[28] Imamah (Leadership) - Sayyedah Zaynab, Imam Sajjad and the Messengers of Karbala

A series of discussions on the teachings of Imam Sadiq (sixth Imam of the Muslims), from the book Misbah ash-Sharia (The Lantern of the Path)

In His Name, the Most High

This is part twenty-eight of an ongoing series of discussions on the book attributed to Imam as-Sadiq entitled ‘Misbah ash-Sharia’ (the Lantern of the Path).

As is the case for each of the sessions in this series (and previous series), there is a requirement for the reader to at the very least take a cursory look at the previous sessions - though studying them properly is more beneficial - as the nature of this subject matter requires, a building up of understanding in a step by step manner.

Since each session builds on the one before, it is crucial that the previous sessions are studied - at least in a cursory manner, though fully is more beneficial - so we can try to ensure that misunderstandings and confusion do not ensue, as well as ensure we can garner more understanding from each session.

The previous parts can be found here:

Video of the Majlis (Sermon/Lecture)

This is the video presentation of this write-up as a Majlis (part of the Truth Promoters Weekly Wednesday Majlis Program)

Audio of the Majlis (Sermon/Lecture)

This is the audio presentation of this write-up as a Majlis (part of the Truth Promoters Weekly Wednesday Majlis Program)

Recap

In the previous session, we walked with reverence and resolve into the uprising of Imam Husayn ibn Ali, peace be upon him — not as a mere tale of martyrdom, but as the fulfilment of a divine obligation long deferred.

We examined how, by the time of Yazid’s accession, Islam stood on the precipice of annihilation — its form preserved, but its spirit hollowed out. The Umayyad regime had not only corrupted governance but had begun to mask tyranny in the garments of religion. Wealth replaced worship. Power replaced piety. And the Quran was recited by tongues that mocked its commands.

It was in this moment of existential peril that Imam Husayn rose — not for power, not to embrace death, but to revive the obligation of enjoining good and forbidding evil. This was no reactionary protest, nor a political gamble. It was the calculated fulfilment of a duty that neither the Prophet, nor Imam Ali, nor Imam Hasan had enacted — because the historical conditions had not yet ripened.

We explored:

The gradual internal corruption that began among the early elite

The transformation of the caliphate into monarchy under Muawiyyah and Yazid

The abandonment of Quranic justice in favour of tribal privilege and dynastic rule

The moral and theological collapse that demanded a stand — even if that stand ended in blood

We listened to Imam Husayn’s own words — in Madinah, in Makkah, in Bayda, in Karbala — as he clarified again and again the nature of his mission: not to rule, not to die, but to reform. To awaken. To restore.

His uprising drew its legitimacy from the Quran, from the Sunnah of the Prophet, and from the path of his father Ali ibn Abi Talib. It was not an act of emotion — it was an act of fiqh. A jurisprudential, spiritual, and historical necessity.

And though the swords of Karbala fell, the mission did not end. If Husayn was the voice, then the echo still remained.

As this next session begins, we follow the aftermath of Ashura — the bearers of the message — those who survived to carry the truth into the courts of falsehood, who turned shackles into sermons, and captivity into clarity.

We continue — in the name of the Lord of the Martyrs and the Truthful …

Imamah (Leadership) - Sayyedah Zaynab, Imam Sajjad and the Messengers of Karbala

The True Greatness of Sayyedah Zaynab

The Greatness Not Inherited, But Realised

Sayyedah Zaynab al-Kubra — the radiant daughter of Imam Ali ibn Abi Talib (peace be upon him) and Sayyedah Fatimah az-Zahra (peace be upon her) — is revered not simply for her noble lineage, but for the divine stand she took in the darkest of times. Her greatness was not a passive inheritance; it was a conscious, courageous choice. Though she was born into the house of revelation and nurtured in the cradle of wilayah, her loftiness was earned through sacrifice, insight, and unwavering loyalty.

Indeed, not every daughter of an Imam becomes Zaynab. The Quran declares:

إِنَّ أَكْرَمَكُمْ عِندَ ٱللَّهِ أَتْقَىٰكُمْ

“Indeed, the most honourable of you in the sight of God is the most Godwary among you.”

— Quran, Surah al-Hujurat (the Chapter of the Chambers) #49, Verse #13

It was her taqwa (God wariness), her sabr (fortitude), her fahm (understanding), and her qiyam (stand) that elevated her to the rank of the awliya (friends, representatives of God).

She was not defined merely as the sister of Imam Hasan and Imam Husayn (peace be upon them), but as the bearer of a message when all voices were silenced, the veiled warrior who rose where even many men faltered.

In the tradition of the righteous, God describes those who “sell themselves seeking the pleasure of God”:

وَمِنَ ٱلنَّاسِ مَن يَشْرِي نَفْسَهُ ٱبْتِغَآءَ مَرْضَاتِ ٱللَّهِ ۗ وَٱللَّهُ رَءُوفٌۢ بِٱلْعِبَادِ

“Among the people is he who sells his soul seeking the pleasure of God, and God is most kind to His servants.”

— Quran, Surah al-Baqarah (the Chapter of the Cow) #2, Verse #207

Sayyedah Zaynab sold herself for the sake of God’s cause, giving up her comfort, her children, her name, her body, her rest — to carry the blood of truth through the streets of Kufa and the palaces of Damascus. She knew what awaited the caravan, yet she joined — not as a passive companion, but as a central pillar of the movement of Ashura.

The Prerequisite of Greatness: Understanding the Moment

What marks her out from the elite companions of that age — from men like Ibn Abbas and Ibn Ja‘far — is not mere boldness, but discernment. Many among the Quraysh nobility and even the Ahl al-Bayt hesitated. They saw the peril, the overwhelming odds, the certainty of massacre — and they paused. Zaynab did not. She recognised the wajib al-waqt — the obligation of the moment. It was not just about following her brother. It was about answering the divine call of wilayah with yaqeen (conviction).

She walked not blindly, but with full knowledge. As the Quran says:

يُؤْتِى ٱلْحِكْمَةَ مَن يَشَآءُ ۚ وَمَن يُؤْتَ ٱلْحِكْمَةَ فَقَدْ أُوتِىَ خَيْرًۭا كَثِيرًۭا

“He grants wisdom to whomever He wishes, and he who is granted wisdom has certainly been given much good.”

— Quran, Surah al-Baqarah (the Chapter of the Cow) #2, Verse #269

Sayyedah Zaynab possessed that hikmah — divine insight into when to speak and when to remain silent, when to mourn and when to mobilise.

The Greatness of Choice, Not Lineage

Her greatness was therefore not pre-scripted. It was forged moment by moment: from the day she resolved to accompany Imam Husayn, to the night she buried her sons Awn and Muhammad, to the hours she stood before Ibn Ziyad and Yazid without flinching.

The Imams themselves recognise that true nobility lies in one’s stand. Imam Ali is reported to have said:

قِيمَةُ كُلِّ امْرِئٍ مَا يُحْسِنُهُ

“The worth of every person is in what they excel at.”

— Nahjul Balagha1, Hikmah (Saying) #81

And what did Sayyedah Zaynab excel in? In her knowledge, in her loyalty, in her sorrow — and most of all, in her ability to carry the light of Imamah through the darkest of nights.

The Decision to Join the Caravan of Ashura

The Path of Certainty in a Time of Confusion

Before the caravan departed for Karbala, the landscape was clouded by hesitation and fear. Among those surrounding Imam Husayn (peace be upon him) were many esteemed figures: Ibn Abbas, Ibn Ja‘far, and other veterans of early Islam — men of knowledge and lineage, known for their counsel and social standing.

Yet in that hour, many faltered. They saw the political deadlock, the threat of annihilation, and the hopelessness of a stand against the tyranny of Yazid.

But Sayyedah Zaynab (peace be upon her) did not flinch.

She did not stand still, nor did she offer reluctant support. She moved — consciously, sacrificially, and with spiritual clarity. She knew that this journey was not about survival; it was about witness.

Her decision was not rooted in ignorance of the dangers ahead. Quite the opposite — her heart felt the approaching catastrophe more deeply than anyone. But conviction, not comfort, was her guide.

Imam Ali once said:

ثَبَتَ الْقَائِلُ عَلَى بَصِيرَةٍ يَهْتَدِي بِهَا، وَدَاعٍ إِلَى الْحَقِّ، فَصَعِقَ فِي سَبِيلِهِ

“He stood firm with clear insight, guided by it, and calling others to truth — until he was struck down in the path of God.”

— Nahjul Balagha2, Sermon #182

Sayyedah Zaynab too stood with basira — insight. She followed not simply as a sister, but as a mujahedah — a fighter for divine truth, a supporter of the Imam whose stand would preserve the path of prophethood.

The Departure: A Woman on a Divine Mission

Sayyedah Zaynab left her home and her husband, Abdullah ibn Ja‘far. Some accounts suggest he initially opposed her decision to bring their sons — Awn and Muhammad — to the battlefront. But Sayyedah Zaynab insisted. She did not merely accompany Imam Husayn; she armed him with her own children.

Just as Sayyedah Fatimah as-Zahra defended the wilayah of Amir al-Mu’mineen after the Prophet’s demise, Sayyedah Zaynab rose to defend the wilayah of her brother — with her life, her voice, and her lineage.

One report from the maqtal narrations indicates her unwavering spirit:

وَاللَّهِ لَا أَفَارِقُ أَخِي وَلَوْ قُطِّعْتُ بِالسُّيُوفِ

“By God, I will never abandon my brother, even if I am cut to pieces by swords!”

This was not familial loyalty. It was theological commitment. As Sayyedah Zaynab saw it, the stand of Karbala was not merely a political rebellion — it was the safeguarding of the entire message of Prophet Muhammad, the entire message of Islam, it was a trust (amanah).

Bearing the Weight Others Could Not

At that same time, men of nobility hesitated. Swords were sheathed. Minds were confused. But Sayyedah Zaynab did not waver. She understood the prophetic words of her grandfather, the Messenger of God (peace and blessings be upon him and his family):

إِنَّ لِكُلِّ شَيْءٍ دَعَائِمَ، وَدَعَائِمُ هَذَا الدِّينِ حُبُّنَا أَهْلَ الْبَيْتِ

“Every structure has pillars, and the pillars of this religion are love for us, the Ahl al-Bayt.”

— Al-Hindi5, Kanz al-Ummal6, Hadeeth #32970

— Al-Majlisi7, Bihar al-Anwar8, Volume 27, Page 91

Her presence was one of those pillars. She became the breath of the movement, the eloquence of its truth, the shield of its survivors. She bore not only the hardship of the journey, but the agony of anticipation — bringing her sons with her to what she knew was a field of martyrdom.

And when the men around her were paralysed by uncertainty, it was she who steadied their Imam. It was she who comforted Imam Husayn, offered him her loyalty, and prepared him to face the day of Ashura.

Sayyedah Zaynab After the Martyrdom of Imam Husayn

A Light in the Darkness

After the martyrdom of Imam Husayn (peace be upon him), the skies of Karbala darkened — not merely in hue, but in the soul of the world. The Quran speaks of a night “as it spreads its darkness”:

وَٱلَّيْلِ إِذَا يَغْشَىٰ

“By the night as it envelops.”

— Quran, Surah al-Layl (the Chapter of the Night) #92, Verse #1

This darkness was not the natural fall of dusk — it was a spiritual eclipse. The earth had swallowed the blood of the grandson of the Prophet (peace and blessings be upon him and his family).

The last light of hope seemed extinguished.

Yet it was precisely in that moment that another luminary rose — veiled, wounded, grieving — but radiant. Sayyedah Zaynab (peace be upon her) did not allow the tragedy to close the chapter of Karbala.

She opened it.

It was through her that Karbala did not end in death, but began as a revolution. Her presence was not merely complementary to Imam Husayn — it was continuative.

As Ayatullah Murtadha Mutahhari9 said:

اگر خطبههای زینب و امام سجاد نبود، پیام کربلا در کربلا دفن میشد

If it were not for the sermons of Sayyedah Zaynab and Imam Sajjad, the message of Karbala would have been buried in Karbala.

Another Husayn in the Garb of a Woman

The legacy of Sayyedah Zaynab was not that she wept for her brother — though she did — but that she stood in his place when none else could.

Imam Husayn had raised an army; Sayyedah Zaynab would raise a voice. He carried the Quran on the blade of his sword; she carried it on the edge of her tongue.

One eyewitness described her after Ashura:

كَأَنَّهَا الْحُسَيْنُ الثَّانِي فِي ثِيَابِ ٱمْرَأَةٍ، وَبَلَاغَتُهَا تُحْيِي قُلُوبَ الْمَيِّتِينَ

“It was as though she was another Husayn — in the clothing of a woman. Her eloquence revived the hearts of the dead.”

— Al-Majlisi12, Bihar al-Anwar13, Volume 45, Page 114

— Al-Tabarsi14, Mustadrak al-Wasail15, Volume 3, Page 303

This was not metaphor. It was recognition. The divine wisdom that had descended upon the heart of the Prophet flowed also through her tongue. Her silence was ibadah (worship). Her movement was a khutbah (sermon). Her eyes carried the pain of Sayyedah Fatimah az-Zahra and the resolve of Amir al-Mu'mineen.

The Continuity of Wilayah Through a Woman

Sayyedah Zaynab embodied the Quranic model of those who are entrusted with the divine cause:

فَأَثَٰبَهُمُ ٱللَّهُ بِمَا قَالُوا۟ جَنَّٰتٍۢ تَجْرِى مِن تَحْتِهَا ٱلْأَنْهَـٰرُ خَـٰلِدِينَ فِيهَا ۚ وَذَٰلِكَ جَزَٰٓؤُا۟ ٱلْمُحْسِنِينَ

“So God rewarded them for what they said with gardens beneath which rivers flow, to abide therein, and that is the reward of the virtuous.”

— Quran, Surah al-Maidah (the Chapter of the Table Spread) #5, Verse #85

Her words were not reactions; they were revelation-aware responses. She knew that Ashura was not the end, but the middle — the turning point of history’s axis.

Without Sayyedah Zaynab, Karbala would have been a sealed grave. With her, it became an open book — a living scripture of sacrifice and divine resistance.

Emotional Depth and Divine Strength

Strength Clothed in Mercy

Sayyedah Zaynab (peace be upon her) was not an iron figure stripped of emotion. She was a daughter of the Prophet of Mercy — and that mercy flowed through her. But what made her divine stand so extraordinary was not the absence of emotion — it was the disciplining of it.

She expressed concern twice to her brother, Imam Husayn (peace be upon him): once during the journey, after hearing troubling reports, and once again on the eve of Ashura.

In both moments, her emotion was not rooted in fear for herself, but in sorrow for her brother — the Imam of her time, the remnant of her grandfather’s light.

This is a woman who, as the Quran says:

ٱلَّذِينَ إِذَآ أَصَـٰبَتْهُم مُّصِيبَةٌۭ قَالُوٓا۟ إِنَّا لِلَّهِ وَإِنَّآ إِلَيْهِ رَٰجِعُونَ

“Those who, when disaster strikes them, say: ‘Indeed we belong to God, and indeed to Him we return.’”

— Quran, Surah al-Baqarah (the Chapter of the Cow) #2, Verse #156

Her composure did not contradict her emotion. Her grief did not hinder her resolve. She wept, but she marched. She trembled inside, but stood firm outwardly — embodying sabr (fortitude) in its most complete sense.

Her Grief, His Assurance

In one of the caravan’s stopovers, Zaynab approached Imam Husayn and said: “O brother, I feel there is danger. I know this path leads to martyrdom and captivity, but something in my heart is heavy.”

Imam Husayn’s reply was simple and anchored in divine surrender:

مَا شَاءَ ٱللَّهُ كَانَ

“That which God wills — occurs.”

— Al-Kulayni16, Al-Kafi17, Volume 3, Book of Divine Unity, Chapter on God’s Will and Intention, Page 530.

This phrase — echoed later by Sayyedah Zaynab herself in the court of Yazid — reflects the heart of tawheed: a worldview in which even grief submits to divine decree.

This moment was not one of weakness, but of tahawwul — sacred transformation. Her sorrow did not lead to despair. Instead, it purified her heart and prepared her soul. And after that moment, she asked him nothing further.

A Mercy Formed in Fire

Just as the Prophet Muhammad (peace and blessings be upon him and his family) wept at the grave of his son Ibrahim, and as Amir al-Mu’mineen trembled before the body of Sayyedah Fatimah az-Zahra, Sayyedah Zaynab’s emotions were not signs of frailty — they were evidence of her humanity.

The Imams are not stones. They are hearts of divine fire, and their companions — like Sayyedah Zaynab — inherited this balance between mercy and might.

Imam al-Sajjad is reported to have said:

إِنَّ الْحُزْنَ فِي قُلُوبِنَا وَاللَّهِ، لَا يَذْهَبُ أَبَدًا

“Indeed, sorrow remains in our hearts — by God — and it shall never depart.”

— Al-Majlisi18, Bihar al-Anwar19, Volume 44, Page 292

— Ibn Tawus20, Al-Luhuf21, Page 157

— Al-Qummi22, Nafas al-Mahmum23, Page 203

This sorrow is not paralysing. It is mobilising. And Sayyedah Zaynab proved this — again and again.

The Night Before Ashura

The Night of Farewell and Revelation

The night before Ashura descended upon Karbala like a heavy silence before a great storm. In the tents of the Ahl al-Bayt, children tried to sleep. Some sharpened swords. Others whispered words of dhikr. But one tent stood at the centre of it all — the tent of Imam Husayn (peace be upon him), where the shadow of martyrdom had already begun to fall.

Imam Ali ibn Husayn Zayn al-Abedeen (peace be upon him) later narrated what occurred:

قال علي بن الحسين (ع): إني لجالس في تلك العشية في فسطاطي، وعمتي زينب تمرضني، إذ اعتزل أبي في خبائه وأصحابه في أخبيتهم، فغلبته عيناه، ثم استيقظ وهو يقول:

"يا دهر أف لك من خليل ... كم لك بالإشراق والأصيل

من صاحب أو طالب قتيل ... والدهر لا يقنع بالبديل

وكل حي سالك سبيلي"فعلمت أنه قد نعيت إليه نفسه، وأقبلت عمتي زينب تبكي وتقول: وا ثكلاه! ليت الموت أعدمني الحياة اليوم.

“I was sitting that evening in my tent, and my aunt Zaynab was tending to me. My father was alone in his tent, and his companions were in theirs. Sleep overcame him, then he awoke reciting:

“O Time! Fie on you as a friend —

How many dawns and dusks you bring —

Slaying the seeker and the companion alike —

Never content with any replacement.”I knew then that his own death had been foretold to him. My aunt Zaynab came, weeping...”

Sayyedah Zaynab (peace be upon her), hearing this, could no longer contain her sorrow. She stood, crossed to her brother’s tent, and addressed him with trembling words:

يَا أَخِي الْعَزِيزَ! أَتُنَادِي بِالْمَوْتِ؟ حَتَّى الْآنَ كَانَ قَلْبِي ثَابِتًا بِسَبَبِكَ. لَمَّا تُوُفِّيَ أَبُونَا، وَجَدْتُ الْقُوَّةَ فِيكَ. وَلَمَّا اسْتُشْهِدَ الْإِمَامُ الْحَسَنُ (ع)، قُلْتُ: أَخِي الْحُسَيْنُ مَا زَالَ حَيًّا. هَدَّأْتُ رُوحِي بِوُجُودِكَ. وَلَكِنِ الْآنَ...

“O my dear brother! Are you announcing your death? Until now my heart had remained firm because of you. When our father passed, I found strength in you. When Imam Hasan was martyred, I said: my brother Husayn still lives. I calmed my soul with your presence. But now…”

— Attributed to Sayyedah Zaynab26

These were not mere sentiments — they were the tears of a woman who had endured everything, and was now about to face the abyss.

The Heart of the Husayni Movement

Sayyedah Zaynab’s grief in this moment was not hesitation — it was an expression of ma‘rifah (recognition). She recognised the immensity of what was about to unfold. Unlike others, she had no illusions of victory in worldly terms. What pained her was not the loss of battle — but the separation from the Imam, the living proof of God on earth.

The Quran speaks of this spiritual grief in the story of Jacob (Ya’qub):

وَٱبْيَضَّتْ عَيْنَاهُ مِنَ ٱلْحُزْنِ فَهُوَ كَظِيمٌۭ

“And his eyes turned white with grief, and he was choked with sorrow.”

— Quran, Surah Yusuf (the Chapter of (Prophet) Joseph) #12, Verse #84

If Yaqub wept for Yusuf, how much more did Zaynab weep for Husayn?

But even in this moment of collapse, she stood. She spoke with dignity. She wept — and then she prepared herself for the aftermath. For after Husayn would fall, she would rise.

The Ordeal of the Women and Children

The Night of Ashura’s Aftermath

After the sun of Ashura set, a night unlike any other enveloped the plains of Karbala. The tents stood silent, pierced by the weeping of orphans and the wails of widows. There were no more warriors. No more swords clanged. Only stillness, grief, and the scent of death.

Sayyedah Zaynab al-Kubra (peace be upon her) stood in the middle of it all — surrounded by chaos and corpses, flames and fear — and she became the spine of the camp.

There were approximately eighty-four survivors, mostly women and children, huddled together under a sky now emptied of its stars. Among them was only one man, and even he — Imam Zayn al-Abedeen — was gravely ill, barely conscious, unable to walk.

Sayyedah Zaynab bore the burden of leadership — not by declaration, but by necessity. She was the remaining strength of the family of the Prophet. The Quran describes such people with a sacred eloquence:

فَصَبْرٌۭ جَمِيلٌۭ ۖ وَٱللَّهُ ٱلْمُسْتَعَانُ عَلَىٰ مَا تَصِفُونَ

“So patience is beautiful — and God is the One sought for help against what you describe.”

— Quran, Surah Yusuf (the Chapter of (Prophet) Joseph) #12, Verse #18

Between Grief and Guardianship

Sayyedah Zaynab had not merely lost her brother. She had lost her sons, her nephews, her family’s dignity in the eyes of a brutal world. Yet even then, she did not collapse. She moved swiftly — from tent to tent, from mother to orphan, from the dying to the traumatised — gathering the survivors like a shepherd in a storm.

Her courage was not in never breaking down, but in choosing when to allow her grief to speak. And when she spoke, she did not complain. She rose to the body of her brother, broken and bloodied, and called out:

يَا مُحَمَّدَاه! هَذَا حُسَيْنٌ بِالْعَرَاءِ، مَسْلُوبُ الْعِمَامَةِ وَالرِّدَاءِ! مَقْطُوعُ الْأَعْضَاءِ!

“O my grandfather Muhammad! This is your Husayn — exposed on the ground, stripped of his cloak and turban, his limbs severed!”

The angels, it is said, wept from the heavens. But Sayyedah Zaynab did not only weep. She took command of the shattered camp. She became the leader (qibla) of the orphaned, the shelter of the survivors.

A Woman Made of Iron and Light

Sayyedah Zaynab proved in that night what the Imams had always taught: that wilayah is not limited to gender or age. It is about who stands when others fall. It is about who protects the divine trust when no protectors remain.

Imam Ali once said:

إِنَّ الْحَقَّ ثَقِيلٌ، وَلَا يَحْمِلُهُ إِلَّا أُولُو الْبَصَائِرِ وَالصَّبْرِ

The truth is heavy, but none shall carry it except those with insight and endurance.

— Nahjul Balagha29, Paraphrased from Sermons #88, #189, and #192

Sayyedah Zaynab was not exploited by the crisis — she mastered it. She used no sword, yet she defended the message. She gave no khutbah yet — yet — but her actions spoke louder than blood.

Her Final Refuge: The Slain Body of Her Brother

In the deep night of sorrow, when the flames had devoured the tents and the cries of children echoed unanswered, Sayyedah Zaynab (peace be upon her) found herself drawn to the resting place of her brother. It was not rest she sought — but refuge. He was her pillar, her Imam, her strength. Now he lay butchered, lifeless, headless, alone.

She approached his mutilated body, scattered in parts upon the ground, and stood above it — not as a sister mourning a brother, but as a woman mourning the last remnant of Prophethood upon the earth.

Then, from the depths of her being, she cried:

يَا مُحَمَّدَاه! صَلَّى عَلَيْكَ مَلَائِكَةُ السَّمَاءِ! هَذَا حُسَيْنٌ مُرَمَّلٌ بِالدِّمَاءِ! مَقَطَّعُ الْأَعْضَاءِ!

“O Muhammad! May the angels of the heavens send blessings upon you! This is your Husayn, drenched in blood, his limbs severed!”

This cry was more than grief — it was a proclamation. She was addressing the heavens and the earth, the angels and the tyrants, the past and the future.

The Triumph of the Slain

In this very moment, the philosophy of Karbala reached its zenith. The Imam was silent in death — but the blood cried out through Sayyedah Zaynab. Her shout was not despair. It was declaration. It marked the moment when the sword of tyranny lost to the blood of sacrifice.

Imam al-Baqir later said:

إِنَّ اللَّهَ تَبَارَكَ وَتَعَالَى بَارَكَ فِي الْقَتْلِ لَنَا كَمَا بَارَكَ فِي الرِّسَالَةِ لِنَبِيِّنَا

“Surely God, Blessed and Exalted, has sanctified our martyrdom just as He sanctified Prophethood for our Prophet.”

— Al-Kulayni, Al-Kafi, Volume 1, Book of Proof, Page 446, Hadeeth #9

Sayyedah Zaynab understood this. She knew that Imam Husayn’s blood had not ended his movement — it had begun it.

Blood Over Sword

The Quran reminds us that:

وَلَا تَحْسَبَنَّ ٱلَّذِينَ قُتِلُوا۟ فِى سَبِيلِ ٱللَّهِ أَمْوَٰتًۭا ۚ بَلْ أَحْيَآءٌ عِندَ رَبِّهِمْ يُرْزَقُونَ

“Do not suppose those who were slain in the way of God to be dead. No, they are alive, being provided for by their Lord.”

— Quran, Surah Aal-e-Imraan (the Family of Imraan) #3, Verse #169

Sayyedah Zaynab was the first to testify to this truth after Karbala. Her lament at the body of her brother was not defeat — it was declaration of victory.

The blood had conquered the sword. And the world, ever since, has repeated her message.

From Military Defeat to Moral Victory

From Ashes to Ascent: The Alchemy of Sayyedah Zaynab’s Stand

Had Karbala ended with swords and severed heads, it would have been remembered as a tragic footnote in the annals of power.

But it did not end.

It began.

It transcended battlefield and bloodshed — because one woman refused to let truth be buried with the bodies.

Sayyedah Zaynab al-Kubra (peace be upon her) transformed what appeared to be a military defeat into a moral and spiritual victory without equal.

In the material world, Imam Husayn was killed. His companions massacred. His body mutilated. His family taken captive. But in the language of the unseen (ghayb), it was Yazid who was exposed, stripped of legitimacy, and eternally humiliated.

As Imam Ja‘far al-Sadiq declared:

إِنَّ اللَّهَ عَزَّ وَجَلَّ أَعَطَى الْحُسَيْنَ أَجْرَ مَنْ قُتِلَ مَعَهُ، وَمِنْ بَقِيَ مِنْ ذُرِّيَّتِهِ

“Surely God, Mighty and Majestic, granted Husayn the reward of all those martyred with him, and all from his progeny who followed him.”

And Sayyedah Zaynab was the vessel of that divine reward — the one who carried it, preserved it, and scattered it like seeds across the Ummah.

The Woman Who Sat Upon the Throne of Victory

Her stand was not symbolic. It was strategic. She confronted not only Ibn Ziyad and Yazid, but history itself. She ensured that the world would not read Karbala as the end of the Ahl al-Bayt — but as the birth of their global ascendancy.

From the ashes of the tent, she rose to a pulpit. From the chains of captivity, she delivered sermons that shook the empires of men.

She showed, as the Quran promises:

وَلَا تَهِنُوا۟ وَلَا تَحْزَنُوٓا۟ وَأَنتُمُ ٱلْأَعْلَوْنَ إِن كُنتُم مُّؤْمِنِينَ

“Do not weaken or grieve, for you shall be the uppermost — if you are believers.”

— Quran, Surah Aal-e-Imraan (the Family of Imraan) #3, Verse #139

This is what she enacted. Not in a battlefield — but in courts, streets, chains, and public spaces. Her veil became her shield. Her voice became her sword.

Not a Witness, But a Warrior

Sayyedah Zaynab proved that the revolution of Husayn did not die with Husayn. She became its guardian — and in so doing, shattered the lie that women have no role in sacred history.

As Ayatollah Mutahhari once wrote:

اگر زینب کبری (سلاماللهعلیها) نبود، شاید قیام امام حسین (علیهالسلام) در همان کربلا دفن میشد و به تاریخ نمیرسید. زینب فقط راوی کربلا نبود، او معمار دوم کربلا بود

“Had it not been for Sayyedah Zaynab, perhaps the mission of Husayn would have been stifled and buried. She was not a narrator of Karbala. She was its co-architect.”

Her words, her presence, her resolve turned the battlefield into a banner — a living banner — that continues to fly above every voice of truth and every stand of resistance.

The Sermon in Kufa

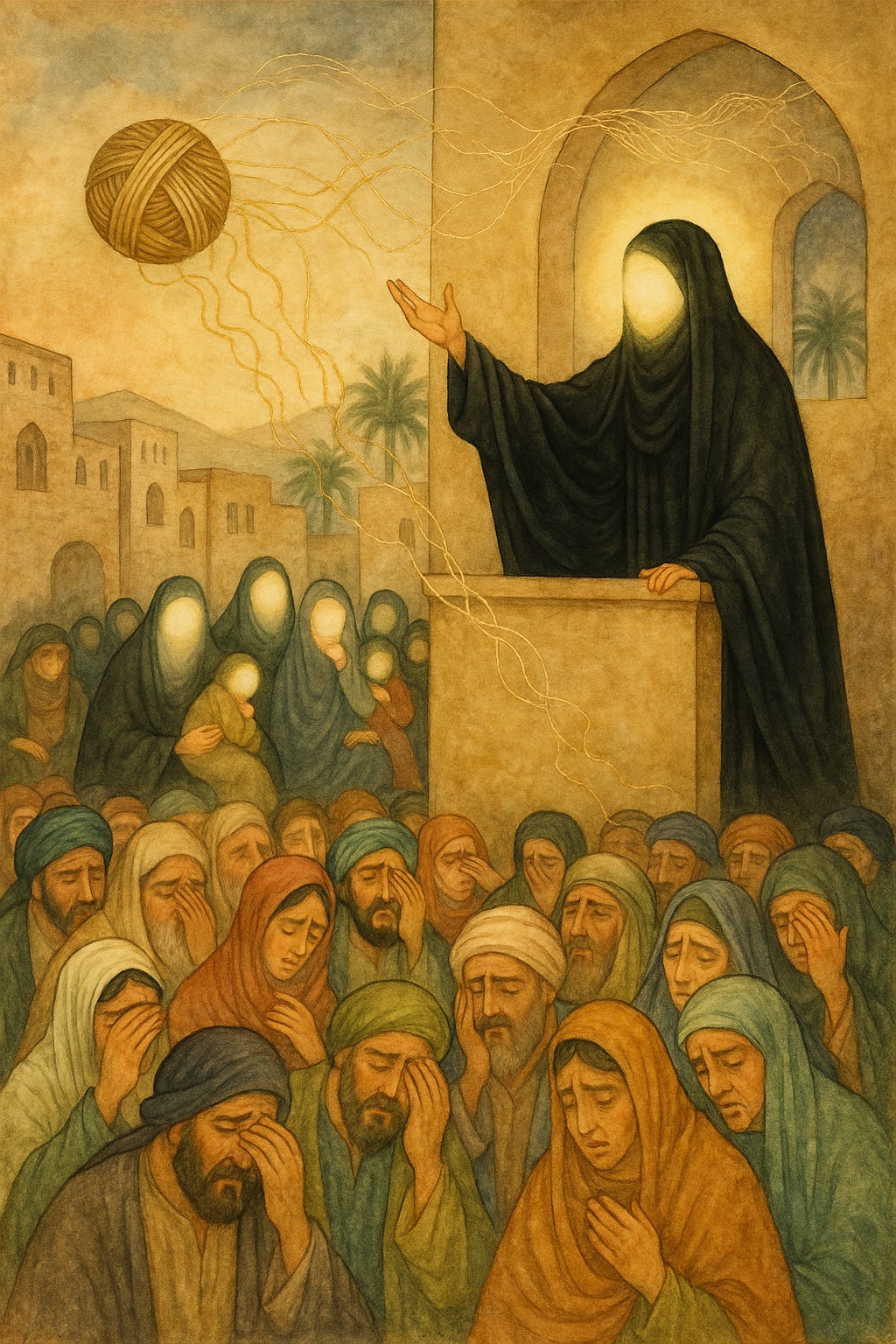

The Sermon That Shook a City of Hypocrisy

Kufa. A city that had once written letters of allegiance to Imam Husayn (peace be upon him), and then sealed its betrayal in blood. As the captives were paraded through its streets — veiled women humiliated, children crying, heads of martyrs mounted on spears — the people stood in silent shame. Some wept. Others rejoiced.

But Sayyedah Zaynab al-Kubra (peace be upon her) silenced them all.

From atop the platform of oppression, she delivered a sermon so piercing, it revived the very conscience of a collapsing society. It was not simply a speech — it was an indictment.

She began:

يَا أَهْلَ الْكُوفَةِ! يَا أَهْلَ الْخَتْلِ وَالْغَدْرِ! أَتَبْكُونَ؟ فَلَا رَقَأَتِ الدَّمْعَةُ، وَلَا هَدَأَتِ الرَّنَّةُ!

“O people of Kufa! O people of deception and betrayal! Do you weep? May your tears never dry, and your moaning never cease!”

This was not theatrical rhetoric. It was Quranic thunder in the voice of a woman. Her tone mirrored her father — the Commander of the Faithful, Imam Ali — and her language bore the clarity and severity of divine truth.

A Mirror to the Soul of the Faithless

She did not address the enemy with courtesy. She addressed the false friends — the ones who claimed to follow the Ahl al-Bayt, who imagined themselves pious, yet folded at the moment of truth. She rebuked them using the very words of the Quran:

كَٱلَّتِى نَقَضَتْ غَزْلَهَا مِنۢ بَعْدِ قُوَّةٍ أَنكَـٰثًۭا

“Like her who unravels her yarn after it was strongly spun.”

— Quran, Surah an-Nahl (The Chapter of the Bee) #16, Verse #92

She rebuked them saying:

يَا أَهْلَ الْكُوفَةِ، أَتَبْكُونَ وَلَا دَمْعٌ لَكُمْ؟! إِنَّمَا مَثَلُكُمْ كَمَثَلِ الَّتِي نَقَضَتْ غَزْلَهَا مِنْ بَعْدِ قُوَّةٍ أَنْكَاثًا، تَتَّخِذُونَ أَيْمَانَكُمْ دَخَلًا بَيْنَكُمْ

O people of Kufa! Do you weep when you have no tears?! Your example is like she who undoes her yarn after [spinning it to] strength, [making it] shreds. You take your oaths as deception between yourselves.

— Al-Majlisi38, Bihar al-Anwar39, Volume 45, PAge 114

— Al-Mufid40, Al-Irshad41, Volume 2, Page 121

— Al-Qummi42, Nafas al-Mahmum43, Page 291

— Al-Tayfur44, Balaghat al-Nisa45, Page 33

Her sermon was an x-ray. It showed that beneath the piety of Kufa lay cowardice. That behind the slogans was surrender. That loyalty without sabr (fortitude) is hypocrisy.

A Woman Who Silenced Tyranny

When the Tyrant is Shamed by the Veiled

Sayyedah Zaynab (peace be upon her) stood not in a hall of justice, nor among sympathisers. She stood in the marketplace of Kufa, surrounded by those who had betrayed her brother, delivered his companions to death, and now gawked at his surviving women and children like spoils of war.

And yet — she did not whisper. She roared.

In her voice was the echo of divine wrath and sacred grief. With no army at her back, she rendered the Yazidi system morally bankrupt. She spoke to the people as if she stood atop the pulpit of her father, Imam Ali, delivering not rebuke alone — but judgement.

أَتَبْكُونَ وَتَنْدُبُونَ أَنْفُسَكُمْ؟ فَوَاللهِ مَا مَثَلُكُمْ إِلَّا كَمَثَلِ ٱلَّتِي نَقَضَتْ غَزْلَهَا مِنۢ بَعْدِ قُوَّةٍ أَنكَـٰثًۭا

“Do you weep and wail for yourselves? By God, your likeness is that of her who unravels her yarn after it was firmly spun.”

This was not mere poetry. It was revelation, wielded like a sword. She knew her audience — people who had shouted “Labbayk!” and written pledges, but hid in their homes when Imam Husayn called for help.

Unmasking the Pretenders of Faith

Her sermon pierced the illusion of righteousness that cloaked the city of Kufa. She exposed the disconnect between tongue and heart — between slogans and perseverance (sabr).

لَا يَسْتَوِىٰ ٱلْقَـٰعِدُونَ مِنَ ٱلْمُؤْمِنِينَ… وَٱلْمُجَـٰهِدُونَ فِى سَبِيلِ ٱللَّهِ

“Not equal are those of the believers who sit back… and those who strive in the way of God.”

— Quran, Surah al-Nisa (The Chapter of the Women) #4, Verse #95

Sayyedah Zaynab unveiled this inequality with words. She told them:

أَتَزْعُمُونَ أَنَّكُمْ لِأَهْلِ بَيْتِ نَبِيِّكُمْ نَاصِرُونَ؟ فَلَمَّا أَتَاكُمُ الْحُسَيْنُ خَذَلْتُمُوهُ، وَبِعْتُمُوهُ بِالثَّمَنِ الْأَبْخَسِ، وَأَسْلَمْتُمُوهُ لِلْقَتْلِ! أَيْنَ زَعْمُكُمْ؟ أَيْنَ دِينُكُمْ؟

Do you claim to be supporters of your Prophet's household? Yet when Husayn came to you, you abandoned him, sold him for the cheapest price, and surrendered him to slaughter! Where is your claim? Where is your religion?

— Al-Majlisi48, Bihar al-Anwar49, Volume 45, Page 112

— Al-Mufid50, Al-Irshad51, Volume 2, Page 123

More Than a Martyr’s Sister

This was not a grieving woman venting emotion. This was an Imam-like figure, establishing hujjah — binding proof — upon a community that had no excuse.

She silenced them not by force, but by truth. And that is always the more terrifying power.

Her sermon did not end with condemnation — it ended with clarification. She gave them a mirror, and in it, they saw the decay of their own souls. Her voice rose from grief into guidance — a divine lecture in the clothes of captivity.

A New Archetype in the History of Islam

This is where her greatness is truly known: She rewrote the role of the veiled woman in history. She proved that the hijab is not silence — it is sanctity. That femininity is not weakness — it is moral clarity. And that leadership does not require office — it requires conviction.

With her sermon, she created a blueprint for resistance. Not with a sword, but with perseverance (sabr). Not in the battlefield, but in the marketplace. Not through soldiers, but through souls.

The Mission of Imam Sajjad During Captivity

The Silent Lion of Karbala

Amid the ruins of Karbala and the smoke of burning tents, there remained one man — too weak to lift a sword, too ill to rise, yet chosen by God to carry the Imamah forward. That man was Ali ibn al-Husayn Zayn al-Abedeen (peace be upon him), the fourth Imam of the Muslims.

His body was shackled. His back was bent by illness. Yet his spirit was unshaken. Just as Sayyedah Zaynab carried the message of Ashura with her voice, Imam Sajjad carried it with his presence — regal, composed, bearing divine authority even in chains.

The Quran affirms:

وَجَعَلْنَـٰهُمْ أَئِمَّةًۭ يَهْدُونَ بِأَمْرِنَا وَأَوْحَيْنَآ إِلَيْهِمْ فِعْلَ ٱلْخَيْرَٰتِ…

“We made them Imams, guiding by Our command, and We inspired them to do good works…”

— Quran, Surah al-Anbiya (the Chapter of the Prophets) #21, Verse #73

Even in captivity, he was guiding. Even in silence, he was speaking.

The Imam of the Captives

Imam Sajjad was not only preserving the biological survival of the Prophet’s family — he was protecting its spiritual mandate. The women and children looked to him. The message of Karbala lived through him.

As Sayyed Ibn Tawus52 notes in Al-Luhuf53, it was Imam Sajjad who:

Tended to the wounded

Kept morale among the captives

Defended the sanctity of the Ahl al-Bayt

And prepared to deliver the khutbah that would awaken Damascus

He was not merely Imam in name — he was Imam in function: a guide, a pillar, a living hujjah.

Imam as-Sadiq, quoted the Prophet (peace and blessings be upon him and his family) who said:

مَنْ أَصْبَحَ وَلَمْ يَهْتَمَّ بِأُمُورِ الْمُسْلِمِينَ فَلَيْسَ مِنْهُمْ

“Whoever awakens without concern for the affairs of the Muslims is not one of them.”

— Al-Kulayni54, Al-Kafi55, Volume 2, Book of Faith and Disbelief, Page 164, Hadeeth #12

No one in that era carried more haml — concern — than Imam Sajjad. Despite chains, weakness, and surveillance, he shepherded the flame of Islam through the abyss.

The Sermon in Damascus and the Pulse of Revolution

The Captive Who Exposed the King

In the lavish court of Yazid — surrounded by jesters, poets, and generals drunk on blood and conquest — Imam Zayn al-Abedeen (peace be upon him) stood, bruised, shackled, and visibly ill. And yet, in that moment, it was he who looked like the king, and Yazid who appeared as the disgraced criminal.

Yazid, seeking to parade his victory, permitted the young Imam to speak — confident that a chained, orphaned captive would have no power to move the crowd.

But what emerged from Imam Sajjad’s lips was not just a sermon — it was a theological earthquake. With eloquence and divine authority, he reintroduced the Ahl al-Bayt to the people of Damascus — a people long fed on lies by the Umayyad propaganda machine.

The Sermon that Reclaimed the Legacy

Imam Sajjad ascended the pulpit and began with praise of God and salutations upon the Prophet. Then, he introduced himself — not with lineage alone, but with legacy:

يَا أَيُّهَا النَّاسُ، أُعْطِينَا سِتًّا وَفُضِّلْنَا بِسَبْعٍ: أُعْطِينَا الْعِلْمَ، وَالْحِلْمَ، وَالسَّمَاحَةَ، وَالْفَصَاحَةَ، وَالشَّجَاعَةَ، وَالْمَحَبَّةَ فِي قُلُوبِ الْمُؤْمِنِينَ. وَفُضِّلْنَا بِأَنَّ مِنَّا النَّبِيَّ الْمُخْتَارَ، وَالصِّدِّيقَ، وَالطَّيَّارَ، وَأَسَدَ اللَّهِ، وَأَسَدَ رَسُولِهِ، وَسِبْطَيْ هَذِهِ الْأُمَّةِ.

أَنَا ابْنُ مَكَّةَ وَمِنًى، أَنَا ابْنُ مَنْ حُمِلَ عَلَى الْبُرَاقِ، أَنَا ابْنُ مَنْ أُسْرِيَ بِهِ مِنَ الْمَسْجِدِ الْحَرَامِ إِلَى الْمَسْجِدِ الْأَقْصَى، أَنَا ابْنُ مَنْ بَلَغَ بِهِ جَبْرَئِيلُ إِلَى سِدْرَةِ الْمُنْتَهَى...O people! We were given six [virtues] and preferred with seven:

We were given knowledge, forbearance, generosity, eloquence, courage,

And love in the hearts of believers.

And we were preferred by having among us:

The Chosen Prophet (Muhammad),

the Truthful One (Ali),

the Flyer (Ja'far al-Tayyar),

the Lion of God (Hamza),

the Lion of His Messenger (Ali),

and the two grandsons of this nation (Hasan and Husayn).

I am the son of Makkah and Mina.

I am the son of he who was carried upon the Buraq.

I am the son of he who was taken by night from the Sacred Mosque to al-Aqsa.

I am the son of he whom Jibril brought to the Lote Tree of the Utmost Boundary...

— Al-Majlisi56, Bihar al-Anwar57, Volume 45, Page 133

— Al-Mufid58, Irshad59, Volume 2, Page 135

And with each line, the crowd stirred. Tears flowed. Whispers spread. The veil of Yazid’s deception began to tear — thread by thread.

From Pulpit to Protest

By the end of the sermon, the tide had turned. People began to cry out:

أَخْزَى اللَّهُ يَزِيدَ!

“May God disgrace Yazid!”

The very man who had marched the captives as trophies now stood morally defeated by a sermon. And Yazid — rattled, humiliated — ordered the adhan to be called in a desperate attempt to silence the Imam.

But even then, Imam Sajjad replied with a final blow:

When the muadhin reached:

أشهد أن محمدًا رسول الله

“I bear witness that Muhammad is the Messenger of God”

The Imam turned to Yazid and said:

يَا يَزِيدُ، مُحَمَّدٌ هَذَا جَدِّي أَمْ جَدُّكَ؟ فَإِنْ زَعَمْتَ أَنَّهُ جَدُّكَ فَقَدْ كَذَبْتَ، وَإِنْ زَعَمْتَ أَنَّهُ جَدِّي، فَلِمَ قَتَلْتَ عِتْرَتَهُ؟

“O Yazid, is this Muhammad my grandfather or yours? If you claim he is your grandfather, then you lie. And if you admit he is mine — then why did you kill his family?”

This question was not just rhetorical — it was explosive.

Yazid had no answer. And from that moment, Damascus — the capital of Umayyad power — became uneasy.

The seeds of rebellion were sown.

A Revolution in Chains

The Imam had no army. No banners. No swords. Yet, his word was sharper than steel. He planted in the hearts of the people a truth that could not be killed: that the blood of Husayn was not spilt in vain, and that the Ahl al-Bayt were still the divinely appointed custodians of Islam.

As the Quran affirms:

ٱلَّذِينَ يُبَلِّغُونَ رِسَـٰلَـٰتِ ٱللَّهِ وَيَخْشَوْنَهُ وَلَا يَخْشَوْنَ أَحَدًا إِلَّا ٱللَّهَ

“Those who convey the messages of God and fear Him, and do not fear anyone but God.”

— Quran, Surah al-Ahzaab (the Chapter of the Confederates) #33, Verse #39

Imam Sajjad, though captive, conveyed the message in full — and rekindled the flame of faith amidst a palace of falsehood.

The Shia Condition After Karbala

Fear and Fragmentation: The Ummah in the Shadow of Karbala

After the massacre of Karbala, the landscape of the Islamic world — especially within the Shia community — was marred by fear, confusion, and fragmentation.

The event had exposed not only the cruelty of Yazid’s regime but also the fragility of the Muslims’ commitment to truth when faced with tyranny.

In Iraq, particularly in Kufa — the city that had once been the capital of Imam Ali (peace be upon him) — grief was met with guilt. Those who had invited Imam Husayn to rise had either betrayed him or remained paralysed in cowardice. In Madinah, hearts were broken, but resistance had not yet materialised. The Umayyads had succeeded — not only in silencing the voice of Husayn, but in spreading paralysis among the lovers of Ahl al-Bayt.

The Quran warns of such states:

فَخَلَفَ مِنۢ بَعْدِهِمْ خَلْفٌ أَضَاعُوا۟ ٱلصَّلَوٰةَ وَٱتَّبَعُوا۟ ٱلشَّهَوَٰتِ فَسَوْفَ يَلْقَوْنَ غَيًّۭا

Then there succeeded them a generation who neglected prayer and followed desires. So they shall soon face ruin.

— Quran, Surah Maryam (the Chapter of Saint Mary) #19, Verse #59

The betrayal of Karbala was not only an act of politics — it was the spiritual abandonment of divine responsibility.

The Collapse of Shia Organisational Strength

Imam al-Sadiq described the bleak aftermath:

إِرْتَدَّ النَّاسُ بَعْدَ الْحُسَيْنِ إِلَّا ثَلَاثَةٌ

The people turned back [from the religion] after Husayn — except three.62

In another narration, the Imam includes a handful more — sometimes five, sometimes seven. The exact number was small — painfully small — highlighting that in the wake of Karbala, the Shia movement was shattered, disorganised, and gripped by despair.

Imam as-Sadiq was reported to have said:

لَا يُوجَدُ فِي مَكَّةَ وَالْمَدِينَةِ عِشْرُونَ رَجُلًا يُحِبُّنَا

“There are not even twenty men in Makkah and Madinah who truly love us.”

— Al-Majlisi65, Bihar al-Anwar66, Volume 46, Page 143

— Ibn Abi al-Hadid67, Sharh Nahjul Balagha68, Volume 4, Page 104

This was the lowest ebb in the history of Shi’ism — a time when martyrdom had become so dangerous, so isolating, that even remembrance was criminalised.

But the Flame Still Burned

And yet, despite the terror, a pulse of resistance still flickered. In secret. In whispers. In coded poetry. The tragedy of Karbala had not destroyed the Shia — it had purified them. The traitors had fallen away. What remained were the sincere.

The first signs of organised resistance emerged even before Yazid’s death. Shia operatives working within Ibn Ziyad’s government smuggled messages to the prisoners in Kufa. One such report narrates a stone thrown into the prison courtyard with a note:

إِذَا سَمِعْتُمُ التَّكْبِيرَ فَاعْلَمُوا أَنَّ الْقَتْلَ قَدْ كُتِبَ عَلَيْكُمْ، وَإِلَّا فَقَدْ أَمِنْتُم

“If you hear the takbir (Allahu Akbar / God is the Greatest), know that you are to be executed. But if you do not hear it, you are safe.”

Even under surveillance, some believers risked everything to keep the Ahl al-Bayt informed and hopeful. This was not an organised army — but it was the beginning of what would one day become one.

Though Karbala left the Shia broken, it did not leave them defeated. Through mourning, memory, and quiet acts of defiance, they began to regroup. The path ahead would be steep and bloody — but the message of Imam Husayn would not be buried.

The Event of Harrah and Post-Ashura Repression

The Reign of Terror After Karbala: Madinah’s Day of Fire

Following the shockwaves of Karbala, the Umayyad regime, under Yazid ibn Muawiyyah, sought to extinguish every spark of resistance — not only in Kufa, but in the cradle of Islam itself: Madinah al-Munawwarah.

In 63 AH, an unprecedented atrocity occurred. The people of Madinah — many of them senior companions of the Prophet, children of the Ansar, and lovers of the Ahl al-Bayt — finally rose in protest against Yazid’s immoral rule. They had witnessed the blood of Husayn, they had heard of the captives paraded through Damascus, and they could no longer remain silent.

Their revolt was met with brutality. Yazid dispatched one of the most bloodthirsty commanders in Umayyad history — Muslim ibn Uqbah — with an army to crush the people of Madinah. The event became known as the massacre of Harrah.

A Massacre in the Prophet’s City

Muslim ibn Uqbah entered the sanctified city of Madinah — the city where the Prophet is buried — with his forces.

For three days, they pillaged, raped, looted, and massacred the population.

Ibn Qutaybah71 and others narrate:

قُتِلَ مِنْ أَهْلِ الْمَدِينَةِ مَا لَا يُحْصَىٰ، وَانْتُهِكَتِ الْحُرُمَاتُ، وَانْتُهِبَتِ الْأَمْوَالُ، وَصُلِّيَ فِي الْمَسْجِدِ بِغَيْرِ إِمَامٍ

“Countless were killed from the people of Madinah. Sanctities were violated. Wealth was plundered. And prayers were held in the Prophet’s Mosque without an Imam.”

— Ibn Qutaybah72, Al-Imamah wa al-Siyasah73, Volume 1, Page 194

— Al-Tabari74, Tarikh al-Tabari75, Volume 5, Pages 487-488

—Ibn Kathir76, Al-Bidayah al al-Nihayah77, Volume 8, Page 219

Even the sacredness of the Masjid al-Nabawi was desecrated. Over 700 noblemen were killed. Countless women were assaulted. Madinah — the radiant city of the Prophet — was turned into a battlefield of humiliation.

The Collapse of Morality Under Yazid

The people of Madinah had journeyed to Damascus in the early months of Yazid’s reign. They had witnessed his court, his drunkenness, his play with monkeys and dogs. When they returned, their eyes opened, they exposed him. It was this exposure that led to the massacre.

As Abdullah ibn Hanzalah said — the son of the martyr washed by angels in Uhud:

وَاللَّهِ مَا خَرَجْنَا عَلَىٰ يَزِيدَ حَتَّىٰ خِفْنَا أَنْ نُرْمَىٰ بِالْحِجَارَةِ مِنَ السَّمَاءِ، إِنَّهُ رَجُلٌ يَنْكِحُ الْأُمَّهَاتِ وَالْبَنَاتِ وَيَشْرَبُ الْخَمْرَ

“By God, we did not revolt against Yazid until we feared that stones would rain down upon us from the sky. He is a man who marries mothers and daughters, and drinks wine.”

A Purge Against the Lovers of Ahl al-Bayt

The aftermath of Harrah left the people of Madinah decimated. But most significant was the targeting of those sympathetic to the Ahl al-Bayt. From the noble families of the Ansar to the descendants of the Prophet, Yazid’s regime used this opportunity to purge any potential uprising.

It was a continuation of Karbala — not with swords against a caravan, but with spears against a city.

The Ripple Effect: Shia Silence in Kufa

At the same time, Shia efforts in Kufa were also suffering. The city that had once mobilised to support Imam Ali and later invited Husayn, was now browbeaten into fear. Secret gatherings were broken up. Movement leaders were executed or driven underground. Families that had supported the Ahl al-Bayt were isolated.

The Quran describes such moments:

إِنَّ الَّذِينَ فَتَنُوا الْمُؤْمِنِينَ وَالْمُؤْمِنَاتِ ثُمَّ لَمْ يَتُوبُوا فَلَهُمْ عَذَابُ جَهَنَّمَ وَلَهُمْ عَذَابُ الْحَرِيقِ

Indeed those who persecute the faithful, men and women, and do not repent thereafter, there is the punishment of hell for them and the punishment of burning."

— Quran, Surah al-Buruj (the Chapter of the Constellations) #85, Verse #10

The good — the lovers of truth — were now hunted.

Intellectual Decline and Moral Collapse in Makkah and Madinah

The Spiritual Ruin of the Sacred Cities

While Karbala bled and Madinah burned, Makkah and Madinah — the twin sanctuaries of Islam — were also suffering a less visible, but no less devastating, crisis: a collapse of religious seriousness and moral restraint.

The pulpits of divine guidance had been replaced with poetry of lust. The concern for wilayah and justice gave way to revelry, superstition, and spectacle.

In these sacred cities, where once the Prophet (peace and blessings be upon him and his family) recited the Quran and the Ahl al-Bayt led prayer, music and indulgence now filled the nights. The Umayyads had not only spilled blood — they had contaminated souls.

Imam al-Sadiq warned:

إِذَا ظَهَرَتِ الْفَوَاحِشُ فِي أَهْلِ قَرْيَةٍ وَهُمْ يُجَاهِرُونَ بِهَا، أَمِنُوا الْبَلَاءَ، فَيَعُمُّهُمُ اللَّهُ بِالْعِقَابِ

“When obscenities appear in a town and its people publicly engage in them, they feel secure — but God will strike them all with punishment.”

— Al-Kulayni80, Al-Kafi81, Volume 2, Page 276, Chapter “On the People Who Commit Sins Openly”

The Rise of the Minstrels and the Decline of Meaning

Abu al-Faraj al-Isfahani’s82 Kitab al-Aghani83 records that by the 70s and 80s AH, the most notorious musicians, drunkards, and poets of promiscuity resided not in Damascus — but in Makkah and Madinah.

Whenever the caliph grew bored in Damascus, he would dispatch envoys to find a singer, poet, or entertainer from these two cities.

The birthplaces of Quranic revelation had become the Umayyad entertainment districts.

The poet Umar ibn Abi Rabi’ah84 — infamous for his erotic verse — was beloved in Makkah. At his death, mourning filled the streets. Men and women alike wailed as though they had lost a prophet.

One bondwoman, upon being told not to cry, said:

الحمد لله الّذي لم يُخلِ الكعبة

“Praise be to God who has not left the Kabah empty.”

Her consolation? Another lascivious poet would take his place.

Mocking Revelation, Displacing the Prophet

The situation was not limited to the arts. Even theology was desecrated. The likes of Khalid ibn Abdullah al-Qasri87, a brutal Umayyad governor, would say:

الْخِلَافَةُ أَفْضَلُ مِنَ النُّبُوَّةِ

“The caliphate is greater than prophethood.”

This was not metaphor. It was ideological deviation. The Umayyads began to call their rulers Khalifat Allah — “the Caliph of God” — rather than “Caliph of the Messenger of God.”

This shift was intentional: to erase the Prophet’s centrality and replace it with their own.

Even in poetry, this doctrine seeped in:

يا بني أُميّة، إنَّ الخليفة هو خليفة الله، لا خليفة محمد

“O sons of Umayyah, the caliph is the Caliph of God, not the Caliph of Muhammad.”

—Al-Mas‘udi90, Muruj al-Dhahab91, Volume 3, Page 154

—Ibn Abi al-Hadid92, Sharh Nahjul Balagha93, Volume 4, Page 63

—Al-Kulayni94, Al-Kafi95, Volume 8, The Book of the Garden

—Subhani96, The Umayyad Ideology of Power97, Chapter “Divine Kingship vs Prophetic Succession”

When Sacredness Becomes Hollow

In one incident, Aisha bint Talha98, was performing tawaf (circumambulation) around the Kabah.

وكان خالد بن عبد الله القسري والي مكة يُعجَب بها، فكانت تطوف بالبيت، فأمر أن لا يُؤذّن للظهر حتى لا ينصرف الناس فيقطعوا عليها طوافها. فقيل له في ذلك، فقال: "لو طافت إلى الصباح ما أمرت أن يُؤذّن".

Khalid ibn Abdullah al-Qasri99, the governor of Makkah, was infatuated with her (Aisha bint Talha100). She was performing Tawaf around the Ka’bah, so he ordered that the Dhuhr adhan not be called so that people would not disperse and interrupt her Tawaf. When he was criticised for this, he said: 'Even if she were to circle until dawn, I would not order the Adhan to be called.’

— Al-Mizzi101, Tahdhib al-Kamal fi Asma al-Rijal102, Volume 35, Page 276

This was the state of Makkah — once the Qiblah of the righteous, now the playground of the powerful.

The Quran warns of such degeneration:

وَمَا كَانَ صَلَاتُهُمْ عِندَ ٱلْبَيْتِ إِلَّا مُكَآءًۭ وَتَصْدِيَةًۭ ۚ فَذُوقُوا۟ ٱلْعَذَابَ بِمَا كُنتُمْ تَكْفُرُونَ

“Their prayer at the House was nothing but whistling and clapping — so taste the punishment for what you used to deny.”

— Quran, Surah al-Anfaal (the Chapter of the Spoils (of War)) #8, Verse #35

This was the world Imam Sajjad inherited: Madinah in ruins, Makkah corrupted, the Shia broken, and the Umayyad regime seeking to erase all memory of Husayn.

But from that very darkness, the light of wilayah would be rekindled — through dua, through whispered knowledge, and through the eternal mourning for Ashura.

Conclusion

The Torchbearers of Karbala

Karbala did not end with martyrdom. It began with it. And from its blood-soaked soil rose two unparalleled inheritors of its mission: Sayyedah Zaynab al-Kubra and Imam Zayn al-Abedeen (peace be upon them both). One stood without a sword and shattered empires. The other, in silence and chains, planted the seeds of revival.

Sayyedah Zaynab’s greatness was not in lineage, but in her clarity of purpose. She walked beside Imam Husayn with eyes open and heart surrendered.

She stood in the ashes of the camp and became the refuge of the oppressed.

She entered the court of the tyrants and, with words alone, reduced their thrones to dust.

She is not merely the sister of a martyr. She is the preserver of his revolution, the voice of his blood, the continuation of his proof (hujjah). She proved that in the divine system, woman is not peripheral to resistance — she is central to it.

And Imam Sajjad — the captive, the orphan, the ill Imam — was not broken by grief. He carried the divine burden in silence and pain, with perseverance and fortitude (sabr) that defied swords and duas that revived souls.

When his family was paraded like criminals, he taught dignity. When his enemies sought to erase Husayn, he named him on the pulpit of Yazid.

As the Quran promised:

وَيُرِيدُ ٱللَّهُ أَن يُحِقَّ ٱلْحَقَّ بِكَلِمَـٰتِهِۦ وَيَقْطَعَ دَابِرَ ٱلْكَـٰفِرِينَ

“And God intends to establish the truth by His words and to cut off the root of the disbelievers.”

— Quran, Surah al-Anfaal (the Chapter of the Spoils (of War)) #8, Verse #7

Sayyedah Zaynab and Imam Sajjad were those words. Through them, truth was not silenced — it roared.

A Legacy for Every Age

They taught us that:

Victory is not in numbers, but in truth.

Strength is not in weapons, but in steadfastness (sabr).

Leadership is not in titles, but in sacrifice.

Revolution is not always with arms, but sometimes with tears, sermons, and prayer.

The Umayyads killed bodies — but could not kill the spirit of wilayah.

Sayyedah Zaynab ensured that Karbala would not be forgotten.

Imam Sajjad ensured that its message would be revived in every generation.

Their legacy is not history — it is ongoing duty.

And We, Today…

If we remember Imam Husayn, we must speak Sayyedah Zaynab’s truth.

If we wear black, we must stand as Imam Sajjad stood — with courage in chains and supplication on our lips.

The lesson of this session is simple and eternal:

Karbala lives — we have to but carry it.

A Supplication-Eulogy for the Night of Grief and the Dawn of Hope

In His Name, the Shelter of the Vulnerable

O God, send your blessings upon Muhammad and the Family of MuhammadO God…

O You who veil the trembling heart beneath the garment of Your gentleness,

O You who shelter the broken beneath the wing of Your mercy,

O You who watch over the frightened when no watchers remain…We call upon You tonight, not with strength but with shivers—

Not with titles, but with tears.You are the One who guarded Zaynab in the courts of the tyrants.

You are the One who gave strength to a neck bound in chains,

and dignity to a prisoner whose heart carried prophecy.O God…

When every veil was torn, You became her veil.

When every protector was slain, You became her shield.

When every voice was silenced, You made her tongue a sword.Zaynab — daughter of Ali, sister of Husayn, lioness of Karbala.

Zaynab — who stood, not for herself, but for You.And when they mocked her,

when they struck her,

when they paraded her through the streets of Kufa and Shaam,

You were the Witness.O Witness to every calamity, O Hearer of every groan, O Answerer of every plea...

O God…

And what of the chained Imam?

What of Ali ibn al-Husayn, whose back was scarred before it bent in age?

What of the eyes that saw the slaughter, and still returned to You in sajdah?O God, who gave him patience when the heart had shattered,

O God, who taught him to speak when the tongue was dry with grief,

O God, who made him the archive of Ashura and the author of whispers in the night…He wept not just for Husayn — but for us.

He spoke not just of Karbala — but of the future.

He cried not just for the past — but for the return.O God…

You did not abandon Zaynab.

You did not abandon Sajjad.

Do not abandon us.We are the fearful now.

Our time is a time of silence and masks —

Of hypocrites crowned and tyrants cheered.O God, the streets are again filled with chained believers,

and the voices of truth are dragged in your name.But we remember —

How You raised Zaynab above Yazid.

How You made her sermon louder than his throne.

How You turned the court of humiliation into the pulpit of defiance.So we plead to You…

Raise our heads again with the honour of conviction.

Give us tongues like Zaynab’s.

Give us the tears of Sajjad.

Give us the heart of Husayn.And bring us the one for whom they wept.

The son of the tearful, the awaited of the sorrowful.O God, hasten the relief of Your Wali, and make us among his helpers and supporters.

O God…

If we are to remain, let us remain in Your light.

If we are to rise, let it be for Your justice.

If we are to die, let it be in Your path.And if we are to live long…

let it be long enough to see his flag.Amen, O Lord of the fearful.

Amen, O Most Merciful of the merciful

And from Him alone is all ability and He has authority over all things.

Nahjul Balagha (Arabic: نهج البلاغة, "The Peak of Eloquence") is a renowned collection of sermons, letters, and sayings attributed to Imam Ali, the cousin and son-in-law of the Prophet Muhammad and the first Imam of the Muslims.

The work is celebrated for its literary excellence, depth of thought, and spiritual, ethical, and political insights. Nahjul Balagha was compiled by Sharif al-Radi (al-Sharif al-Radi, full name: Abu al-Hasan Muhammad ibn al-Husayn al-Musawi al-Sharif al-Radi), a distinguished Shia scholar, theologian, and poet who lived from 359–406 AH (970–1015 CE).

Sharif al-Radi selected and organised these texts from various sources, aiming to showcase the eloquence and wisdom of Imam Ali. The book has had a profound influence on Arabic literature, Islamic philosophy, and Shia thought, and remains a central text for both religious and literary study

See Note 1.

Abu al-Mufaddal Muhammad ibn Abd Allah ibn al-Muttalib al-Shaybani al-Kufi, commonly known as al-Khwarizmi (though not related to the famous mathematician), was a prominent Shia scholar of the 4th century AH (10th century CE) known for his significant contributions to the maqtal literature. Born and raised in Kufa, a center of Shia learning, al-Khwarizmi dedicated his life to collecting and compiling historical accounts related to the martyrdom of Imam Husayn. His Maqtal al-Husayn is one of the most comprehensive and influential works on the subject, drawing upon a wide range of early sources and narrations. Al-Khwarizmi's work is highly regarded for its detailed accounts of the events of Karbala, the biographies of the martyrs, and the sermons and speeches delivered by members of the Ahl al-Bayt. His Maqtal remains a central text in Shia mourning rituals and commemorations, preserving the legacy of Imam Husayn's sacrifice and inspiring generations of Shia Muslims.

Al-Khwarizmi's Maqtal al-Husayn stands as a cornerstone of Shia historical and devotional literature, offering a detailed and comprehensive account of the events surrounding the martyrdom of Imam Husayn at Karbala. Compiled in the 4th century AH (10th century CE), this maqtal draws upon a vast collection of early sources, narrations, and eyewitness accounts, meticulously assembled by al-Khwarizmi to provide a rich and multifaceted narrative. The work not only recounts the tragic events of Ashura but also delves into the lives and sacrifices of the companions of Imam Husayn, the sermons and speeches of the Ahl al-Bayt, and the profound spiritual and moral lessons derived from the Karbala narrative. Al-Khwarizmi's Maqtal al-Husayn is distinguished by its depth of detail, its commitment to preserving historical accuracy, and its enduring influence on Shia mourning rituals, making it an indispensable resource for understanding the significance of Imam Husayn's sacrifice and its lasting impact on Shia identity and spirituality.

Al-Allamah al-Muttaqi al-Hindi, whose full name is Ali ibn Husam al-Din al-Muttaqi al-Hindi (d. 975 AH/1567 CE), was a renowned Sunni scholar, hadeeth compiler, and jurist originally from Burhanpur in India. He traveled extensively in pursuit of knowledge, studying in Makkah, Madinah, and other centres of Islamic learning, and became known for his deep piety and scholarship. Al-Muttaqi al-Hindi’s most famous work is Kanz al-Ummal fī Sunan al-Aqwal wa al-Af’aal, a comprehensive hadeeth collection that gathers narrations from earlier sources, systematically arranged by topic. His compilation is highly regarded in both Sunni and Shia circles for its breadth and organisation, and it remains a valuable resource for scholars and students of Islamic tradition. Al-Muttaqi al-Hindi’s dedication to preserving the sayings and actions of the Prophet and his family has ensured his lasting influence in the field of hadeeth studies.

Kanz al-Ummal fī Sunan al-Aqwal wa al-Af’aal (كنز العمال في سنن الأقوال والأفعال), or "The Treasure of Workers in the Traditions of Sayings and Actions," is a monumental hadeeth collection compiled by Ali ibn Husam al-Din al-Muttaqi al-Hindi in the 10th century AH (16th century CE). This comprehensive work is a systematic arrangement of thousands of hadeeth narrations drawn from earlier, authoritative Sunni sources such as al-Jami al-Saghir of al-Suyuti and other prominent collections. Kanz al-Ummal is organised topically, making it easier for researchers and scholars to locate hadeeth related to specific subjects, ranging from theology and ethics to jurisprudence and history. The collection is valued for its breadth, organisation, and the inclusion of narrations that provide insights into the sayings, actions, and approvals of the Prophet Muhammad, as well as the practices of his companions, making it an indispensable resource for understanding Islamic tradition and jurisprudence.

Allamah Muhammad Baqir al-Majlisi (1037 AH / 1627 CE - 1110 or 1111 AH / 1698 or 1699 CE), a highly influential Shia scholar of the Safavid era, is best known for compiling Bihar al-Anwar, a monumental encyclopedia of Shia hadeeth, history, and theology that remains a crucial resource for Shia scholarship; he served as Shaykh al-Islam, promoting Shia Islam and translating Arabic texts into Persian, thereby strengthening Shia identity, though his views and actions, particularly regarding Sufism, have been subject to debate.

Bihar al-Anwar (Seas of Light) is a comprehensive collection of hadeeths (sayings and traditions of Prophet Muhammad and the Imams) compiled by the prominent Shia scholar Allamah Muhammad Baqir al-Majlisi.

This extensive work covers a wide range of topics, including theology, ethics, jurisprudence, history, and Quranic exegesis, aiming to provide a complete reference for Shia Muslims.

Allamah Majlisi began compiling the Bihar al-Anwar in 1070 AH (1659-1660 CE) and completed it in 1106 AH (1694-1695 CE), drawing from numerous sources and serving as a significant contribution to Shia Islamic scholarship.

Ayatullah Murtadha Mutahhari (1920-1979) was a prominent Iranian scholar, philosopher, and theologian, deeply influential in the intellectual development of the Islamic Revolution. Born in Fariman, Khorasan, he studied at the Qom Seminary under Imam Khomeini and Allamah Tabataba'i, excelling in Islamic philosophy and jurisprudence. Mutahhari authored numerous books on Islamic thought, ethics, and sociology, aiming to bridge traditional Islamic teachings with modern intellectual challenges. A key figure in shaping the ideological foundations of the Islamic Republic, he was assassinated in May 1979 shortly after the revolution's success, and is revered as a martyr and an intellectual leader in Iran.

See Note 9.

Hamase-ye Hosseini (The Epic of Husayn) by Ayatullah Murtadha Mutahhari is a seminal work in Shia Islamic literature, offering a profound analysis of the events surrounding the martyrdom of Imam Husayn at Karbala. The book delves into the historical, social, and philosophical dimensions of the Ashura narrative, aiming to dispel misconceptions and highlight the event's enduring significance for Muslims. Mutahhari emphasizes the importance of understanding the true message of Husayn's sacrifice, focusing on themes of justice, resistance against oppression, and the revival of Islamic values. Through a combination of scholarly analysis and eloquent prose, Hamase-ye Hosseini serves as a guide for contemporary Muslims to draw inspiration from the epic of Karbala and apply its lessons to their lives and societies.

See Note 7.

See Note 8.

Mirza Husayn Nuri Tabarsi, also known as al-Muhaddith al-Nuri, was a prominent Shia scholar and hadeeth compiler of the 19th and early 20th centuries. Born in 1254 AH (approximately 1838 CE) in the village of Nura, near Tabaristan, Iran, he dedicated his life to the study and dissemination of Islamic knowledge. He studied under distinguished scholars of his time, including Shaykh Abd al-Rahim al-Burujirdi and Mirza Muhammad Hasan Shirazi. Tabarsi is best known for his monumental work, Mustadrak al-Wasail, but he also authored numerous other books on various aspects of Shia theology, jurisprudence, and history. He passed away in 1320 AH (approximately 1902 CE) in Najaf, Iraq, where he is buried in the Imam Ali Shrine. His contributions to Shia scholarship continue to be valued and studied by researchers and students of Islamic studies.

Mustadrak al-Wasail wa Mustanbat al-Masail is a comprehensive collection of hadeeth compiled by Mirza Husayn Nuri Tabarsi. It serves as a supplement to the renowned Wasa'il al-Shia by Muhammad ibn Hasan al-Hurr al-Amili. Recognising that Wasa'il al-Shia, despite its extensive nature, did not encompass all available hadeeth, Tabarsi undertook the task of gathering additional narrations from various sources, including lesser-known and recently discovered texts. Mustadrak al-Wasail includes hadeeth that, while perhaps not meeting the stringent criteria of al-Hurr al-Amili, were deemed valuable for their content and potential contribution to Shia jurisprudence and understanding of Islamic teachings. The work is highly regarded in Shia scholarly circles for its thoroughness and the breadth of its sources.

Shaykh al-Kulayni (c. 864–941 CE / 250–329 AH), whose full name is Abu Jaʿfar Muhammad ibn Yaqub al-Kulayni al-Razi, was a leading Shia scholar and the compiler of al-Kafi, the most important and comprehensive hadeeth collection in Shia Islam.

Born near Rey in Iran around 864 CE (250 AH), he lived during the Minor Occultation of the twelfth Imam (874–941 CE / 260–329 AH) and is believed to have had contact with the Imam’s deputies.

Shaykh Al-Kulayni traveled extensively to collect authentic narrations, eventually settling in Baghdad, a major center of Islamic scholarship.

His work, al-Kafi, contains over 16,000 traditions and is divided into sections on theology, law, and miscellaneous topics, forming one of the "Four Books" central to Shia hadeeth literature.

Renowned for his meticulous scholarship and piety, Shaykh al-Kulayni’s legacy remains foundational in Shia studies, and he is buried in Baghdad, where he died in 941 CE (329 AH).

Al-Kafi is a prominent Shia hadeeth collection compiled by Shaykh al-Kulayni (see Note 1) in the first half of the 10th century CE (early 4th century AH, approximately 300–329 AH / 912–941 CE). It is divided into three sections:

Usul al-Kafi (theology, ethics),

Furu' al-Kafi (legal issues), and

Rawdat al-Kafi (miscellaneous traditions)

Containing between 15,000 and 16,199 narrations and is considered one of the most important of the Four Books of Shia Islam

See Note 7.

See Note 8.

Sayyed Radi al-Din Ibn Tawus (589 AH/1193 CE – 664 AH/1266 CE), a towering figure in Shia Islam, was a highly respected scholar, jurist, mystic, and prominent member of a distinguished scholarly family. Renowned for his piety, spiritual insights, and vast knowledge, he authored numerous influential works on jurisprudence, ethics, history, and, most notably, devotional practices, with his Iqbal al-Amaal standing as a cornerstone of Shia devotional literature. His deep understanding of Islamic teachings, coupled with his profound spiritual experiences, cemented his legacy as a guiding light for Shia Muslims seeking to deepen their connection with God and live a life of virtue and devotion.

Sayyed Ibn Tawus’s (d. 664 AH/1266 CE) Al-Luhuf alaa Qatla al-Tufuf (اللهوف علی قتلی الطفوف, "The Sorrows upon the Martyrs of Karbala") stands as one of the most poignant and enduring chronicles of Imam Husayn’s martyrdom. Composed in the 7th century AH, this concise yet emotionally charged maqtal (martyrdom narrative) distills the tragedy of Ashura with gripping intensity, blending historical reporting with theological reflection. Unlike lengthy academic works, Al-Luhuf was designed for public recitation during mourning gatherings, making it a cornerstone of Shia devotional practice. Ibn Tawus—a revered scholar and mystic—draws from early sources (some now lost) to present a heart-wrenching account, from the Imam’s departure from Medina to the captivity of the Ahl al-Bayt. Key passages, such as the angels’ lament ("Ya Muhammadah!") and Zaynab’s confrontation with Ibn Ziyad, are rendered with vivid imagery that has shaped Shia liturgical traditions for centuries. While the text lacks full chains of narration (isnaad), its theological alignment with Bihar al-Anwar and Maqtal al-Khwarazmi underscores its reliability. Today, Al-Luhuf remains a vital text for rawdah (elegy, mourning) reciters and scholars alike, bridging history and spirituality in the commemoration of Karbala’s eternal message.

Shaykh Abbas al-Qummi, also known as Muhaddith al-Qummi, was a prominent Shia scholar, historian, and hadeeth compiler of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Born in 1294 AH (approximately 1877 CE) in Qum, Iran, he dedicated his life to the study and propagation of Islamic knowledge. He studied under distinguished scholars such as Mirza Husayn Nuri Tabarsi, the author of Mustadrak al-Wasail. Qummi is best known for his works on history and biography, particularly his Nafas al-Mahmum and Muntaha al-Amal fi Tarikh al-Nabi wa al-Al, a comprehensive biography of the Prophet Muhammad and his family. He passed away in 1359 AH (approximately 1940 CE) in Najaf, Iraq, where he is buried in the Imam Ali Shrine. His works remain highly regarded and widely read in Shia scholarly and devotional circles.

Nafas al-Mahmum fi Musibat al-Husayn al-Mazlum is a renowned and influential work in Shia literature, written by Shaykh Abbas Qummi. This book meticulously chronicles the events surrounding the martyrdom of Imam Husayn at the Battle of Karbala. It serves as a comprehensive historical account and a profound expression of grief and mourning for the tragic events that befell the Prophet's family. Nafas al-Mahmum is widely recited during Muharram commemorations and is considered a significant source for understanding the historical and spiritual dimensions of the Karbala narrative, fostering deep emotional connection and reflection among Shia Muslims.

See Note 7.

See Note 8.

Attributed to Sayyedah Zaynab in Shia oral tradition, based on narrations of Karbala. See similar themes in:

Nafs al-Mahmum (نفس المهموم) by Sheikh Abbas al-Qummi (Chapter on Ashura)

Balaghat al-Nisa (بلاغات النساء) for Sayyedah Zaynab’s speeches

See Note 20.

See Note 21.

See Note 1.

See Note 20.

See Note 21.

See Note 7.

See Note 8.

See Note 9.

See Note 11.

See Note 7.

See Note 8.

See Note 7.

See Note 8.

Shaykh al-Mufid, Muhammad ibn Muhammad ibn al-Nu'man al-Baghdadi (336 AH/948 CE – 413 AH/1022 CE), was a prominent Shia theologian and jurist of the Buyid era. Born in the vicinity of Baghdad, he became a leading figure in the development of Shia thought, known for his expertise in kalam (Islamic scholastic theology) and fiqh (jurisprudence). Al-Mufid was a prolific writer, contributing significantly to the systematisation of Shia doctrine and law, and he trained numerous influential scholars, including Shaykh al-Tusi. His works, such as Kitab al-Irshad and al-Muqni'ah, remain central texts in Shia seminaries, solidifying his legacy as one of the most important and authoritative voices in Shia Islam.

Al-Irshad is one of the most celebrated works of Shaykh al-Mufid, serving as a foundational text in Shia scholarship. Written in the early 11th century CE, Al-Irshad provides detailed biographies of the twelve Imams of the Ahl al-Bayt, highlighting their spiritual virtues, historical roles, and the unique circumstances of their lives and martyrdoms. The book is valued not only for its historical narratives but also for its theological insights, as Shaykh al-Mufid draws upon both rational argument and transmitted reports to defend the doctrine of Imamah. Al-Irshad has been widely studied and referenced by later Shia scholars, and it continues to be a key source for understanding the lives and significance of the Imams within Twelver Shia Islam.

See Note 22.

See Note 23.

Abu al-Fadl Ahmad ibn Abi Tahir, known as al-Tayfur (204 AH/819 CE – 280 AH/893 CE), was a notable scholar and literary figure of the Abbasid era, recognised within Shia intellectual circles for his contributions to history and literature. Born in Baghdad, al-Tayfur's writings offer valuable perspectives on early Islamic society. Among his works, Balaghat al-Nisa (The Eloquence of Women) stands out as a collection of speeches, poems, and insightful sayings attributed to prominent women, including those from the Ahl al-Bayt and their devoted followers. This compilation provides a unique glimpse into the eloquence, wisdom, and steadfastness of women who played significant roles in the early history of Islam, particularly within the context of Shia Islam. Al-Tayfur's work serves as a testament to the intellectual and spiritual contributions of women in preserving and promoting the teachings of the Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him and his family) and the Imams.

Balaghat al-Nisa (The Eloquence of Women), compiled by Abu al-Fadl Ahmad ibn Abi Tahir al-Tayfur, is a unique and valuable collection of speeches, poems, and insightful sayings attributed to notable women in early Islamic history. This work is particularly significant within Shia circles as it includes accounts of the eloquence and wisdom of women from the Ahl al-Bayt, such as Sayyedah Fatima al-Zahra (peace be upon her) and Sayyedah Zaynab (peace be upon her). Balaghat al-Nisa offers a glimpse into the intellectual and spiritual contributions of these women, showcasing their profound understanding of Islamic teachings and their unwavering commitment to justice and truth. The book serves as an important resource for understanding the role of women in early Islamic society and their enduring legacy as exemplars of faith, courage, and eloquence within the Shia tradition.

See Note 7.

See Note 8.

See Note 7.

See Note 8.

See Note 40.

See Note 41.

See Note 20.

See Note 21.

See Note 16.

See Note 17.

See Note 7.

See Note 8.

See Note 40.

See Note 41.

See Note 7.

See Note 8.

The narration goes onto name those three individuals:

Abu Khalid al-Kabuli

Yahya ibn Umm Tawil

Jubayr ibn Mut’im

See Note 7.

See Note 8.

See Note 7.

See Note 8.

Husayn ibn Abi al-Hadid al-Mada'ini al-Iraqi, commonly known as Ibn Abi al-Hadid (586 AH/1190 CE – 656 AH/1258 CE), was a prominent Mu'tazilite scholar, jurist, and man of letters, highly regarded within Shia intellectual circles for his erudition and insightful commentary on the Nahjul Balagha. Born in Madain, near Baghdad, he served as a high-ranking official in the Abbasid administration while also producing significant works of literature and theology. Ibn Abi al-Hadid's most famous contribution is his extensive commentary on the Nahjul Balagha, which not only elucidates the eloquence and wisdom of Imam Ali (peace be upon him) but also reflects his own deep understanding of Islamic history, philosophy, and rhetoric. His commentary remains a cornerstone of Shia scholarship, valued for its comprehensive analysis and eloquent defence of Imam Ali's teachings.