقَضِيَ عَنَّا وَقَدْ صَفَّيْتَنَا فِيهِ مِنَ الْخَطِيئَاتِ، وَأَخْلَصْتَنَا فِيهِ مِنَ السَّيِّئَاتِ»

O God, efface our sins along with the effacing of its crescent moon, and make us pass forth from the ill effects of our acts with the passing of its days, until it leaves us behind — while within it You have purified us of offences and rid us of evil deeds.

— Sahifa al-Sajjadiyyah, Supplication 44, Verse 14

اللَّهُمَّ صَلِّ عَلَى مُحَمَّدٍ وَآلِ مُحَمَّدٍ وَعَجِّلْ فَرَجَهُمْ

O God, send Your blessings upon Muhammad and the Family of Muhammad, and hasten their relief.

Amen, O Lord Sustainer of the Universes.

Amen, O Most Merciful of the Merciful.

And from Him alone is all ability, and He has authority over all things.