[2] Wilayah in the Home - The Unfolding Tapestry: Weaving a Life of Love and Purpose

Wilayah in the Home: A Fatimiyyah Series on Marriage and Family, based on the Quran, the Tradition of the Ahlulbayt, and guidance drawn from the teachings of Imam Khamenei. Fatimiyyah 2025/1447

In His Name, the Most High

This is session two in our three-part Fatimiyyah 2025/1447 series, “Wilayah in the Home,” focusing on Marriage and Family, based on the Quran, the Tradition of the Ahlulbayt (peace be upon them), and guidance drawn from the teachings of Imam Khamenei.

As with our explorations into subjects like The Art of Supplication, The Lantern of the Path or the Tabyeen series (for Ashura and Arbaeen 2025/1447), it is strongly recommended that readers engage with the previous session prior to consuming the current one.

This is due to the cumulative nature of our discussion; the manner of discourse requires that each part build upon foundations laid in the ones that came before.

Proceeding sequentially helps avoid confusion, misunderstanding, or invalid assumptions, ensuring we move towards clarity on these vital matters.

While this session will include a brief recap, it is highly summarised.

To grasp the full context and nuance of our first session on establishing the foundations, engaging with, studying, and reflecting upon it is essential.

Therefore, while these discussions might sometimes feel detailed or lengthy, the subject matter is profoundly important. We request patience and encourage everyone to read through to the end, following the progression of the series for maximum benefit.

God willing, this journey will illuminate the path towards building stronger, tawheed-centric, faith-centred families.

Video of the Majlis (Sermon)

This is the video of the majlis (sermon)

Audio of the Majlis (Sermon)

This is the audio of the majlis (sermon)

Recap

The First Stitch: Weaving Faith into Marriage

In our first session, we focused on the essential foundations required before the marital union is formally established. We began by framing marriage not as a mere social contract, but as a profound, sacred covenant (mithaq ghalidh) ordained by God.

We explored how this union is built upon the divine gifts of tranquility (sakinah), affection (mawaddah), and mercy (rahmah), establishing God as the “unseen third” and central reality of the relationship.

From this spiritual blueprint, we examined the critical process of spousal selection, emphasising the primacy of deen (faith) and akhlaq (character) over all worldly or cultural filters.

We presented robust evidence from the Quran, the Imams (peace be upon them), and contemporary scholars like Ayatullah Sistani and Imam Khomeini (may God be pleased with them) to dismantle un-Islamic, Jahili customs such as lineage exclusivity (e.g., “Sayyed-only” marriages) and, unequivocally, the haram (forbidden) nature of forced marriage.

We then embraced the sunnah of simplicity, using the marriage of Sayyedah Fatimah (peace be upon her) as our model to critique the modern burdens of excessive mahr and competitive jahazieh (trousseau), identifying them as practices that commodify the relationship and create societal barriers.

Finally, we addressed the external distortions from media, materialism, and pornography that create false expectations, and clarified the wisdom of timely marriage.

This included a necessary tabyeen (clarification) on temporary marriage (mut’ah), affirming its specific fiqhi basis and hikmah (wisdom) as a “safety valve” (as explained by Shaheed Ayatullah Mutahhari) while simultaneously condemning its misuse for casual encounters, which stands in stark opposition to the foundational goal of building stable, committed families.

Having laid these essential foundations—clarifying our intention, our selection criteria, and our understanding of the commitment—we now move from the preparation for marriage to the practice of marriage.

If our first session was about weaving the “first stitch” correctly, setting the foundational threads upon the loom of faith, the second session - this session — “The Unfolding Tapestry: Weaving a Life of Love and Purpose” — is about the intricate process of weaving that follows.

We move from the blueprint to the creation; from the covenant to the cultivation of the tapestry itself.

Now that the loom is set and the first threads are secure, how do we weave the complex patterns of love, responsibility, and shared life?

How do we introduce the vibrant colours of mawaddah and rahmah and ensure the sakinah remains the backdrop?

How do we navigate the tensions of the threads—the roles, responsibilities, and inevitable conflicts—to create a beautiful, cohesive, and strong fabric, ensuring the family becomes a testament to faith and a true manifestation of Wilayah?

Wilayah in the Home - The Unfolding Tapestry: Weaving a Life of Love and Purpose

The Binding Threads: Nurturing Mawaddah, Rahmah, and Trust

In our first session, we established that God Himself places mawaddah (affection) and rahmah (mercy) between spouses.

These are the divine threads from which the tapestry of marriage is woven.

However, these gifts are not static.

A tapestry does not weave itself.

These threads require active, continuous, and skilful cultivation.

The “unfolding tapestry” of a shared life is a work of constant, conscious effort.

Deconstructing Love: Mawaddah vs. “Hollywood”

The first distortion we must address is the very definition of love.

We live immersed in a culture (from Hollywood, Bollywood, social media, etc.) that relentlessly promotes a superficial, emotion-based concept of love.

This “love” is about grand gestures, “flowers and chocolates,” constant romantic highs, and finding a “soulmate” who effortlessly completes us.

This is not mawaddah; this is a fading print on the fabric, not the thread itself.

When the print fades—as it inevitably does when the realities of life, bills, and differing opinions set in—people believe the love is “gone” and the marriage has failed.

Islamic mawaddah is far deeper. It is an “active verb,”.

It is a commitment.

It is the hard work of kindness, appreciation, sacrifice, and forgiveness, especially when the fleeting feelings of passion are low.

This is the “cement” Imam Khamenei speaks of:

محبت آن ملاطی است که اینها را برای هم حفظ میکند... محبت که بود، وفاداری هم هست.

Love is the cement... that holds these [the spouses] together for each other... When there is love, there is also faithfulness.

— Imam Khamenei, Zan va Khanevadeh (Woman and Family), Page 137

True love is not just a feeling; it is a decision to care for the other’s well-being and spiritual journey.

Ayatullah Shaheed Murtadha Mutahhari explains that Islamic marriage is based on a higher “uniting” factor than mere passionate love, which can be blind.

It is based on a shared spiritual direction and purpose.

When love is rooted in this shared journey towards God, it is sustainable. When it is rooted only in passion or worldly benefits, it is as unstable as its foundation.

عشق و علاقه ی ناشی از هماهنگی روحانی و اخلاقی، یا ناشی از هم فکری و هم عقیدگی، و یا ناشی از کمال و جمال و هنر و فضیلت محبوب، و یا ناشی از احسان و خدمت او، امری است که قابل اعتماد است و می تواند کانون خانواده را گرم نگه دارد... اما عشقهای جنسی زودگذر است، همان طور که به سرعت پیدا می شود به سرعت هم خاموش می شود. این گونه عشقها نمی تواند پایه ی اساسی ازدواج باشد.

“Love and affection arising from spiritual and ethical harmony, or arising from shared thought and shared belief, or arising from the perfection, beauty, art, and virtue of the beloved, or arising from their goodness and service, is a matter that is reliable and can keep the hearth of the family warm... But sexual, passionate loves (ishq-ha-ye jinsi) are fleeting; just as they appear quickly, they are extinguished quickly. Such loves cannot be the fundamental basis for marriage.”

—Ayatullah Murtadha Mutahhari, Mas’ale-ye Hijab (The Issue of Hijab), Page 88

The Soil of Love: Trust as a Two-Way Street

This profound mawaddah can only grow in the soil of mutual trust.

Without trust, the threads rot.

God warns us in the Holy Quran about the destructive nature of baseless suspicion (su’ al-dhann):

يَا أَيُّهَا الَّذِينَ آمَنُوا اجْتَنِبُوا كَثِيرًا مِّنَ الظَّنِّ إِنَّ بَعْضَ الظَّنِّ إِثْمٌ...

O you who have faith! Avoid much suspicion; indeed some suspicions are a sin...

— Qur’an, Surah al-Hujurat (the Chapter of the Chambers) #49, Verse 12

However, this is not a one-way street.

This sacred injunction against feeling suspicion cannot be used as a shield by a spouse who is actively causing suspicion.

Islam also commands us to be trustworthy and transparent.

Imam Ali (peace be upon him) warned:

...إِيَّاكَ وَ مَوَاطِنَ التُّهَمَةِ...

...Beware of the positions of accusation...

—Nahjul Balagha, Letter 53

While this was advice to a governor, the principle is universal:

Do not put yourself in suspicious situations that invite others to think ill of you.

A spouse who is secretive with their phone, maintains inappropriate “friendships,” or is dishonest about their whereabouts is creating a fracture in the tapestry.

They cannot then blame their partner for feeling suspicious.

When doubt or suspicion does arise, it must be addressed.

Silently “sewing over” the fracture, does not heal it; it leaves a permanent weakness.

The couple must engage in respectful, open dialogue.

This is where secular research, such as the work of Dr. John Gottman, aligns with Islamic principles. His extensive research, outlined in the “Sound Relationship House” model, identifies Trust and Commitment as the two load-bearing walls that hold the entire structure of a healthy relationship together.

While other elements like fondness and managing conflict form the floors, without the stability provided by these two walls, the house cannot stand.

“Trust is built in very small moments, which I call ‘sliding door’ moments... In any interaction, there is a possibility of connecting with your partner or turning away from your partner. One such moment is not important, but if you’re always choosing to turn away, then trust erodes in a relationship—very gradually, very slowly.”

— John Gottman, Ph.D. The Science of Trust: Emotional Attunement for Couples. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2011

When doubt or suspicion does arise, it must be addressed.

Silently “sewing over” the fracture, does not heal it; it leaves a permanent weakness.

The couple must engage in respectful, open dialogue.

Ignoring a partner’s genuine fears, dismissing them by quoting the ayah on suspicion, or refusing to be transparent (thereby failing to build trust in these “sliding door” moments) is an act of emotional manipulation that shatters trust.

True rahmah (mercy) involves giving your spouse the reassurance they need, and true taqwa (piety) involves living a life of such clarity that suspicion cannot find fertile ground.

The Sacred Garment: Concealment and Its Limits

This profound bond of love and trust is captured in one of the most beautiful metaphors for marriage in the Holy Quran: spouses as garments (libas) for one another.

...هُنَّ لِبَاسٌ لَّكُمْ وَأَنتُمْ لِبَاسٌ لَّهُنَّ…

...They are a garment for you, and you are a garment for them...

— Qur’an, Surah al-Baqarah (the Chapter of the Cow) #2, Verse 187

A garment serves three essential functions, and so must a spouse:

Protection: A garment protects us from the elements. Spouses must protect each other from sin, hardship, despair, and external attacks on their dignity.

Adornment (Zeena): A garment beautifies us. Spouses must be a source of adornment for each other, elevating their character and piety, not a source of shame.

Concealment (Satr): A garment conceals our physical flaws. Spouses have a profound duty to conceal each other’s inner faults, weaknesses, and private mistakes from the world.

Exposing a spouse’s faults to family or friends is a betrayal of this sacred trust.

It is, as Imam Khamenei notes, the opposite of what a Libas does.

لباس هم انسان را حفظ میکند، هم انسان را زیبا میکند، هم عیوب او را میپوشاند... زن و شوهر باید نسبت به هم اینجور باشند: همدیگر را حفظ کنند؛ عیوب هم را بپوشانند؛ همدیگر را زیبا کنند، یعنی همدیگر را آراسته کنند.

A garment both protects a person, beautifies a person, and covers their faults... A husband and wife must be this way for each other: protect each other; cover each other’s faults; beautify each other, meaning adorn one another [in character and appearance].

— Paraphrased from Imam Khamenei’s consistent teachings on the ‘Libas’ verse

Here, we must apply critical tabyeen (clarification).

This sacred duty of concealment is not a mandate for silent suffering, nor does it mean enabling sin or dysfunction. There is a profound difference between destructive gossip (ghibah) and constructive consultation (istisharah).

To complain idly about a spouse’s faults (e.g., habits, minor failings) to friends or family simply to vent, backbite, or diminish them is a grave sin and a clear betrayal of the libas trust.

However, the Quran itself provides the exception.

While God commands us to avoid publicising evil, He makes a clear exception for the one who has been wronged:

لَّا يُحِبُّ اللَّهُ الْجَهْرَ بِالسُّوءِ مِنَ الْقَوْلِ إِلَّا مَن ظُلِمَ وَكَانَ اللَّهُ سَمِيعًا عَلِيمًا

God does not love the public utterance of evil speech, except by one who has been wronged (illa man dhulim). And God is Ever-Hearing, All-Knowing.

— Qur’an, Surah al-Nisa (the Chapter of the Women) #4, Verse 148

The one who is oppressed (madhlum) is given a divine license to speak.

This verse is the foundational proof that “concealment” does not apply to “oppression” (dhulm).

Furthermore, Islamic jurisprudence (fiqh) explicitly lists exceptions to the prohibition of backbiting (ghibah).

It is not a sin to speak of another’s fault if it is for a legitimate, overriding purpose. Ayatullah Sistani, echoing the consensus of senior scholars, outlines these exceptions:

المسألة ٢٦: تجوز الغيبة في موارد:

١ ـ تظلّم المظلوم أمام من يُرجى منه إنصافه من الظالم، بجواز أن يذكر للغير ما جرى عليه من الظلم من دون قصد الاستعانة منه على رفعه.

٢ ـ نصح المستشير في أمر كالزواج أو المعاملة أو نحو ذلك، فيجوز ذكر ما يوجب النقص في المشهود عليه.

٣ ـ جرح الشاهد والراوي.

٤ ـ استشارة الناصح في أن المستشار منه هل هو أهل لعمل معيّن.

٥ ـ النهي عن المنكر فيما إذا توقّف على الغيبة.

٦ ـ غيبة المتجاهر بالفسق، ويختصّ جوازها بما تجاهر به.

٧ ـ القدح في المقالات الباطلة.

٨ ـ الشهادة أمام الحاكم.

٩ ـ دفع الضرر عن المُغتاب.

١٠ ـ أن يكون الغرض من الغيبة عنواناً راجحاً أهمّ من مفسدة الغيبة، كما إذا كان لغرض كشف مؤامرة خطيرة على الإسلام والمسلمين.Issue 26: Ghibah (backbiting) is permissible in certain instances:

1 - The complaint of one who is oppressed (tadhallum al-madhlum) before one from whom he hopes to get justice from the oppressor...

2 - Advising one who seeks counsel (nash al-mustashir) in a matter like marriage or a transaction... it is permissible to mention what constitutes a defect in the one being discussed...

3 - Discrediting a witness or narrator.

4 - Consulting a sincere advisor (istisharat al-nasih) on whether the person being consulted about is suitable for a specific task...

5 - Forbidding an evil (al-nahy ‘an al-munkar), when it depends upon backbiting.

6 - Backbiting one who openly commits sin (al-mutajahir bil-fisq), but this is limited only to the sin he commits openly...

7 - Criticising false ideologies...

8 - Testifying before a judge...

9 - Repelling harm from the one being backbitten...

10 - When the purpose of the backbiting is for a greater overriding good which is more important than the corruption of backbiting, such as exposing a dangerous conspiracy against Islam and the Muslims.— Ayatullah Sistani, Minhaj al-Salihin, Vol. 2, Book of Makasib, Issue 26

This ruling provides the exact tabyeen we need.

Seeking Redress (Tadhallum): If one spouse is oppressing the other (abuse, denial of rights), the oppressed spouse is permitted to speak to an authority (a scholar, judge, or elder) who has the power to stop the oppression. This is not sinful; it is seeking justice.

Seeking Consultation (Istisharah): If one spouse has a persistent, harmful fault (e.g., addiction, severe anger, neglect of religion), the other spouse is permitted to disclose the problem—delicately and only to the extent necessary—to a qualified person (a therapist, doctor, or trusted religious mentor) specifically to seek a solution (‘ilāj).

Therefore, we must address the guilt that many (especially women) feel when “complaining.” If the “complaint” is idle gossip, the guilt is justified. But if the “complaint” is actually a plea for help, a tadhallum, or an istisharah intended to fix a damaging problem, there should be no guilt.

This desire to mend the relationship, to “wash the linen to make it beautiful,” is not a failure or a betrayal. It is, in fact, an act of great honour and the deepest manifestation of mawaddah. It signifies a profound care for the health of the marriage and, just as importantly, for the spiritual well-being of the spouse who is committing the fault or the sin.

It is an attempt to save them and the family, which is the highest form of spousal support and an embodiment of the Quranic principle:

...وَتَعَاوَنُوا عَلَى الْبِرِّ وَالتَّقْوَىٰ وَلَا تَعَاوَنُوا عَلَى الْإِثْمِ وَالْعُدْوَانِ...

...Cooperate in righteousness and piety (taqwa), but do not cooperate in sin and aggression...

— Qur’an, Surah al-Ma’idah (the Chapter of the Table Spread) #5, Verse 2

Silently enduring abuse or destructive sin is a form of cooperation in sin.

Seeking a remedy is cooperation in birr (righteousness) and taqwa.

The Tear in the Tapestry: When Concealment is Not Required

This brings us to the most critical distinction: the duty to conceal “faults” (‘uyub) absolutely does not apply to “oppression” (dhulm) or “harm” (dharar).

A “fault” is a personal weakness, a “loose thread” — laziness, a short temper, a bad habit.

An “abuse” is dhulm (oppression), a “tear in the tapestry” — physical violence, patterns of verbal degradation, psychological manipulation, financial exploitation, or deliberate and harmful negligence (whether from the spouse or their family).

Concealing dhulm is not piety; it is enabling sin.

A spouse’s role as libas is to protect their partner.

If a husband is harming his wife (or vice versa), he has violated his role as a libas.

Her first duty is to her own safety and faith, not to concealing his crimes.

The Prophet (peace and blessings be upon him and his family) said

خَيْرُكُمْ خَيْرُكُمْ لِأَهْلِهِ، وَأَنَا خَيْرُكُمْ لِأَهْلِي

“The best of you is the best to his family, and I am the best of you to my family.”

— Al-Tusi, Al-Amali

This “bestness” is the antithesis of abuse.

The confusion over roles is often used to justify harm, but Islamic teachings, when understood correctly, prevent this.

The hadith from Imam Ali (peace be upon him) regarding the wife’s role, as explained by Imam Khamenei, is a foundational principle of this protection.

It clarifies the relationship is one of love and cherishing, not dominance and servitude.

«إنّما المرأة ریحانة و لیست بقهرمانة»... زن گل است... نوع برخورد با گل چگونه است؟... قهرمان... یعنی مباشر امور... سرکارگر. یعنی در خانه ی شما زن را بعنوان مباشر امور خودتان ندانید.

“A woman is a flower (rayhanah), not a chambermaid (qahramanah)”... A woman is a flower. How does one interact with a flower?... qahramanah... means a manager of affairs... a foreman. Meaning, do not consider the woman in your house as your manager of affairs.

— Imam Khamenei, Zan va Khanevadeh (Woman and Family), Page 60

This distinction is the key.

While the hadith warns against treating the wife as a qahramanah (a foreman or servant), this does not negate her foundational role as the honoured internal manager of the household.

In fact, Imam Khamenei explicitly affirms this positive managerial role, using terms like modir (manager) and kadbanoo (lady of the house).

تدبیر، مدیریت، ظرافت؛ کار کدبانوی خانواده

Prudence, management (modiriyyat), [and] finesse; [this is] the work of the lady of the house (kadbanoo).

— Imam Khamenei, Zan va Khanevadeh (Woman and Family), Page 58

He further defines this role as one of honoured oversight and authority:

...آن کسی که اداره میکند، کدبانو یعنی آن کسی که محیط خانواده تحت اشراف اوست تحت نظارت و تدبیر و مدیریت اوست...

...the one who administers, the lady of the house (kadbanoo), means the one under whose supervision, oversight, prudence, and management (modiriyyat) the family environment is...

— Imam Khamenei, Zan va Khanevadeh (Woman and Family), Page 50

Thus, the hadith (”She is a flower, not a foreman”) is forbidding a dynamic of servile management, where the husband treats his wife as an employee to be ordered around.

It is affirming her role as an honoured partner and internal director, who manages with finesse and must be treated with the care due to a cherished rayhanah.

Therefore, any act of abuse (physical, verbal, or emotional) is a direct violation of the husband’s duty as protector and a gross misunderstanding of his role.

One does not crush a flower.

One does not scream at a flower.

One does not abuse the manager of one’s home.

If the tapestry is being torn by such oppression, it is not a “fault” to be hidden under the guise of libas; it is a grave harm that must be urgently mended, which often requires seeking external help (from elders, scholars, or authorities) as we will discuss in the next session, God willing.

Lessons for the Present: Love as Active, Trust as Earned, Safety as Non-Negotiable

This understanding demands we mature our view of love.

True mawaddah is not the “honeymoon period”; it is the daily, hard work of watering the plant, pulling the weeds, and protecting it.

It is the commitment to be kind even when tired, to be forgiving even when hurt, and to prioritise the relationship’s health over one’s own ego.

Trust must be treated as a “two-way pathway.”

We must avoid suspicion (as the Quran commands), but we must also live a transparent life that earns trust and starves suspicion (as the hadith guides).

If genuine doubt arises, it must be addressed through compassionate, respectful dialogue, not accusations or defensive dismissals.

Finally, we must internalise the limits of “concealment.”

Our duty as a libas is to protect our spouse, especially their dignity. But this never means concealing or enabling abuse (physical, emotional, or psychological).

A home where dhulm (oppression) exists is not a manifestation of wilayah and is not protected by a duty of silence.

Seeking help to remedy a serious fault is honourable, and seeking help to stop abuse is a non-negotiable obligation.

Call to Clarify: Defining True Love, Trust, and Safety

We must ask ourselves and clarify for our communities:

Are we promoting the sustainable, active mawaddah of the Quran, or the unsustainable, feeling-based “love” of Hollywood?

Let us clarify that true love is an active verb and a deep commitment.

We must clarify that trust is a two-way responsibility.

While we must avoid baseless suspicion (su’ al-dhann), we must also clarify the grave sin of causing suspicion through secretive or inappropriate behaviour.

Clarify that using the prohibition of suspicion as a shield to deflect legitimate concerns is a form of manipulation.

Most critically, we must clarify the non-negotiable line between “faults” and “abuse.”

Let us clarify to our sisters and brothers that “concealing faults” (satr al-’uyub) never means enduring oppression (dhulm).

Clarify that Islam guarantees safety and dignity (karamah) in marriage and that seeking help to stop abuse—tadhallum—is a Quranic right.

And let us clarify that seeking professional or scholarly help to remedy a serious fault—istisharah—is not an act of guilt, but an act of honour and a true sign of commitment to mending the tapestry.

The Divine Pattern: Understanding Qawwam and Rayhanah

As we weave the tapestry of married life, we must understand the divine pattern for the threads of responsibility.

The relationship between husband and wife in Islam is one of profound partnership, mutual respect, and complementary roles.

It is not a relationship of hierarchy in the worldly sense of a “boss” and “employee,” nor is it an undefined arrangement without structure.

God, in His infinite wisdom, has assigned distinct, nature-based roles that ensure the stability, protection, and flourishing of the family unit.

Unpacking Qawwam: Leadership as Responsibility, Not Tyranny

The Holy Quran introduces the concept of Qawwam in relation to men:

الرِّجَالُ قَوَّامُونَ عَلَى النِّسَاءِ بِمَا فَضَّلَ اللَّهُ بَعْضَهُمْ عَلَىٰ بَعْضٍ وَبِمَا أَنفَقُوا مِنْ أَمْوَالِهِمْ...

Men are the protectors and maintainers (qawwamuna) of women, because God has given the one more [strength] than the other, and because they support them from their means...

— Qur’an, Surah al-Nisa (the Chapter of the Women) #4, Verse 34

This verse has often been misunderstood and misused to justify authoritarianism or domination.

However, qawwam does not mean “dictator” or “tyrant.”

It signifies management, protection, maintenance, and responsibility.

Imam Khamenei clarifies that this role is tied directly to the specific characteristics God has given man, making him more suited for the external struggles and protection of the family unit.

«الرِّجَالُ قَوَّامُونَ عَلَى النِّسَاءِ»... يعنى سرپرستى امور خانواده به عهدهى مرد است... اين هم به خاطر خصوصياتى است كه در مرد و زن هست... مسئلهى تأمین معیشت خانواده، این از نظر اسلام مربوط به مرد است.

“Men are the protectors and maintainers (qawwamuna) of women”... meaning the supervision/management of the family’s affairs is the responsibility of the man... This is also because of the specific characteristics that exist in men and women... The issue of providing for the family’s livelihood, this is the man’s responsibility from Islam’s perspective.

— Imam Khamenei, Zan va Khanevadeh (Woman and Family), Page 71, 119

This role of qawwam is a heavy responsibility, not a privilege of power.

It obligates the man to be the family’s primary protector from external harms (physical, financial, ideological) and its primary provider.

His “leadership” is one of service, justice (‘adalah), and kindness (ihsan).

He is the “fortress” and “stronghold” that provides the security for the wife to fulfil her central role.

Imam Khamenei notes that this does not give the man absolute authority in all matters.

«الرِّجَالُ قَوَّامُونَ عَلَى النِّسَاءِ»... این به معنای این نیست که زن بایست در همهی امور تابع شوهر باشد؛ نه... فقط در بعضی از موارد است.

“Men are the protectors and maintainers (qawwamuna) of women”... This does not mean that the wife must be subordinate to the husband in all affairs; no... It is only in certain matters.

— Imam Khamenei, Zan va Khanevadeh (Woman and Family), Page 123

His authority is linked to the overall management and protection of the family unit.

It is not an authority over her personal property, her personal beliefs, her relationship with her own family, or her independent thoughts.

So, what are these “certain matters”?

Islamic jurisprudence (fiqh) is very specific here.

The “matters” where a husband’s permission is traditionally required are primarily two:

Matters of Intimacy (tamkin): The wife is expected to be responsive to her husband’s need for sexual intimacy, just as he is expected to fulfil his duties towards her. (This, of course, does not apply during states of religious prohibition like menstruation, or states of harm (dharar) or illness).

Leaving the House: The wife traditionally requires the husband’s permission to exit the home.

However—and this is the critical tabyeen (clarification) to prevent misuse—this rule is not absolute.

It is qualified by justice, necessity, and prior agreements.

The right of the husband to qawwam (maintenance) is tied to his fulfilment of duties, and his authority to grant permission for leaving the house is not a tool for oppression, isolation, or control.

Ayatullah Sistani provides a comprehensive clarification on this matter, which outlines the rule and its crucial exceptions:

السؤال: هل للمرأة الخروج من البيت دون إذن زوجها؟

الجواب: يجب على الزوجة أن تمكّن زوجها من نفسها متى شاء... ويحرم عليها الخروج من بيتها من دون إذنه إذا كان ذلك منافياً لحقّه في الاستمتاع بها بل مطلقاً على الأحوط لزوماً، إلاّ أن يكون الخروج لأداء واجب كالحج الواجب أو لضرورة تقتضي خروجها كالعلاج أو توقف تحصيل علم واجب عليها على الخروج أو كان الخروج لغاية راجحة دينية أو دنيوية ولم يكن الزوج قادراً على إيصالها إلى غايتها.

Question: Can a woman leave the house without her husband’s permission?

Answer: The wife must make herself available (tamkin) to her husband for intimacy whenever he wishes... and it is forbidden for her to leave her house without his permission if it conflicts with his right to intimacy... rather, based on obligatory precaution (al-ahwat luzuman), [she should not exit] without his permission at all. Except if the exit is for performing an obligation (wajib), like the obligatory Hajj, or for a necessity (dharurah) that requires her exit, like medical treatment, or if acquiring obligatory knowledge depends on her exiting, or if the exit is for a superior religious or worldly purpose and the husband is not capable of facilitating that goal for her.

— Ayatullah Sistani, sistani.org, Q&A Section, Fiqh for Women, Marriage Questions, Question #12 - paraphrased/compiled ruling)

This clarification is vital.

The husband’s authority is not a tool for abuse.

The wife retains her right—and in fact, has an obligation—to leave the house for her own obligatory duties (like Hajj, seeking essential medical care, or acquiring necessary religious knowledge) and even, in some views, for rational and necessary worldly matters if he cannot provide them.

Furthermore, all of these conditions are negotiable before marriage through stipulations in the marriage contract (shurut dimn al-’aqd).

A woman can lawfully stipulate her right to work, to study, or to visit her family, and these conditions become binding upon the husband.

It is vital to understand that this fiqhi framework, with its rules and exceptions, is not intended to create a legalistic or adversarial home.

The entire goal of the Islamic marriage, as we established, is to foster sakinah, mawaddah, and rahmah.

In a healthy, functioning Islamic marriage built on these principles, these specific permissions rarely, if ever, become a “bone of contention.”

Communication and consultation are natural.

A wife who respects the partnership will naturally communicate her plans, and a husband who truly embodies his role as a protector (not a controller) and loves his wife as a rayhanah (cherished flower) would not be unreasonable, forbidding her, for example, from visiting her family or going shopping without a valid, shar’i reason.

These rules are a structural safeguard for the family unit, not a tool for one spouse to exert arbitrary control over the other.

The spirit of the law is mutual respect and cooperation, not “patriarchal empowerment.”

A home built on unreasonable restrictions is the very opposite of sakinah.

His authority is linked to his primary responsibilities and is heavily qualified to prevent dhulm (abuse).

Understanding Rayhanah: Honour as Partner, Not Servitude

Complementing the man’s external role is the woman’s central, internal role, which is defined not by servitude but by honour.

The tradition from Imam Ali (peace be upon him), which we introduced in the first point, is the key to this understanding.

«إنّما المرأة ریحانة و لیست بقهرمانة»... زن گل است... نوع برخورد با گل چگونه است؟... قهرمان... یعنی مباشر امور... سرکارگر. یعنی در خانه ی شما زن را بعنوان مباشر امور خودتان ندانید.

“A woman is a flower (rayhanah), not a chambermaid (qahramanah)”... A woman is a flower. How does one interact with a flower?... qahramanah... means a manager of affairs... a foreman. Meaning, do not consider the woman in your house as your manager of affairs.

— Imam Khamenei, Zan va Khanevadeh (Woman and Family), Page 60

This hadith is a profound clarification.

It rejects a model where the wife is a qahramanah—a foreman, servant, or employee who simply takes orders. Treating her as such is forbidden and is within the realm of dhulm (oppression).

Rather, she is a rayhanah—a cherished flower, the source of beauty, tranquility (sakinah), and affection in the home.

This does not mean she is without a role.

As we clarified, Imam Khamenei affirms her role as the honoured internal manager (modir or kadbanoo).

...آن کسی که اداره میکند، کدبانو یعنی آن کسی که محیط خانواده تحت اشراف اوست تحت نظارت و تدبیر و مدیریت اوست...

...the one who administers, the lady of the house (kadbanoo), means the one under whose supervision, oversight, prudence, and management (modiriyyat) the family environment is...

— Imam Khamenei, Zan va Khanevadeh (Woman and Family), Page 50

The Divine Pattern is this:

The husband is the External Manager (qawwam), providing security and resources.

The wife is the Internal Manager (modir), cultivating the home environment with her mawaddah, rahmah, and prudence (tadbir).

He is the fortress; she is the garden within.

He provides the “what” (resources); she manages the “how” (the home’s atmosphere, tarbiyyah, and inner life).

This is a partnership of Wilayah, not a hierarchy of domination.

Lessons for the Present: Living the Roles with Justice and Mercy

This Islamic model demands a re-education for both men and women.

For men, being qawwam is a test of responsibility.

It means providing financially without acting like a dictator, and protecting the family (including the wife from one’s own anger or the harm of one’s own family) without being controlling.

It requires sacrificing one’s ego for the well-being of the home.

A man who uses this verse to justify shouting, demanding service, or belittling his wife has failed the test of being qawwam and is committing dhulm - a terrible crime and sin.

For women, understanding the role of rayhanah and kadbanoo is a source of honour, not weakness.

It affirms that the finesse, prudence, and compassion she brings to the home are her unique strengths and her primary domain of authority.

It is her management and her affection that transforms a mere house into a home filled with sakinah.

It is a role of active leadership, not passive servitude.

Both roles are essential, complementary, and, in God’s sight, equal in value.

Call to Clarify: Rescuing Roles from Cultural Distortion

We must ask ourselves and clarify for our communities:

What is the true meaning of qawwam?

Let us clarify that it means responsibility for protection and provision, not a license for domination, control, or abuse.

We must clarify that a man who harms his wife, either physically, verbally, or emotionally, has failed in his primary duty as qawwam and stands accountable before God as an oppressor.

We must also clarify:

What is the true meaning of rayhanah?

Let us clarify that it signifies honour, respect, and cherished partnership.

It is the antithesis of being a servant (qahramanah).

We must clarify that the wife’s role as the modir (Internal Manager) of the home is a position of authority and profound importance, essential for the family’s spiritual and emotional well-being.

By clarifying these balanced and just roles, we can dismantle both the oppressive cultural models of patriarchy and the reactive secular models that seek to erase the beautiful, complementary nature designed by God.

The Balanced Weave: Home, Faith, and Society

Understanding the divine pattern of roles as a partnership of qawwam (protector/provider) and rayhanah (cherished/manager) brings us to one of the most pressing questions in modern life:

How do we weave the threads of family responsibility with the threads of education, career, and social participation, especially for women?

We are often presented with a false and damaging choice: either a woman is a dedicated mother and wife, imprisoned in the home, or she is an enlightened, active member of society, liberated from the home.

Islam rejects this “either/or” fallacy.

It presents a “both/and” model, but one that is built on clear and wise priorities.

The Irreplaceable Foundation: The Role of Mother and Wife

The first principle is that the role of a woman within the family—as a wife and, if God wills, as a mother—is foundational, primary, and irreplaceable.

No other person or institution can provide the sakinah, mawaddah, and rahmah that a wife provides.

Even more so, no one can replace a mother in the tarbiyyah (nurturing and upbringing) of a child.

Imam Khamenei states that this is, without exception, a woman’s most important function.

من میگویم مهمترین نقشی که یک زن در هر سطحی از علم و سواد و معلومات و تحقیق و معنویت میتواند ایفا کند، آن نقشی است که بعنوان يك مادر و بعنوان يك همسر میتواند ایفا کند؛ این از همه ی کارهای دیگر او مهمتر است؛ این آن کاری است که غیر از زن کس دیگری نمیتواند آن را انجام دهد.

I say that the most important role that a woman could fulfil—regardless of her level of education, knowledge, research, or spirituality—is that role that she would fulfil as a mother and as a wife. This is more important than all of her other functions; this is something that no one but a woman can fulfil.

— Imam Khamenei, Zan va Khanevadeh (Woman and Family), Page 52

He is clear that a child needs the mother’s embrace, her specific affection, and her gentle guidance to develop a healthy, sound, and un-complexed personality.

This is a divine trust and an unparalleled art.

شما اگر بچه ی خودتان را در خانه تربیت نکردید... اگر تارهای فوق العاده ظريف عواطف او را... با سرانگشتان خودتان باز نکردید تا دچار عقده نشود هیچکس دیگر نمیتواند این کار را بکند؛ نه پدرش و نه به طریق اولی دیگران. فقط کار مادر است... اما آن شغلی که شما بیرون دارید اگر شما نکردید، ده نفر دیگر آنجا ایستاده اند و آن کار را انجام خواهند داد؛ بنابراین اولویت با این کاری است که بدیل ندارد.

If, as a woman, you decide not to raise your children at home... if you decide not to open up the ever-so delicate threads of your child’s emotions... with your own fingertips so that they do not get tangled up later in life, then just know that no one else will be able to do this. Even a father cannot do this, let alone anyone else. This feat can only be accomplished by a mother... As for that employment outside the house, if you cannot do it, there will be tens of people to take your place. Hence, the priority must lie with the task that is irreplaceable.

— Imam Khamenei, Zan va Khanevadeh (Woman and Family), Page 64

The Open Horizon: Permissibility of External Roles

This emphasis on the primary role does not mean the exclusion of women from society.

Islam does not imprison women.

On the contrary, it mandates social responsibility for all believers.

Imam Khamenei strongly refutes the idea that he intends to “imprison” women in the home, using the Quran itself as his primary evidence for their social responsibility:

بعضیها اینطور حرفها را در همان نظر اول با شدت رد میکنند و میگویند آقا شما میخواهید زن را توی خانه اسیر کنید، محبوس کنید، از حضور در صحنه های زندگی و فعالیت باز بدارید؛ نه، به هیچ وجه قصد ما این نیست؛ اسلام هم این را نخواسته. اسلام وقتی که میگوید: «وَ الْمُؤْمِنُونَ وَالْمُؤْمِنَاتُ بَعْضُهُمْ أَوْلِيَاءُ بَعْضٍ يَأْمُرُونَ بِالْمَعْرُوفِ وَيَنْهَوْنَ عَنِ الْمُنْكَرِ»؛ یعنی مؤمنین و مؤمنات در حفظ مجموعه ی نظام اجتماعی و امر به معروف و نهی از منکر همه سهیم و شریکند؛ زن را استثناء نکرده. ما هم نمیتوانیم زن را استثناء کنیم.

“Some people... strongly oppose what we are saying; they would accuse us of wanting to imprison women in their homes and prevent them from participating in social activities. Nothing could be further from the truth; Islam demands nothing of the sort. When God says in the Qur’an:

‘...And the believing men and believing women are allies of one another. They enjoin what is right and forbid what is wrong...

— Quran, Surah al-Tawbah (the Chapter of Repentance) #9, Verse 71’

In other words, believing men and women both play a role in guiding and protecting the community and society as a whole; both must enjoin the good and forbid the evil. Since the Qur’an [in the verse above] has not excluded women, neither must we.”

— Imam Khamenei, Zan va Khanevadeh (Woman and Family), Page 48

Therefore, seeking education, working, and engaging in social or political activity is permissible, and at times, even necessary for women.

ما نمیگوییم زنها کار اجتماعی نکنند... یک کارهای اجتماعی است که واجب است زنها انجام بدهند آن کاری که به عهده ی آنهاست از آنها بر می آید، از غیر آنها بر نمی آید، استعدادش را دارند باید انجام بدهند.

We are not saying women should not do social work... There are some social tasks that are obligatory (wājib) for women to perform; that task which is their responsibility, which they can do, which others cannot do, [and] for which they have the talent, they must perform it.

— Imam Khamenei, Zan va Khanevadeh (Woman and Family), Page 50

The Divine Condition: Balancing the Weave

Here, then, is the crucial point of balance, the condition that ensures the tapestry does not unravel:

The external role must not come at the expense of the primary, irreplaceable internal role.

The family foundation must be protected.

مطلوبیت حضور زن در اجتماع به شرط حفظ بنیان خانواده

The desirability of a woman’s presence in society is conditional upon preserving the foundation of the family.

— Imam Khamenei, Zan va Khanevadeh (Woman and Family), Page 52

This is the divine balance.

A woman can be a student, a doctor, a teacher, or an activist, but these roles must be woven around her foundational role as the heart of the home, not in place of it.

If a career or social activity leads to the neglect of the spouse, the abandonment of tarbiyyah for the children, or the erosion of peace within the home, then a serious imbalance has occurred.

Imam Khamenei cautions that this is a mistake, often driven by Western values that wrongly equate a woman’s worth with her employment status outside the home.

فعالیتهای اجتماعی با حفظ جنبه ی مادری... البته در مواردی شاید کارهای اجتماعی زنان واجب عینی و یا کفایی نیز باشد؛ اما در همه حال خانمها باید فعالیت اجتماعی شان را با حفظ جنبه ی مادری شان بکنند.

Social activities [are permissible] while preserving the aspect of motherhood... Of course, in some cases, a woman’s social work may be an individual obligation (wajib ‘ayni) or a collective obligation (wajib kifa’i); but in all cases, ladies must carry out their social activities while preserving their aspect of motherhood.

— Imam Khamenei, Zan va Khanevadeh (Woman and Family), Page 67

This balance, of course, requires immense wisdom, effort, and crucially, the active support of the husband. A man who understands his wife’s value as a rayhanah and modir will also support her aspirations for growth (education, etc.) that enrich her and the family, provided the core foundation remains secure.

Lessons for the Present: Rejecting the “Either/Or” Fallacy

We must consciously reject the false dichotomy presented by both extremist cultural traditionalism (which seeks to lock women away) and radical secular feminism (which often devalues motherhood as a “burden” or “unfulfilling”).

The Islamic model is one of prioritised balance.

For a woman, this means recognising that her role in building a stable, loving home and raising righteous children is an irreplaceable act of jihad and the most significant contribution she can make to society.

It is her primary domain of wilayah.

For a man, it means fully supporting this role—not by demanding servitude, but by providing protection (qawwam), appreciation, and assistance, enabling her to fulfil this great trust while also facilitating her personal and spiritual growth.

Any external work or study must be weighed against this primary responsibility.

Call to Clarify: Championing the “Both/And” of Islamic Priorities

We must ask ourselves and clarify for our communities:

Are we presenting women with a false choice between family and personal growth?

Let us clarify that Islam champions both, but with clear priorities.

We must clarify that the work of a mother and wife is not a “low-status job” but the most essential, honourable, and irreplaceable vocation for the health of society.

Let us clarify, as Imam Khamenei does, that education, work, and social participation are valuable and permissible for women, on the condition that they do not undermine this foundational role.

We must also clarify for husbands that their duty as qawwam includes supporting their wives’ well-being and growth, not just limiting their activities.

By championing this balanced “both/and” model, we reject extremes and uphold the divine pattern that allows both the family and the individuals within it to flourish.

Weathering the Seasons: Accommodation, Conflict, and Spiritual Support

As the tapestry of marriage unfolds over years and decades, it will inevitably face different “seasons.”

Not all days will be bright; there will be moments of tension, disagreement, and strain.

A tapestry woven only for bright sunlight will fade and tear in the storm.

Islam, therefore, provides us with practical tools for building resilience, managing conflict, and transforming these challenges into opportunities for growth.

The Foundational Principle: Accommodation (Sazegari)

The single most important principle for marital longevity, emphasised repeatedly by our scholars, is sazegari—mutual accommodation and compromise.

This is not a sign of weakness, but of profound strength and wisdom.

Imam Khamenei often recounts a powerful memory of Imam Khomeini (may God rest his pure soul) officiating a marriage:

من یک وقت خدمت امام رفتم، ایشان میخواستند خطبهی عقدی را بخوانند... عقد را اول میخواندند، بعد دو سه جملهی کوتاه صحبت میکردند... رویشان را به دختر و پسر کردند و گفتند: بروید با هم بسازید. ... کلام امام در همین یک جملهی «بروید با هم بسازید» خلاصه میشود.

Once, I went to see Imam Khomeini... he was about to solemnise a couple’s marriage... He turned to the couple and said, “Go and accommodate each other.” ... I thought to myself how we normally give such long talks and yet here the Imam summarised all of it in a single sentence—”Go and accommodate each other.”

— Imam Khamenei, Zan va Khanevadeh (Woman and Family), Page 113

“Go and accommodate each other” is the core directive.

It means actively choosing to build a life together, which requires both partners to move beyond their egos, overlook minor faults, and compromise for the sake of the family unit.

Imam Khamenei describes this accommodation not just as helpful, but as the very basis for the survival of the marriage and an essential necessity:

سازگاری در محیط خانواده جزء واجبات است... سازگاری در زندگی، اساس بقای زندگی است

“Accommodation in the family environment is among the necessities (like wajibat)... Accommodation in life is the basis for the survival of life [i.e., the marriage].”

— Imam Khamenei, Zan va Khanevadeh (Woman and Family), Page 113

This is the practical application of rahmah (mercy).

The Red Line: The Sin of Abuse (Dhulm)

This call for accommodation and patience, however, has a critical red line, just as the duty of concealment (libas) does.

Accommodation does not mean enduring dhulm (oppression).

While disagreements are normal, the method of disagreement is what defines a marriage’s health.

The use of shouting, name-calling, swearing, belittling, threats, or any form of emotional or physical violence is absolutely forbidden (haram) and constitutes dhulm.

This is a gross violation of the covenant.

A spouse who resorts to such behaviour has not only failed to be a libas (garment) but has also violated the command to treat their partner as a rayhanah (cherished flower).

One cannot “accommodate” being crushed.

The Holy Prophet (peace and blessings be upon him and his family) set the standard, stating:

قَالَ رَسُولُ اللَّهِ (ص) خَيْرُكُمْ خَيْرُكُمْ لِأَهْلِهِ وَ أَنَا خَيْرُكُمْ لِأَهْلِي

The Messenger of God (peace and blessings be upon him and his family) said: “The best of you is the best of you to his family, and I am the best of you to my family.”

— Al-Tusi, Al-Amali, Page 390, Hadith 859

This “bestness” is the very antithesis of abuse.

The prohibition against harm is severe.

The Prophet (peace and blessings be upon him and his family) warned in the strongest terms against physical violence in the home:

فَأَيُّ رَجُلٍ لَطَمَ اِمرَأَتَهُ لَطمَةً, أَمَرَ اَللَّهُ عَزَّ وَ جَلَّ مَالِكاً خَازِنَ اَلنِّيرَانِ فَيَلطِمُهُ عَلَى حُرِّ وَجهِهِ سَبعِينَ لَطمَةً فِي نَارِ جَهَنَّمَ

So any man who slaps his wife once, God, Mighty and Majestic, will command Malik, the treasurer of the fires, to slap him on the heat of his face seventy times in the fire of Hell.

— Al-Nuri, Mustadrak al-Wasa’il, Volume 14, Page 250, Hadith 16628

The command from God in the Quran is clear:

...وَعَاشِرُوهُنَّ بِالْمَعْرُوفِ...

...And live with them in kindness (bi’l-ma’ruf)...

— Qur’an, Surah al-Nisa (the Chapter of the Women) #4, Verse 19

Kindness (ma’ruf) is the baseline, and abuse is its direct opposite.

Imam Khamenei is unequivocal on this point, condemning any use of force, coercion, or belittling within the home.

زورگویی مرد در خانه، توهین و تحقیر زن... اینها چیزهایی است که اسلام اجازه نمیدهد.

A man’s use of force in the home, insulting and belittling the wife... these are things that Islam does not permit.

— Paraphrased from Imam Khamenei’s consistent teachings, e.g., in Zan va Khanevadeh (Woman and Family), Page 120-121)

Clarification: The Prohibition of Abuse is Mutual

It is essential to clarify that this ‘Red Line’ of abuse is bidirectional.

While many traditions specifically warn men against harming women—logically, as they hold the position of qawwam and, historically, the greater physical power, making their abuse the more common and structurally dangerous form—the fundamental prohibition against dhulm (oppression) and causing harm (dharar) applies equally to both spouses.

The Quranic metaphor of the garment is perfectly reciprocal:

...هُنَّ لِبَاسٌ لَّكُمْ وَأَنتُمْ لِبَاسٌ لَّهُنَّ...

...They are a garment for you, and you are a garment for them...

— Qur’an, Surah al-Baqarah (the Chapter of the Cow) #2, Verse 187

Just as the husband must protect his wife, she must protect him.

The foundational Prophetic maxim, which is a pillar of Islamic jurisprudence, is universal and applies to all, including spouses:

قَالَ رَسُولُ اللَّهِ (ص): لَا ضَرَرَ وَ لَا ضِرَارَ

The Messenger of God (peace and blessings be upon him and his family) said: “Do not cause harm, and do not reciprocate harm.”

— Al-Kulayni, Al-Kafi, Volume 5, Page 294, Hadith 16

A wife who verbally assaults her husband, belittles his role, engages in constant emotional manipulation (nashizah (rebelliousness) in its broader sense), or psychologically abuses him is also committing dhulm.

This is a reality, particularly in modern contexts where distorted secular ‘isms’ sometimes misinterpret ‘empowerment’ as a license for aggression or disdain, leading to the very real phenomenon of men being abused by their wives.

This is why Imam Khomeini’s advice was “Go and accommodate each other“, not “Go and let the wife accommodate the husband.”

The duty to be a source of sakinah (tranquility) and rahmah (mercy) is mutual.

Oppression has no gender, and the tapestry can be torn by either spouse.

Ayatullah Shaheed Murtadha Mutahhari, in explaining the man’s role, affirms that it is a position of responsibility and service, not a license for despotism.

قرآن که میگوید «اَلرِّجالُ قَوّامونَ عَلَی النِّساءِ» نمیخواهد بگوید مرد یک جنس برتر است و زن یک جنس پستتر... این یک مأموریت و یک تقسیم کار است... این قوام بودن، این ریاست، یک وظیفه است نه یک امتیاز.

When the Quran says, “Men are qawwamun over women,” it does not want to say that man is a superior gender and woman an inferior gender... This is an assignment and a division of labor... This status of being qawwam, this headship, is a duty (wazifah), not a privilege (imtiyaz).

— Ayatullah Murtadha Mutahhari, Majmu’e-ye Asar (Collected Works), Volume 19, The Rights of Women in Islam

Therefore, a husband who uses his position to abuse his wife is not only committing dhulm but is also failing in his primary duty.

Shaykh Alireza Panahian often emphasizes that seemingly small acts of dhulm in the home are grave sins precisely because they violate the home’s sacred purpose as a place of peace.

«در خانه، بد اخلاقی کردن، مثل ریختن سمّ است... تلخ زبانی، دل شکستن، تحقیر کردن، اینها گناهان بزرگی است که در خانه اتفاق میافتد و ما گاهی آن را کوچک میشماریم. حرمت خانه باید حفظ شود. خانه محل آرامش است، نه محل تنش و آزار روحی.»

“Being ill-tempered in the home is like pouring poison... Harsh words, breaking a heart, belittling (tahqir)—these are grave sins (gonahan-e bozorgi) that happen in the home, and we sometimes consider them small (kuchak mi-shomarim).

The sanctity (hormat) of the home must be preserved.

The home is the place of tranquility (mahall-e aramesh), not the place of tension and spiritual/emotional harm (azar-e ruhi).”

—Attributed to Shaykh Alireza Panahian, reflecting his consistent themes in lectures on family ethics

This is a tear in the tapestry that requires immediate mending and, as we discussed in the first point (above), may require seeking external help.

The Highest Support: Partnership in Faith

Beyond simply avoiding harm, the ultimate purpose of accommodation is to create a home so filled with sakinah that both spouses can focus on their spiritual growth.

The highest and most profound form of spousal support is not worldly, but spiritual: helping each other on the path to God.

This is the true meaning of wilayah in the home—being allies in righteousness.

Imam Khamenei explains that this is the greatest assistance a couple can offer one another:

بالاترین کمکی که زن و شوهر به هم میکنند، این است که همدیگر را در راه خدا حفظ کنند، در راه خدا تقویت کنند، در راه مستقیم الهی نگه دارند.

The greatest support that a husband and wife can offer one another is to help each other stay on the path of God. They must assist each other in preserving their faith and protecting the well-being of one another...

— Imam Khamenei, Zan va Khanevadeh (Woman and Family), Page 102

This means practicing amr bi ma’ruf wa nahy anil munkar (enjoining good and forbidding evil) within the home, but doing so with the utmost wisdom (hikmah) and love.

It is not about policing or nagging.

It is about a wife gently and lovingly encouraging her husband to be more patient or to ensure their income is halal, or a husband kindly supporting his wife in her pursuit of Islamic knowledge or her hijab.

This mutual guidance, when done with mawaddah, is the most profound expression of love.

زن و شوهر، بهترین حافظان یکدیگر در صراط مستقیم

Husband and Wife: The Best Guardians of Each Other on the Straight Path

—Imam Khamenei, Zan va Khanevadeh (Woman and Family), Page 102

In a healthy Islamic marriage, spouses are not competitors.

They are teammates, each responsible for helping the other reach Paradise.

Lessons for the Present: The Tools for Weaving

The practical lesson from Imam Khomeini is that we must enter marriage with the intention to accommodate.

This means managing our own ego (nafs).

When conflict arises, the goal should not be to “win” the argument, but to solve the problem in a way that honours the covenant.

This requires active listening, empathy, and a willingness to apologise when wrong.

We must also internalise the absolute prohibition of emotional and verbal abuse.

Shouting at a spouse or calling them names is not a mere “loss of temper”; it is a sin and an act of dhulm.

It is a behaviour that tears the tapestry and cannot be justified.

The highest application of love is to care for our spouse’s akhirah (hereafter).

This means creating an environment where it is easy to be good.

It means praying together, reminding each other of God gently, and celebrating spiritual achievements, making the home a shared platform for ascending towards Him.

Call to Clarify: Accommodation vs. Abuse

We must ask ourselves and clarify for our communities:

Are we promoting the sazegari (mutual accommodation) that Imam Khomeini advised, or are we fostering stubbornness and ego?

Let us clarify that compromise is a strength, not a weakness, and is essential for a lasting marriage.

Most importantly, we must draw a bright, unambiguous line between “accommodation” and “abuse,” in both directions.

Let us clarify that accommodating faults (like messiness or forgetfulness) is a virtue, but accommodating dhulm (oppression like verbal, emotional, or physical abuse) is forbidden and harmful, regardless of who is the perpetrator.

We must clarify—using the clear words of the Prophet (peace and blessings be upon him and his family), Imam Ali (peace be upon him), and our guiding scholars—that Islamic marriage commands mutual kindness (ihsan and ma’ruf) and forbids mutual harm (dharar).

Finally, let us clarify the highest purpose of marriage: spiritual partnership.

Are we merely roommates sharing bills, or are we actively helping each other get closer to God?

We must clarify that the ultimate sign of mawaddah is when a spouse sincerely cares for the other’s spiritual well-being and actively supports their journey on the Straight Path.

The Fruits of the Tapestry: The Sacred Duty of Tarbiyyah

The tapestry we weave through marriage—bound by threads of mawaddah, patterned by the roles of qawwam and rayhanah, and mended by sazegari (accommodation)—is not merely for our own comfort.

Its ultimate purpose is to create a sanctuary, a sacred space for its most precious fruits: the next generation.

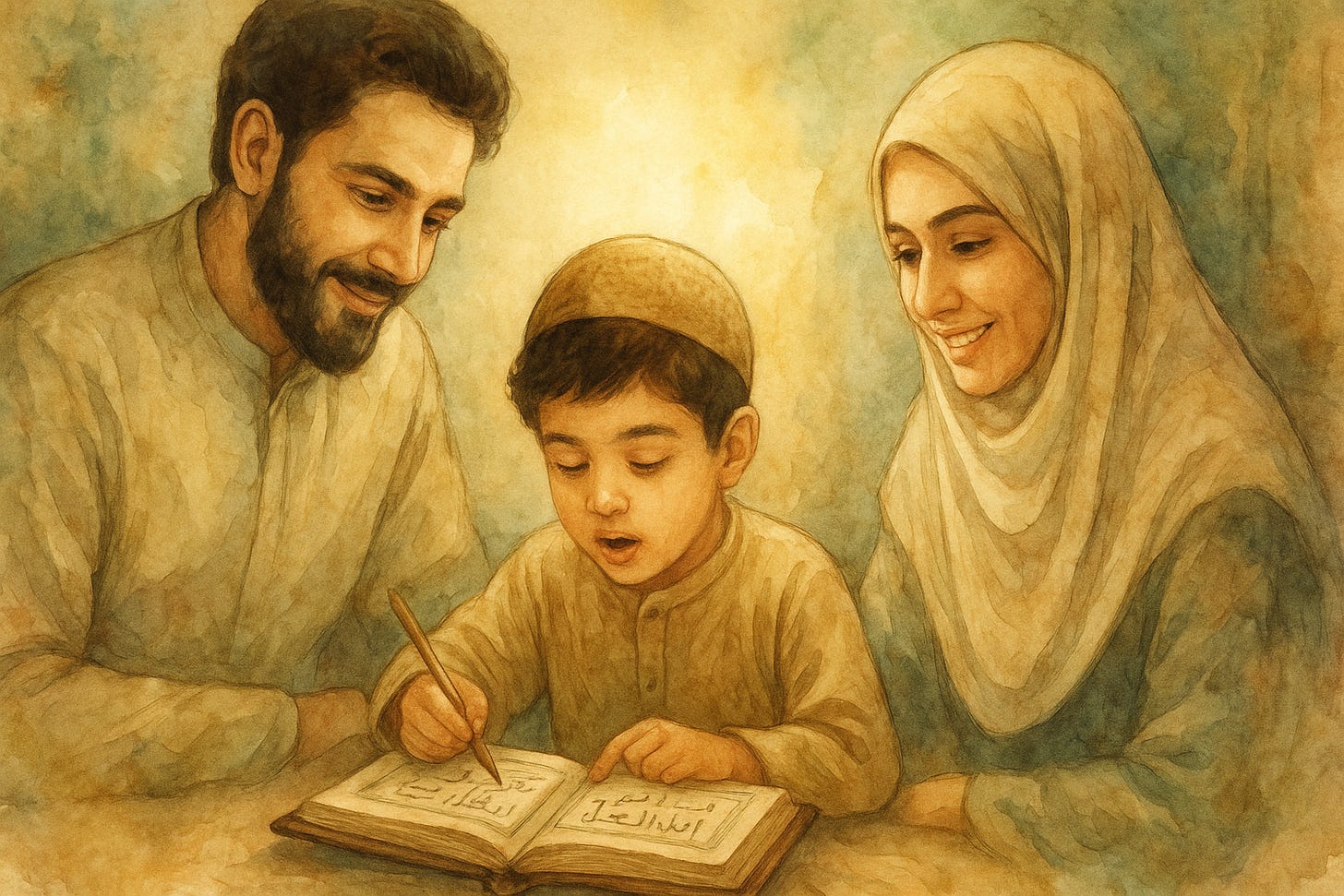

The family, in the Islamic worldview, is the first, most essential, and most powerful school (madrasa) for humanity.

It is here that the foundations of faith, character, and emotional health are laid.

The Irreplaceable Architect: The Mother’s Role

While both parents are responsible for the child’s upbringing (tarbiyyah), Islam designates a central and irreplaceable role for the mother.

This is not a role based on cultural tradition but on divine design, acknowledging the unique spiritual and emotional capacities God has granted her.

No institution, no school, and not even the father, can replicate the formative impact of a mother’s embrace.

Imam Khamenei states this in the clearest possible terms:

شما اگر بچه ی خودتان را در خانه تربیت نکردید... اگر تارهای فوق العاده ظريف عواطف او را... با سرانگشتان خودتان باز نکردید تا دچار عقده نشود هیچکس دیگر نمیتواند این کار را بکند؛ نه پدرش و نه به طریق اولی دیگران. فقط کار مادر است... اما آن شغلی که شما بیرون دارید اگر شما نکردید، ده نفر دیگر آنجا ایستاده اند و آن کار را انجام خواهند داد؛ بنابراین اولویت با این کاری است که بدیل ندارد.

If, as a woman, you decide not to raise your children at home... if you decide not to open up the ever-so delicate threads of your child’s emotions... with your own fingertips so that they do not get tangled up later in life, then just know that no one else will be able to do this.

Even a father cannot do this, let alone anyone else.

This feat can only be accomplished by a mother... As for that employment outside the house, if you cannot do it, there will be tens of people to take your place. Hence, the priority must lie with the task that is irreplaceable.

— Imam Khamenei, Zan va Khanevadeh (Woman and Family), Page 64

This tarbiyyah is not a formal, academic process. It is the transmission of values through presence, affection, and righteous conduct.

مادر میتواند فرزندان را به بهترین وجهی تربیت کند. تربیت فرزند به وسیله ی مادر مثل تربیت در کلاس درس نیست؛ با رفتار است، با گفتار است، با عاطفه است، با نوازش است، با لالایی خواندن است؛ با زندگی کردن است. مادران با زندگی کردن فرزند تربیت میکنند.

A mother can bring up her children in the best way possible. The way she trains her child is very different from what happens in a classroom; it is through her conduct, her conversations, her love, her cajoling, and even her lullabies—in short, it is through how she lives—that her child is trained. Mothers raise children by living.

— Imam Khamenei, Zan va Khanevadeh (Woman and Family), Page 65

This role is a profound jihad and an act of the highest honour.

It is the very art of nurturing a human soul to be healthy, faithful, and “without complexes”.

The Guardian of the Garden: The Father’s Role

The father’s role in tarbiyyah is complementary but equally essential. As the qawwam (protector) of the family, he is responsible for guarding this “nursery.”

He provides the physical security, the halal provision, and the strong framework of wilayah (authority) that allows the mother and children to flourish in peace.

He is the first example of just leadership and strength.

However, his role is not limited to provision. He must also be an active participant in nurturing his children’s faith and character, not as a distant authority figure, but as a compassionate guide and friend.

Imam Khamenei’s advice points to this dual role of authority and intimacy:

The best fathers are those who are friends with their sons and daughters. On the one hand, they offer their fatherly authority and guidance and a helping and loving hand, but on the other, they also offer the intimacy of a friend, if your child has a question, or wants to talk, or needs to confide in someone, let it be to you or your wife that he first turns to.

— Imam Khamenei, The Compassionate Family, Page 131

This theme of the father as both guide (irshad) and friend (rafiq) is a consistent part of his guidance on family life.

Scholarly analyses of his views confirm this emphasis.

The conference paper Islamic Family from the perspective of Ayatollah Khamenei highlights this specific point:

مرد همچنین باید در کنار ارشاد فرزندان با آنها صمیمی و رفیق باشد.

The man must also, alongside guiding (irshad) the children, be intimate (samimi) and a friend (rafiq) with them.

— Sabbaghi Bidgoli, Khaanevadeh-ye Eslami az Didgah-e Ayatullah Khamenei Islamic Family from the perspective of Ayatullah Khamenei), Page 10

Similarly, the academic analysis by Ahmadi & Nodehi identifies several key components of his recommended child-rearing practices (bayesteha-ye tarbiyati), including:

ـ لزوم محبت به فرزندان ـ توجه عمیق به درد دلها و سوالات فرزندان ـ لزوم رفاقت با فرزندان

- The necessity of love for children - Deep attention to children’s heartaches (complaint/confiding) and questions - The necessity of friendship (rifaqat) with children

— Ahmadi & Nodehi, Content Analysing of Ayatullah Khamenei’s viewpoint, Page 24

This confirms that the father’s role is not one of a distant provider, but an active, loving, and friendly guide who listens to his children’s problems and provides a safe space for them to confide.

The Ultimate Goal: Raising Servants of God

The ultimate goal of tarbiyyah in the Islamic paradigm is not to raise children who are merely successful in worldly terms—rich, famous, or professionally accomplished.

The goal is to raise children who are righteous servants of God (‘ibad al-rahman).

The model for this is none other than the family of Sayyedah Fatimah (peace be upon her).

She, the perfect Rayhanah, in a home protected by the perfect Qawwam, raised children—Imam Hassan, Imam Husayn, and Sayyedah Zaynab (peace be upon them all)—whose servitude to God preserved Islam itself.

نقش مادران در پرورش یاران حسین (ع) و زینب (س)

The role of mothers in nurturing the companions of [Imam] Husayn and [Sayyedah] Zaynab

— Imam Khamenei, Zan va Khanevadeh (Woman and Family), Page 67 - Section Heading

This is the standard we aspire to: raising children who recognise the Wilayah of God and His representatives, and who are willing to stand for justice and truth, just as the children of Sayyedah Fatimah (peace be upon her) did.

A Clarification: When the Tapestry Has a Different Pattern (The Test of Infertility)

We must pause here with humility and deep compassion.

For many righteous, loving couples, this discussion of tarbiyyah and children can be a source of profound, silent pain.

They yearn for these fruits, yet for reasons known only to God—perhaps a medical condition, a necessary hysterectomy, or other challenges—they are not granted them.

It is a grave mistake and a form of jahili (ignorant) thinking to interpret this as a divine punishment or a sign of being “damned.”

Infertility is not a failure; it is a profound divine test (ibtilaa’), just as having children is, in itself, a different and heavy test.

We see in the Holy Quran that one of God’s own chosen Prophets, Zakariyya (peace be upon him), experienced this very test, living with the pain of childlessness into his old age.

His story validates the human feeling of sadness, but more importantly, it teaches us the correct response: turning that pain into sincere dua’ (supplication).

وَزَكَرِيَّا إِذْ نَادَىٰ رَبَّهُ رَبِّ لَا تَذَرْنِي فَرْدًا وَأَنتَ خَيْرُ الْوَارِثِينَ

And Zakariyya, when he cried out to his Lord, “My Lord! Do not leave me barren [lit. solitary], and You are the best of inheritors.”

— Qur’an, Surah al-Anbiya (the Chapter of the Prophets) #21, Verse 89

God explicitly states in the Quran that this is part of His sovereign decree and wisdom, not a punishment.

He chooses the nature of our families:

لِّلَّهِ مُلْكُ السَّمَاوَاتِ وَالْأَرْضِ يَخْلُقُ مَا يَشَاءُ يَهَبُ لِمَن يَشَاءُ إِنَاثًا وَيَهَبُ لِمَن يَشَاءُ الذُّكُورَ

أَوْ يُزَوِّجُهُمْ ذُكْرَانًا وَإِنَاثًا وَيَجْعَلُ مَن يَشَاءُ عَقِيمًا إِنَّهُ عَلِيمٌ قَدِيرٌTo God belongs the kingdom of the heavens and the earth. He creates what He wills. He gives female [offspring] to whom He wills, and gives male [offspring] to whom He wills.

Or He couples them, males and females, and He makes barren (‘aqim) whom He wills. Indeed, He is All-Knowing, All-Powerful.— Qur’an, Surah al-Shura (the Chapter of the Consultation) #42, Verses 49-50

To be made ‘aqim is a willed act of the All-Knowing, All-Powerful, no different than being granted a son or a daughter.

The path of patience (sabr) and contentment (rida) for a couple in this situation is an act of ‘ubudiyyah (servitude) of the highest order, weaving threads of profound spiritual strength into their tapestry.

What of the Mawaddah and Rahmah?

For a couple facing this test, the mawaddah and rahmah between them are not diminished; they are magnified.

Their bond becomes their primary sanctuary.

A husband who stands by his wife, offers her solace, and protects her from the ignorant whispers of the community is embodying his role as qawwam in the most noble way.

A wife who remains a source of sakinah for her husband, sharing their grief but building their sabr together, is the epitome of a rayhanah.

Their love is no longer just for building a family, but for surviving a shared test—a profound jihad of the soul.

Redefining “Fruitfulness”: A Broader Tarbiyyah

While submission is key, Islam encourages seeking permissible means. Medical treatments (like IVF, using the couple’s own materials) and surrogacy (Istijar Rahim—permissible with specific, complex conditions under the rulings of scholars like Imam Khamenei and Ayatullah Sistani) are valid avenues to explore.

But if these paths are closed, the tapestry is not incomplete.

God may be freeing the couple for a different, perhaps even broader, mission.

As Shaykh Alireza Panahian often emphasises, the goal of life is not worldly pleasure or even biological continuity, but closeness (qurb) to God, and a test is God’s primary tool for fostering this growth.

«اساساً بنای این عالم بر رنج است... خدا انسان را با رنج آفریده تا او را رشد دهد. لذتها، ابزارهای کمکی هستند برای تحمّل رنجها و برای رسیدن به آن هدف اصلی.»

“Fundamentally, the basis of this world is hardship... God created man with hardship to make him grow. Pleasures are auxiliary tools for bearing the hardships and for reaching that primary goal.”

— Attributed to Shaykh Alireza Panahian, reflecting his consistent themes in lectures on “The Path to Closeness with God”

The sacred duty of tarbiyyah (nurturing) is not, in fact, limited only to one’s own biological children; it is a universal, societal obligation placed on all believers.

The Holy Quran defines the believing community as one of mutual wilayah (guardianship):

...وَالْمُؤْمِنُونَ وَالْمُؤْمِنَاتُ بَعْضُهُمْ أَوْلِيَاءُ بَعْضٍ يَأْمُرُونَ بِالْمَعْرُوفِ وَيَنْهَوْنَ عَنِ الْمُنكَرِ...

...And the believing men and believing women are allies (awliya’) of one another. They enjoin what is right (amr bi ma’rūf) and forbid what is wrong (nahy ‘anil munkar)...

— Qur’an, Surah al-Tawbah (the Chapter of the Repentance) #9, Verse 71

What is tarbiyyah if not the highest form of enjoining good and forbidding evil?

We are all commanded to be shepherds.

The Holy Prophet (peace and blessings be upon him and his family) said:

أَلَا كُلُّكُمْ رَاعٍ وَكُلُّكُمْ مَسْئُولٌ عَنْ رَعِيَّتِهِ

Behold! Each of you is a shepherd, and each of you is responsible for his flock.

— Al-Harrani, Tuhaf al-’Uqul, Page 34

A couple whom God has tested with infertility has not been exempted from this duty; they have merely been guided to practice it on a wider scale.

They are freed to become spiritual parents for the community—to nurture the faith of other young people, to mentor, to teach, and to support the children of the ummah.

Their love and compassion, forged in the fire of their own test, can become a profound source of rahmah for countless others.

Finally, Islam provides the beautiful path of guardianship (kafalah), often referred to as “adoption.”

It is crucial to understand its Islamic framework. Islam forbids the pre-Islamic practice of tabanni, where an adopted child is legally declared one’s own son, taking the family name and inheriting automatically.

مَّا جَعَلَ اللَّهُ لِرَجُلٍ مِّن قَلْبَيْنِ فِي جَوْفِهِ ۚ وَمَا جَعَلَ أَزْوَاجَكُمُ اللَّائِي تُظَاهِرُونَ مِنْهُنَّ أُمَّهَاتِكُمْ ۚ وَمَا جَعَلَ أَدْعِيَاءَكُمْ أَبْنَاءَكُمْ ۚ ذَٰلِكُمْ قَوْلُكُم بِأَفْوَاهِكُمْ ۖ وَاللَّهُ يَقُولُ الْحَقَّ وَهُوَ يَهْدِي السَّبِيلَ

ادْعُوهُمْ لِآبَائِهِمْ هُوَ أَقْسَطُ عِندَ اللَّهِ ۚ فَإِن لَّمْ تَعْلَمُوا آبَاءَهُمْ فَإِخْوَانُكُمْ فِي الدِّينِ وَمَوَالِيكُمْ ۚ وَلَيْسَ عَلَيْكُمْ جُنَاحٌ فِيمَا أَخْطَأْتُم بِهِ وَلَٰكِن مَّا تَعَمَّدَتْ قُلُوبُكُمْ ۚ وَكَانَ اللَّهُ غَفُورًا رَّحِيمًاGod did not place two hearts inside any man’s body. Nor did He make your wives whom you equate with your mothers, your actual mothers. Nor did He make your adopted sons, your actual sons. These are your words coming out of your mouths. God speaks the truth, and guides to the path.

Call them after their fathers; that is more equitable with God. But if you do not know their fathers, then your brethren in faith and your friends. There is no blame on you if you err therein, barring what your hearts premeditates. God is Forgiving and Merciful.— Qur’an, Surah al-Ahzab (the Chapter of the Confederates) #33, Verses 4-5

Instead, Islam extraordinarily praises kafalah (sponsorship/guardianship):

قَالَ رَسُولُ اللَّهِ (ص) أَنَا وَ كَافِلُ الْيَتِيمِ كَهَاتَيْنِ فِي الْجَنَّةِ إِذَا اتَّقَى اللَّهَ عَزَّ وَ جَلَّ وَ أَشَارَ بِالسَّبَّابَةِ وَ الْوُطَى.

The Messenger of God (peace and blessings be upon him and his family) said: “I and the guardian (kafil) of an orphan will be like these two in Paradise, if he is pious (ittaqa) towards God, Mighty and Majestic,” and he gestured with his index and middle fingers.

— Shaykh Saduq, Man La Yahduruhu al-Faqih, Vol. 2, p. 67, Hadith 1731

This is a path to direct companionship with the Prophet (peace and blessings be upon him and his family).

While bringing a child into the home is one form of kafalah, it has significant fiqhi complexities (like mahramiyyat) that require direct consultation with a scholar.

However, it is crucial to clarify that kafalah is not limited to bringing a child into one’s home.

A powerful, accessible, and widely practiced form of tarbiyyah is the remote sponsorship of an orphan or child in need, whether in one’s own locality or abroad.

In this beautiful model, a couple provides the financial support for a child’s education, healthcare, and general well-being. This fulfils the sacred duty of kafalah in a profound way and circumvents the complex challenges of mahramiyyat.

This path provides an immense spiritual and emotional release, allowing a couple to channel their mawaddah and rahmah into the tarbiyyah of a child.

They can often build a meaningful, personal relationship with the child through letters, video calls, or organised visits, becoming a direct and lasting source of mercy and guidance in that child’s life.

This is not “washing one’s dirty linen”; this is actively “washing” the world’s sorrows with one’s blessings, turning a personal test into a source of universal good.

Many noble organisations facilitate this work, such as the renowned Al-Mabarrat Association in Lebanon (founded by the late Ayatullah Sayyed Muhammad Hussein Fadhlullah) and countless other orphan foundations worldwide, which connect sponsors with children in need.

A couple tested with infertility is not “damned” or “incomplete”, nor are they deemed any lesser in the eyes of God.

Their path may be one of profound sabr, medical recourse, or of opening their hearts to the children of the ummah through this very kafalah.

Their “fruit” becomes the sabr itself, or the tarbiyyah of an entire community, or the selfless love given to a child who is not of their blood but is of their heart.

A Note on a Difficult Path: The Option of Polygyny

In this discussion of childlessness as a profound test, we must address one of the most delicate and often misunderstood paths: the fiqhi (juridical) permissibility for a husband to take a second wife.

We must be clear: this path is permissible (halal).

The Holy Quran states:

...فَانكِحُوا مَا طَابَ لَكُم مِّنَ النِّسَاءِ مَثْنَىٰ وَثُلَاثَ وَرُبَاعَ فَإِنْ خِفْتُمْ أَلَّا تَعْدِلُوا فَوَاحِدَةً...

...then marry those that please you of [other] women, two or three or four. But if you fear you will not be just (ta’dilu), then [marry] only one...

— Qur’an, Surah al-Nisa (the Chapter of the Women) #4, Verse 3

This verse provides the legal basis.

However, in our school of Wilayah, we do not just read the law; we must understand the wisdom (hikmah) and the spirit.

The permissibility is immediately and inextricably bound to a severe condition: Justice (‘adalah).

This condition of justice is not optional. It is the pillar upon which the permissibility rests.

Ayatullah Sistani, in his Minhaj al-Salihin, clarifies this legal obligation:

المسألة 1051: يجوز للرجل أن يتزوّج أربع زوجات دائمات ... والمشهور أنّ شرط جواز التعدّد هو الوثوق بالقدرة على العدل بينهنّ في الإنفاق والمبيت.

Issue 1051: It is permissible for a man to marry up to four permanent wives... and the well-known (mashhur) [ruling] is that the condition for the permissibility of polygyny is having confidence (al-withuq) in one’s ability to practice justice (’adl) between them in maintenance (al-infaq) and in spending the night (al-mabit).

— Ayatullah Sistani, Minhaj al-Salihin, Vol. 3, Marriage Section, Issue 1051

Thus, if a man cannot guarantee this equal provision of time and resources, the fiqhi path itself becomes problematic for him. But the Quran goes even deeper, pointing out the near impossibility of true justice, which includes the heart:

وَلَن تَسْتَطِيعُوا أَن تَعْدِلُوا بَيْنَ النِّسَاءِ وَلَوْ حَرَصْتُمْ فَلَا تَمِيلُوا كُلَّ الْمَيْلِ...

You will never be able to be [perfectly, emotionally] just between wives, even if you are eager. So do not incline completely [toward one]...

— Qur’an, Surah al-Nisa (the Chapter of the Women) #4, Verse 129

This verse serves as a profound divine warning.

While perfect emotional justice is not a condition (as it’s impossible), a man who knows he will “incline completely” (tamilu kull al-mayl) away from his first wife, depriving her of her rights to companionship and kindness, is here being directly warned against this path.

The Hikmah (Wisdom) of the Ruling

Ayatullah Shaheed Murtadha Mutahhari (may God rest his pure soul) explains that Islam did not initiate polygyny; it regulated and limited a pre-existing, unrestricted practice.

He argues its permissibility was retained primarily as a social solution to social crises—such as a surplus of war widows and orphans—not as a license for personal indulgence.