[51] Mahdawiyyah (The Culminating Guidance) - The Four Deputies - Part 3 - The Diplomat in the Lion's Den

A series of discussions on the teachings of Imam Sadiq (sixth Imam of the Muslims), from the book Misbah ash-Sharia (The Lantern of the Path)

In His Name, the Most High

Introduction: The Cumulative Light

The Cumulative Structure

The series The Lantern of the Path is designed not merely as a historical anthology, but as a cumulative ladder—one cannot stand firmly on the later rungs if the foundational understanding of earlier stages is absent.

This approach mirrors the philosophical concept of Harakah al-Jawhariyyah (Substantial Motion), specifically the doctrine of the “Union of the Knower and the Known” (Ittihad al-Aqil wa al-Ma’qul).

In this view, knowledge is not a static collection of facts stored in the mind like items in a warehouse, but a dynamic existential process wherein the soul actually becomes the truth it comprehends.

فَإِنَّ النَّفْسَ ... تَصِيرُ عَقْلاً بِالْفِعْلِ ... وَ يَتَّحِدُ بِهَا الْمَعْقُولاتُ اتِّحَاداً وُجُودِيّاً

“For the soul... becomes an actual intellect... and the intelligibles unite with it in an existential union.”

— Mulla Sadra (Sadr al-Din al-Shirazi), Al-Hikmah al-Muta’aliyah fi al-Asfar al-Aqliyyah al-Arba’ah (The Transcendent Theosophy in the Four Journeys of the Intellect), Volume 3, Section on the Union of the Knower and the Known.

We are attempting to construct a Jahan Bini (Worldview)—a structured assembly of ideas rather than a collection of isolated narratives.

As Shaheed Mutahhari defines it, a worldview is the very foundation upon which a human being interprets reality:

جهانبينى يعنى نوع برداشت و طرز تفكرى كه يک مكتب يا يک فرد درباره جهان و هستى دارد

“Worldview means the type of perception and mode of thinking that a school of thought or an individual holds regarding the world and existence.”

— Shaheed Murtadha Mutahhari, Muqaddimah-i bar Jahan Bini-yi Islami (Introduction to the Islamic Worldview), Vol. 1: Insan va Iman (Man and Faith), Chapter: Definition of Worldview.

The Divine Injunction to Remind

The necessity of revisiting previous material—specifically the lives and strategies of the First and Second Deputies—is rooted in the recognition that human consciousness is prone to forgetfulness.

The act of returning to established truths serves to anchor them, transforming information into conviction.

This principle is explicitly stated in the Holy Quran, where God commands Prophet Muhammad, may peace and blessings be upon him and his family, to persist in the act of reminding:

وَذَكِّرْ فَإِنَّ الذِّكْرَىٰ تَنفَعُ الْمُؤْمِنِينَ

“And remind, for indeed, the reminder benefits the believers.”

— Quran, Surah Adh-Dhariyat (the Chapter of the Winnowing Winds) #51, Verse 55

Therefore, while a brief review of previous sessions on the “Hidden Network” may provide context, comprehensive engagement with those materials remains essential for grasping the full trajectory of the Minor Occultation, as well as the other subjects we’ve covered within the Lantern of the Path series.

These are subjects covered so that we may understand what servitude to God truly means—servitude being the central lesson we have sought to comprehend and embody since the very beginning of this epic journey.

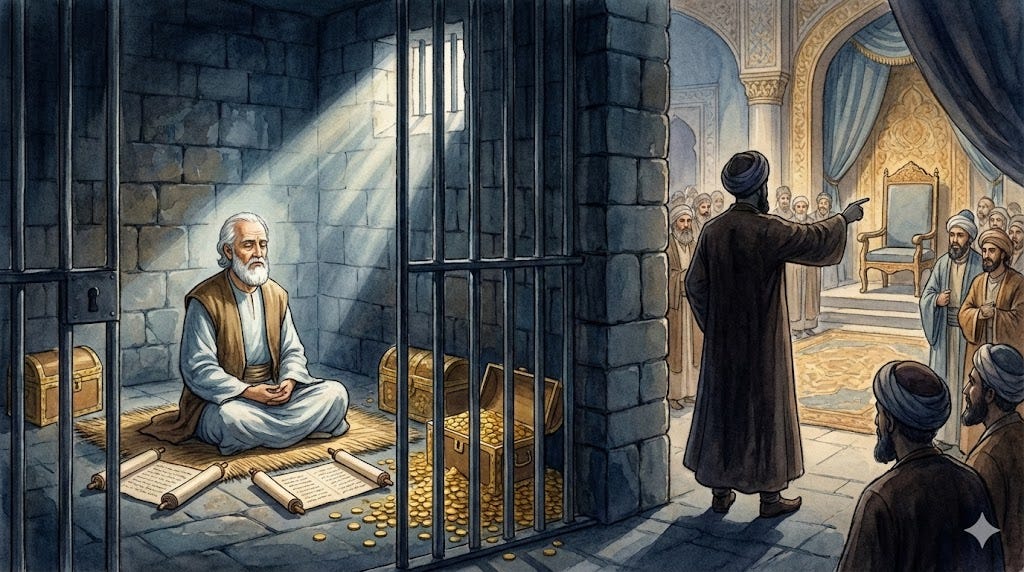

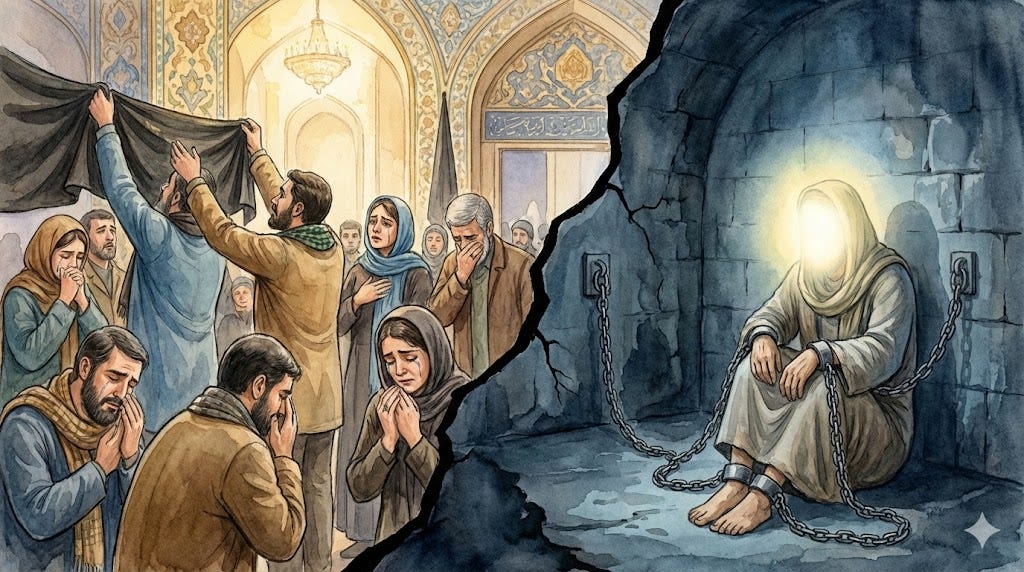

The Shift: From Shadow to Court

In this session, the narrative arc undergoes a dramatic shift.

Our previous analysis focused on the “Hidden Network” of the Second Deputy—a time of clandestine operations, secret agents, and the establishment of an underground economic infrastructure.

Tonight, we move from the cellar to the palace.

The trajectory shifts from concealment to visibility, from underground networks to high-stakes public diplomacy.

We now enter the world of the Third Deputy, Husayn ibn Ruh al-Nawbakhti—and with him, we approach the illuminated yet perilous court of the Abbasids.

In His name, we proceed.

We beseech Him to guide us, to grant us the ability (tawfiq) and strength, and to bestow upon us the patience (sabr) to walk in the footsteps of these luminaries.

By His grace and taking refuge in Him, we step into the Lion’s Den.

Video of the Majlis (Sermon/Lecture)

This is the video presentation of this write-up as a Majlis (part of the Truth Promoters Weekly Wednesday Majlis Program)

Audio of the Majlis (Sermon/Lecture)

This is the audio presentation of this write-up as a Majlis (part of the Truth Promoters Weekly Wednesday Majlis Program)

Recap: The Legacy of the Architect

The Transition from Person to Institution

In our previous session, we explored the life and legacy of the Second Deputy, Muhammad ibn Uthman al-Amri.

If the First Deputy was the “Crisis Manager” who saved the community from immediate collapse, the Second Deputy was the “Institution Builder.”

He served for nearly forty years—longer than any other deputy—and during this time, he transformed the Wikalah (The Agency) from a temporary emergency measure into a permanent, global infrastructure.

We established that his authority was derived not from biology, but from theology.

He was not chosen simply because he was the son of Uthman ibn Sa’id; he was chosen because he possessed the specific merit required to carry the burden.

This distinction dismantles the concept of dynastic monarchy and upholds the principle of Divine Selection based on capacity.

The Pillars of the Structure

Our analysis of his tenure—drawing on the insights of both Imam Khamenei and Ayatullah Shaheed Muhammad Baqir al-Sadr—revealed three structural pillars that sustain the Shia community to this day:

The Economics of Independence

Muhammad ibn Uthman institutionalised the collection of Khums (religious dues).

This was not merely a financial transaction, but a political strategy for sovereignty.

By establishing an independent treasury, the Deputy ensured that the religious scholars would never be beholden to the salaries of the Abbasid state.

As the political axiom states:

“He who feeds you, controls you.”

The Second Deputy secured the financial freedom of the faith, allowing the truth to be spoken without fear of state sanction.

The Government in Exile

He perfected the Tanzim al-Sirri (Secret Organisation).

Operating under the nose of a hostile surveillance state—mastering the art of Taqiyyah (Strategic Prudence) to the point where he appeared publicly as a respectable Sunni notable while serving secretly as the Gate to the Hidden Imam—he managed a network of agents spanning from Qom to Yemen, from Egypt to Khurasan.

This network functioned on a “need-to-know” basis, effectively serving as a government in exile.

It demonstrated that the community could remain united and disciplined even when its leader was invisible.

The Constitution of the Occultation

Perhaps his most enduring contribution was the delivery of the foundational Tawqi’ (signed letter) that established the legitimacy of the scholars during the Major Occultation.

When asked what the community should do regarding new problems once access to the Imam was severed, the reply came through Muhammad ibn Uthman:

وَأَمَّا الْحَوَادِثُ الْوَاقِعَةُ فَارْجِعُوا فِيهَا إِلَى رُوَاةِ حَدِيثِنَا، فَإِنَّهُمْ حُجَّتِي عَلَيْكُمْ وَأَنَا حُجَّةُ اللَّهِ عَلَيْهِمْ

“As for the newly occurring events (Al-Hawadith al-Waqi’ah), refer regarding them to the narrators of our traditions, for surely they are My Proof over you, and I am the Proof of God over them.”

— Al-Saduq, Kamal al-Din wa Tamam al-Ni’mah, Vol. 2, Chapter 45, Hadith 4

This document serves as the charter for the Marjaiyyah.

As Shaheed al-Sadr observed, the Minor Occultation was a training operation—preparing the community to transition from reliance on specific, named deputies to the general system of scholarly leadership that would guide them through the centuries ahead.

The Second Deputy was not building an empire around his own person; he was building a system that could function even after the door of specific appointment closed forever.

The Certainty of Departure

Finally, we witnessed the profound spiritual realism of the Second Deputy.

Years before his death, he dug his own grave inside his home.

He would descend into it, recite the Quran, and familiarise his body with the earth.

This act demonstrated that leadership in Islam is not a privilege to be enjoyed, but a trust to be discharged before the inevitable return to God.

Upon his deathbed in 305 AH, he did not leave the community in a vacuum.

By the specific command of the Hidden Imam—may our souls be his ransom—he appointed a man who would take this hidden network and project its influence into the very courts of power.

He passed the torch to Husayn ibn Ruh al-Nawbakhti.

Mahdawiyyah (The Culminating Guidance) - The Four Deputies - Part 3 - The Diplomat in the Lion’s Den

The Art of Strategic Presence: Diplomacy in the Court

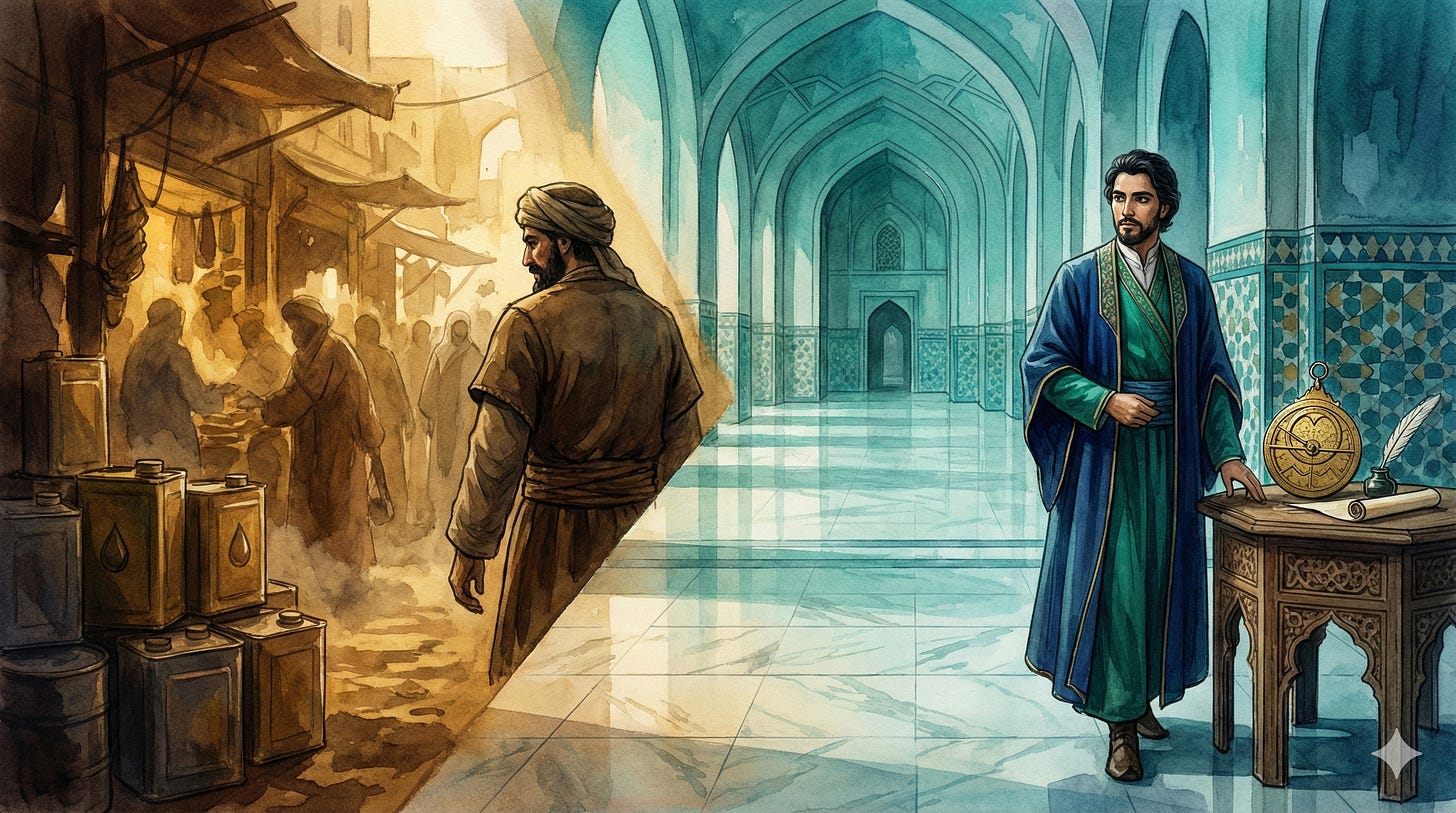

The Sociological Shift: From Marketplace to Palace

In analysing the transition from the Second Deputy to the Third, one observes a deliberate and profound shift in the sociological profile of the leadership.

The First and Second Deputies—Uthman ibn Sa’id and Muhammad ibn Uthman—operated under the cover of Samman (Oil Sellers).

Their operational base was the marketplace: the chaotic, noisy environment of the bazaar where they could blend in with common merchants, hiding the secrets of the Imamate inside canisters of cooking fat.

This tradecraft was necessary for the initial phase of the crisis, where anonymity served as the primary shield.

However, for the third phase of the Minor Occultation, the Imam selected a different instrument entirely.

He appointed Husayn ibn Ruh al-Nawbakhti.

The significance of his surname—al-Nawbakhti—cannot be overstated.

The Nawbakhtis were not oil sellers; they were the elite power-brokers of the Abbasid Golden Age.

They were a prominent Persian family of astronomers, theologians, and administrators who had converted from Zoroastrianism to Islam and risen to the highest echelons of the state.

They translated Greek philosophy, managed state bureaus, and dined with Viziers.

The biographical sources record their distinguished position:

كَانَتْ بَنُو نَوْبَخْتَ مَعْرُوفَةً بِالْوَلَاءِ لِأَهْلِ الْبَيْتِ (ع) مَعَ مَكَانَتِهِمُ الْمَرْمُوقَةِ فِي الدَّوْلَةِ الْعَبَّاسِيَّةِ وَاشْتِغَالِهِمْ بِالْكِتَابَةِ وَالنُّجُومِ وَالْفَلْسَفَةِ

“The Banu Nawbakht were known for their loyalty to the Ahl al-Bayt, peace be upon them, alongside their prestigious status in the Abbasid State and their occupation with administration, astronomy, and philosophy.”

— Al-Najashi, Rijal al-Najashi, Entry on the Nawbakhti family

By selecting a Nawbakhti, the Imam effectively moved the headquarters of the Resistance from the marketplace to the court.

He selected a man who could walk through the front door of the Caliph’s palace—not as a prisoner, but as a dignitary.

This marked a strategic pivot from “hiding from the state” to “operating within the state.”

The Theological Reframing: Taqiyyah as Strategic Power

To understand how Husayn ibn Ruh operated within the Abbasid administration while serving the Hidden Imam, one must correct a fundamental misunderstanding regarding the concept of Taqiyyah.

In popular discourse—and often in polemical attacks against the Shia—Taqiyyah is mistranslated as “dissimulation” or equated with fear and hypocrisy.

Theologically, this is incorrect.

The root of the word is Waqa, meaning “to shield” or “to guard.”

Taqiyyah is not passive fear; it is Strategic Prudence.

It is the discipline of the soldier who operates behind enemy lines, concealing his true allegiance not out of shame, but to protect the mission from eradication.

It requires a high degree of intellect (aql) to suppress the emotional urge to speak in favour of the strategic necessity to survive.

Imam Ja’far al-Sadiq establishes this link between Taqiyyah and faith explicitly:

لا دِينَ لِمَنْ لا تَقِيَّةَ لَهُ... وَالتَّقِيَّةُ تُرْسُ اللَّهِ بَيْنَ إِيَّاهُ وَبَيْنَ خَلْقِهِ

“There is no faith (Deen) for the one who has no Taqiyyah... And Taqiyyah is the Shield of God (Turs Allah) between Him and His creation.”

— Al-Kulayni, Al-Kafi, Vol. 2, Kitab al-Iman wa al-Kufr (Book of Faith and Disbelief), Chapter on Taqiyyah, Hadith 5

If a believer exposes the network or endangers the Imam because they lack the discipline to control their speech, they have not displayed courage—they have displayed a lack of faith.

The Unity of Method: Silence and Revolution

One might object:

"Is this silence not a betrayal of the revolutionary spirit of Karbala?

Did Imam Husayn not rise against the tyrant?

Why then does his representative hide within the tyrant's court?"

To answer this, we turn to the profound analysis of the martyred thinker, Shaheed Murtadha Mutahhari.

He argues that the behaviour of the Infallibles changes based on context, but their goal remains singular.

The “Silence” of one leader and the “Uprising” of another are not contradictions — they are the same religion manifested in different circumstances:

شکل مبارزه ممكن است تفاوت کند اما محتواى مبارزه یكی است. على (ع) همان حسین (ع) است در شرایط على، و حسین (ع) همان على (ع) است در شرایط حسین. گاهی سکوت، عین مبارزه است.

“The form of the struggle may differ, but the content of the struggle is one. Ali is the same as Husayn in the conditions of Ali; and Husayn is the same as Ali in the conditions of Husayn. Sometimes, silence is the very essence of struggle.”

— Shaheed Murtadha Mutahhari, Sayri dar Sireh-ye A’immah (A Survey of the Conduct of the Imams), Chapter: Solh-e Imam Hasan (The Peace of Imam Hasan)

Husayn ibn Ruh, then, represents a man who must carry the spirit of Imam Husayn while living in the court of the Yazid of his time—a task that requires a discipline often harder than drawing the sword itself.

The Strategy of Heroic Flexibility

This method of operating within a hostile system has been analysed by the Leader of the Islamic Revolution, Imam Khamenei, under the concept of “Heroic Flexibility” (Narmish-e Ghahramananeh).

This term serves as a modern articulation of the strategy employed by the Imams and their Deputies.

Imam Khamenei explains that flexibility in politics is not synonymous with surrender.

He utilises the metaphor of a wrestler who adjusts his stance or yields a position technically—not to forfeit the match, but to gain the necessary leverage for a decisive move:

نرمش قهرمانانه به معنای مانور هنرمندانه برای دست یافتن به مقصود است... کشتیگیری که دارد با حریف خود کشتی میگیرد و یک جایی به دلیل فنی نرمشی نشان میدهد، این نرمش را نباید به معنای عقبنشینی و دست برداشتن از اصول تصور کرد

“Heroic Flexibility (Narmish-e Ghahramananeh) means manoeuvring artistically to achieve the goal... A wrestler who is grappling with his opponent and shows flexibility at a certain point for a technical reason—this flexibility should not be imagined as a retreat or an abandonment of principles.”

— Imam Khamenei, Speech to Commanders and Personnel of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps, September 17, 2013 (26 Shahrivar 1392).

Historical Precedents: The Erasure of Title

This strategy is not an innovation of the Deputies; it is the Sunnah of the Prophet himself.

At the Treaty of Hudaybiyyah, when the Quraysh refused to sign the document because it began with

“Muhammad, Messenger of God,”

the Prophet, peace and blessings be upon him and his family, ordered Imam Ali to erase his own title — ”Messenger of God” — and replace it with

“Muhammad ibn Abdullah.”

The Companions were outraged.

They saw it as humiliation.

But the Prophet saw it as Victory (Fath).

He yielded the title to secure the treaty—a treaty that eventually led to the conquest of Makkah itself.

Similarly, Imam Hasan al-Mujtaba signed a treaty with Muawiyah—not out of weakness, but to preserve the blood of the believers and expose the true nature of the Umayyad regime to history.

Husayn ibn Ruh was walking in these very footsteps.

He erased his public claim to save the secret Truth.

He practised the “Treaty of Hudaybiyyah” in the palaces of Baghdad—yielding the verbal point to secure the survival of the believers.

Concept Clarification: Taqiyyah vs. Tawriyah

Before we witness how Husayn ibn Ruh applied this strategy in the court, we must clarify our terminology.

We have used two terms:

Taqiyyah and Tawriyah.

Are they the same?

No.

Taqiyyah is the Principle.

It is the obligation to protect the Truth from destruction—the shield that guards the mission.

Tawriyah is the Tactic.

It is the linguistic tool used to achieve that protection without speaking a falsehood.

It is the art of Strategic Ambiguity.

Critics often accuse the Shia of sanctioning lies.

But Tawriyah is not lying.

Lying is to say what is false.

Tawriyah is to say what is true, but in a way that the listener interprets according to their own expectations.

Shaheed Murtadha Mutahhari, in his analysis of Islamic ethics, distinguishes clearly between the two.

He argues that while lying is inherently corrupt, Tawriyah is an exercise of intelligence deployed to preserve the truth:

«... برای اینکه روحت عادت نکند به دروغ گفتن، در آنجا که اجبار پیدا میکنی، چیزی به ذهنت خطور بده و به زبانت چیز دیگری بیاور... اسم این “توریه” است... ذهنت را هرگز مستقیم با دروغ مواجه نکن که به دروغ گفتن عادت نکند.»

“...So that your soul does not become habituated to lying, in situations where you are compelled [to conceal the truth], let one meaning cross your mind while you bring something else to your tongue... The name of this is ‘Tawriyah’... Never confront your mind directly with a lie, so that it does not get used to lying.”

— Shaheed Murtadha Mutahhari, Falsafah-ye Akhlaq (The Philosophy of Ethics), Vol. 1, Page 88 (Sadra Publications). Section: Dorough-e Maslahat-amiz (Expedient Falsehood).

The Prophetic Precedent

This method is not a later theological invention; it is firmly rooted in the Seerah (Biography) of the Holy Prophet himself.

The most famous instance occurred during the Hijrah (Migration) to Madinah.

The Prophet and Abu Bakr were travelling through the desert, evading the bounty hunters of Quraysh.

An old Bedouin man encountered them and asked who they were and where they came from.

To reveal their identity meant death.

To claim they were from a different tribe would be a lie.

The Prophet replied with a single phrase:

نَحْنُ مِنْ مَاءٍ

“We are from water.”

The Bedouin, interpreting this through his tribal knowledge, assumed they meant they were from the tribe of “Ma’ al-Sama’” (a branch of the Azd tribe) or simply from a region known for its wells.

He let them pass.

But the Prophet intended the Quranic reality—that humanity itself is created from water:

وَجَعَلْنَا مِنَ الْمَاءِ كُلَّ شَيْءٍ حَيٍّ

“And We made from water every living thing.”

— Quran, Surah al-Anbiya (the Chapter of the Prophets) #21, Verse 30

He spoke the absolute Truth.

The listener heard what he expected to hear.

This is Tawriyah.

This event is recorded in the foundational historical texts of both Sunni and Shia scholarship, confirming its status as an undisputed Prophetic precedent:

From Sunni Sources:

قَالَ الرَّجُلُ: مِمَّنْ أَنْتُمَا؟ قَالَ رَسُولُ اللَّهِ صَلَّى اللَّهُ عَلَيْهِ وَسَلَّمَ: “نَحْنُ مِنْ مَاءٍ”. قَالَ ابْنُ هِشَامٍ: يَعْنِي أَنَّ اللَّهَ تَعَالَى خَلَقَ كُلَّ شَيْءٍ حَيٍّ مِنْ مَاءٍ.

“The man asked: ‘Who are you two from?’ The Messenger of God (peace be upon him) said: ‘We are from water.’ ... Ibn Hisham commented: He meant that God the Exalted created every living thing from water.”

— Ibn Hisham, Al-Sirah al-Nabawiyyah, Vol. 2, Page 488 (The Migration of the Messenger)

— Al-Tabari, Tarikh al-Umam wa al-Muluk, Vol. 2, Page 378

And from Shia Sources:

فَقَالَ لَهُ: مِمَّنْ أَنْتَ؟ فَقَالَ (ص): “مِنْ مَاءٍ”. فَأَرَادَ بِهِ قَوْلَهُ تَعَالَى: ﴿أَلَمْ نَخْلُقْكُمْ مِنْ مَاءٍ مَهِينٍ﴾.

“He asked him: ‘Who are you from?’ He (the Prophet) replied: ‘From water.’ By this, he intended the Word of the Exalted: ‘Did We not create you from a despised fluid (water)?’”

— Al-Majlisi, Bihar al-Anwar, Vol. 19, Page 83, citing Al-Khara’ij wa al-Jara’ih regarding the miracles of the Hijrah

This was the “wand” of words that Husayn ibn Ruh would wield in the Abbasid court.

He did not invent the strategy; he inherited it from the Prophet himself.

Historical Evidence I: The “Wand” of Diplomacy

The brilliance of Husayn ibn Ruh’s strategy—his mastery of Tawriyah (strategic ambiguity)—is best illustrated by a pivotal incident recorded by Shaykh al-Tusi in his Kitab al-Ghaybah (Book of the Occultation).

A gathering was convened in the presence of Abbasid officials and Sunni scholars.

The enemies of the Ahl al-Bayt were attempting to trap Husayn ibn Ruh into making a statement that would expose him as a Shia leader—a Rafidi in their terminology—which would lead to his execution and the dismantling of the entire network.

Husayn ibn Ruh preempted them.

In that crowded assembly, he rose and made a public declaration:

قَالَ الْحُسَيْنُ بْنُ رُوحٍ فِي مَجْلِسٍ حَافِلٍ: “أَجْمَعَ الْمُسْلِمُونَ عَلَى أَنَّ خَيْرَ هَذِهِ الْأُمَّةِ بَعْدَ نَبِيِّهَا صَلَّى اللَّهُ عَلَيْهِ وَآلِهِ وَسَلَّمَ: أَبُو بَكْرٍ، ثُمَّ عُمَرُ، ثُمَّ عُثْمَانُ، ثُمَّ عَلِيٌّ.” فَاسْتَحْسَنَ الْحَاضِرُونَ ذَلِكَ مِنْهُ وَأَثْنَوْا عَلَيْهِ، وَكَفَّ الْمُخَالِفُونَ عَنْ سِعَايَتِهِمْ بِهِ.

“Husayn ibn Ruh declared in a crowded gathering: ‘The Muslims have agreed by consensus (Ajma’a) that the best of this community after its Prophet—may the peace and blessings of God be upon him and his family—is Abu Bakr, then Umar, then Uthman, then Ali.’ The attendees approved of this from him and praised him, and the opponents ceased their malicious reports against him.”

— Shaykh al-Tusi, Kitab al-Ghaybah, Section: Akhbar Husayn ibn Ruh (Reports of Husayn ibn Ruh). Also cited in Al-Majlisi, Bihar al-Anwar, Vol. 51, Chapter on the Third Deputy

The Shia attendees were horrified.

They thought their Deputy had apostatised.

Some wept.

Others questioned whether the channel to the Imam had been severed.

How could the representative of the Hidden Imam utter such words?

Later, in private, the confused followers approached him.

They demanded an explanation.

His response reveals the precise calculus of survival:

فَقَالَ لَهُمْ: “وَيْحَكُمْ! إِنَّمَا قُلْتُ هَذَا لِأَدْفَعَ عَنْكُمُ السَّيْفَ، وَلَوْلَا ذَلِكَ لَقُتِلْتُ وَقُتِلْتُمْ.”

“He said to them: ‘Woe to you! I only said this to deflect the sword from you. Had it not been for that statement, I would have been killed, and you would have been killed.’”

— Shaykh al-Tusi, Kitab al-Ghaybah, Section: Akhbar Husayn ibn Ruh

Notice the precision of his original statement.

He did not say:

“I believe that the best of this community is Abu Bakr...”

He said:

“The Muslims have agreed by consensus that the best of this community is...”

This is Tawriyah—the art of strategic ambiguity.

He stated a fact about what the majority of Muslims publicly claimed to believe.

The Sunni officials heard it as a personal confession of faith.

But the statement itself was a description of public opinion, not a declaration of his own heart.

He used the “wand” of words to deflect the physical sword of the tyrant.

He performed the verbal equivalent of the Treaty of Hudaybiyyah: yielding the point of public declaration to secure the survival of the believers.

Just as the Prophet erased his own title to secure the treaty that would lead to victory, Husayn ibn Ruh swallowed words that burned in his throat to keep the network alive.

This was not a personal choice.

It was a binding religious obligation mandated by the Infallible himself.

Imam Ali ibn Musa al-Ridha established both the requirement and its duration:

قَالَ عَلِيُّ بْنُ مُوسَى الرِّضَا (عليه السلام): “لا دِينَ لِمَنْ لا وَرَعَ لَهُ، وَلا إِيمَانَ لِمَنْ لا تَقِيَّةَ لَهُ، إِنَّ أَكْرَمَكُمْ عِنْدَ اللَّهِ أَعْمَلُكُمْ بِالتَّقِيَّةِ. فَقِيلَ لَهُ: يَا ابْنَ رَسُولِ اللَّهِ إِلَى مَتَى؟ قَالَ: إِلَى يَوْمِ الْوَقْتِ الْمَعْلُومِ، وَهُوَ يَوْمُ خُرُوجِ قَائِمِنَا أَهْلَ الْبَيْتِ، فَمَنْ تَرَكَ التَّقِيَّةَ قَبْلَ خُرُوجِ قَائِمِنَا فَلَيْسَ مِنَّا.”

“Imam Ali ibn Musa al-Ridha, peace be upon him, said: ‘There is no religion for the one who has no piety (wara’), and there is no faith for the one who has no strategic prudence (taqiyyah). Indeed, the most noble of you in the sight of God is the one who practises strategic prudence (taqiyyah) the most.’

It was said to him: ‘O Son of the Messenger of God, until when?’

He replied: ‘Until the Day of the Known Time—and that is the day of the rising of our Qa’im from the Ahl al-Bayt. So whoever abandons strategic prudence (taqiyyah) before the rising of our Qa’im is not from us.’”

— Shaykh al-Saduq, Kamal al-Din wa Tamam al-Ni’mah, Vol. 2, Page 371, Hadith 5

— Al-Hurr al-Amili, Wasa’il al-Shia, Vol. 16, Page 211, Hadith 21382

Husayn ibn Ruh understood this.

The time for open declaration had not yet come.

Until the Mahdi rises, the mission must be preserved—even at the cost of public dignity.

Historical Evidence II: The Discipline of Silence

The extent of Husayn ibn Ruh’s discipline—and his intolerance for emotional recklessness—is further illustrated by the incident of the servant.

The Deputy had a servant who had served him for a considerable period.

On one occasion—likely provoked during an argument—this servant cursed Muawiyah.

Now, in a private gathering of the Shia, such an expression might be considered a statement of loyalty to the Ahl al-Bayt.

But Husayn ibn Ruh was not operating in a private gathering.

He was maintaining a delicate cover within the orbit of the Abbasid court—a court that, for all its conflicts with the Umayyads, still considered public cursing of the early Caliphs to be politically dangerous and a clear marker of Shia identity.

The servant’s outburst was a breach of operational security.

The Deputy dismissed him immediately.

Despite the servant’s pleading—and the intercession of prominent figures who begged Husayn ibn Ruh to forgive him—the Deputy remained adamant:

فَطَرَدَهُ عَنْهُ وَ عَزَلَهُ عَنْ خِدْمَتِهِ، فَشَفَعَ فِيهِ قَوْمٌ وَ أَلَحُّوا عَلَيْهِ، فَقَالَ: لَا يَعُودُ إِلَيَّ أَبَداً، فَإِنِّي أَخَافُ عَلَى نَفْسِي مِثْلَ هَذَا

“He expelled him and removed him from his service. A group of people interceded for him and pleaded with him to take him back, but he replied: ‘He shall never return to me. For I fear for my own safety—and the safety of the mission—from the likes of this man.’”

— Shaykh al-Tusi, Kitab al-Ghaybah, Section on the Stories of Husayn ibn Ruh

Let us be absolutely clear:

Husayn ibn Ruh was not defending Muawiyah.

He was defending the Mission.

He understood that a man who cannot control his tongue in minor matters lacks the discipline to protect the Imam in major ones.

The servant had prioritised his emotional release—the satisfaction of cursing—over the strategic security of the entire network.

The Lion’s Den has no room for emotional outbursts.

The School of Patience

The discipline we have witnessed in these two incidents — the verbal manoeuvre in the court and the dismissal of the servant — embodies what the martyred Secretary-General of Hizbullah, Sayyed Hassan Nasrallah, called the 'School of Patience' (Madrasat al-Sabr).

He argued that true power is not merely the ability to strike, but the ability to control when to strike.

In his analysis of the psychology of resistance, he emphasised that the restraint required to hold fire until the strategic moment is often more difficult—and more courageous—than the act of firing itself:

إِنَّ الْمُقَاوَمَةَ الَّتِي تَمْلِكُ السِّلَاحَ وَتَمْلِكُ الْقُدْرَةَ، وَلَكِنَّهَا تَمْلِكُ أَيْضاً الْعَقْلَ وَالْحِكْمَةَ وَالْبَصِيرَةَ، وَتَعْرِفُ مَتَى تُطْلِقُ النَّارَ وَمَتَى تَمْسِكُ

“The Resistance that possesses weapons and power, but also possesses intellect, wisdom, and insight, and knows when to open fire and when to hold it—that is the true Resistance.”

— Sayyed Hassan Nasrallah, Speech Commemorating the Martyred Leaders, February 16, 2011

Husayn ibn Ruh embodied this ultimate discipline.

He lived in the court of the tyrant, yet he possessed the wisdom to hold fire.

Lesson for the Present: Integration vs. Assimilation

The life of the Third Deputy offers a critical model for Muslims living in the West—or under any secular system—today.

Our communities often oscillate between two failed strategies:

Isolation — the Ghetto Mentality.

We retreat into our enclaves, refusing to engage with the broader society, convincing ourselves that purity requires separation.

We protect our faith, perhaps, but we lose all influence.

We produce generations who are religiously literate but professionally invisible, unable to shape the systems that govern their lives.

Assimilation — Melting into the System.

We enter the institutions of power, but we leave our principles at the door.

We become indistinguishable from those around us.

We gain position but lose purpose.

We are digested by the very system we once hoped to transform.

Husayn ibn Ruh represents the third, superior path: Strategic Presence.

He demonstrates that a believer can ascend to the highest levels of professional and social status—becoming a “Nawbakhti” of their time in medicine, engineering, law, politics, or academia—without compromising their core values.

By becoming the most indispensable professional in the room, the believer gains the power to protect the Truth and serve the community in ways the isolationist never can.

Clarification: Presence, Not Subversion

We must be careful with our terminology.

When we speak of entering the system, we do not mean the “infiltration” of a saboteur who enters a house to destroy it.

We mean the presence of the Salt in the Meal.

Consider: the salt enters the food completely.

It is not separate from it; it dissolves into every fibre of the dish.

Yet it does not become the food. It retains its essence.

And in doing so, it transforms the flavour of everything it touches.

Husayn ibn Ruh was the salt in the Abbasid court.

He was not there to destroy the administration.

He was not a spy planting bombs.

He was there to ensure that within that administration, justice had a witness, the truth had a guardian, and the believers had a shield.

The Nawbakhtis served the state in astronomy, philosophy, and administration.

They did not sabotage the state.

But wherever they were present, the Shia were protected.

Wherever they had influence, the community had breathing room.

This is Strategic Presence: to be so competent, so essential, so respected that your very position becomes a fortress for those who cannot protect themselves.

Call to Clarity: Agent or Asset?

This forces a difficult question upon each of us.

When we enter our workplaces, our universities, or the political sphere—what is our function?

Are you there simply to build a career?

To accumulate credentials and comfort?

Or are you there to establish a Strategic Presence—utilising your competence and status to protect the vulnerable and uphold the Truth?

Have you entered the system to influence it?

Or has the system assimilated you?

The Third Deputy walked into the Lion’s Den every day.

He sat among those who would have killed the Imam if they found him.

He smiled at men whose ideology he despised.

He held his tongue when every fibre of his being wanted to speak.

And he did it all—for decades—without ever losing himself.

The question is: can we do the same?

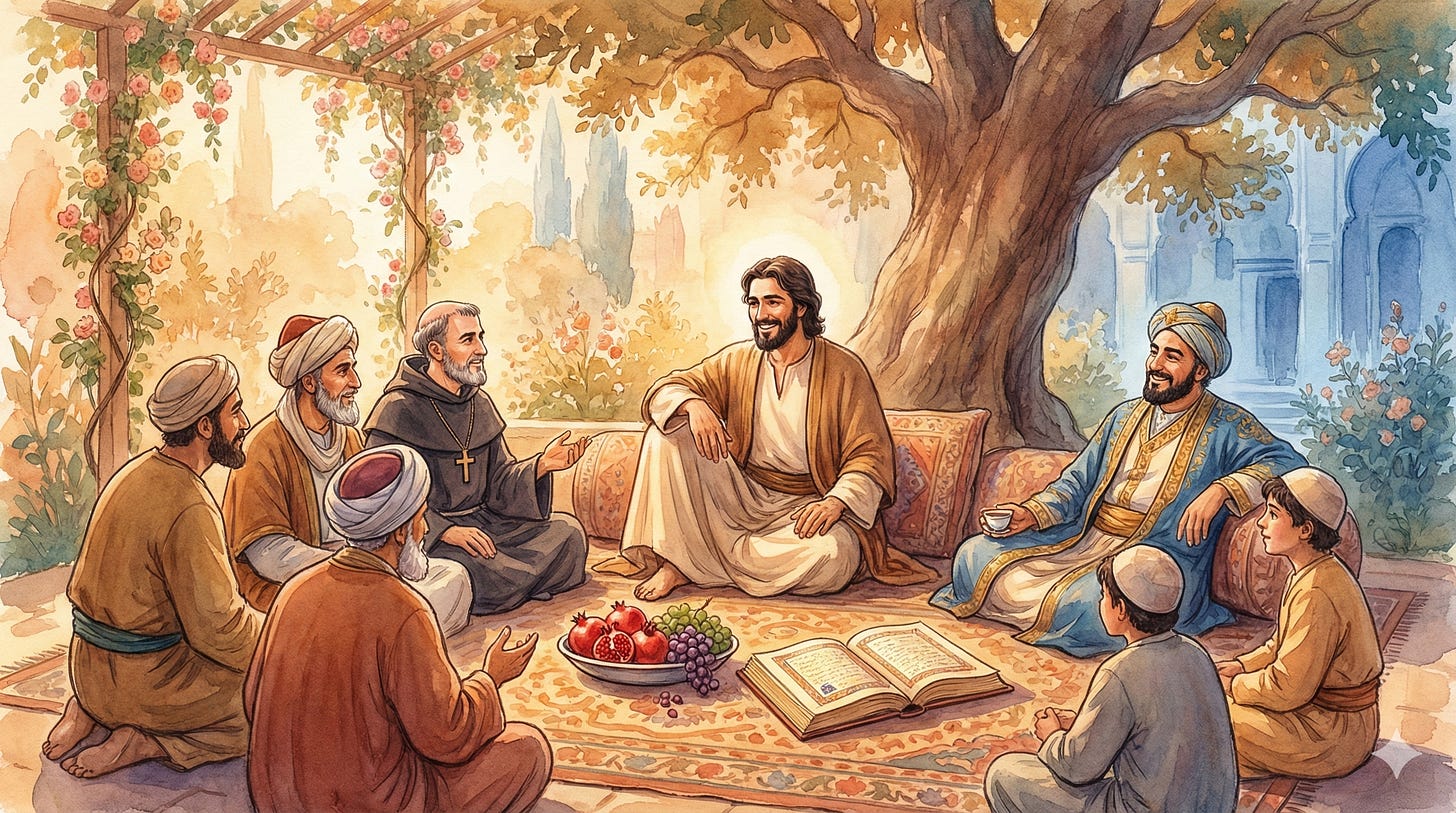

The Theology of Coexistence: Social Magnetism

The Personality: The Man Everyone Loved

If the first attribute of Husayn ibn Ruh was his political discipline, the second was his profound social intelligence.

There exists a dangerous stereotype in some religious circles that piety equates to isolation—that to be close to God, one must be distant from people, or that the “true believer” must be abrasive, stern, and constantly in a state of conflict with those who differ from him.

Husayn ibn Ruh dismantled this stereotype entirely.

He was the most accessible, the most social, and the most beloved of the Deputies.

He did not survive in the Abbasid court merely because he was clever; he survived because he possessed a character that disarmed his enemies.

He operated on the principle that the Truth is beautiful—and therefore, the bearer of Truth must not be repulsive.

Concept Clarification: Mudarat vs. Mudahanah

To understand his method, we must distinguish between two concepts that are often confused: Mudarat (Courtesy) and Mudahanah (Compromise).

Critics often accuse those who engage with society of “watering down” the religion.

They confuse diplomacy with hypocrisy.

Shaheed Murtadha Mutahhari, provides a surgical distinction between the two:

Mudahanah is a vice.

It means to flatter, to lie, or to sacrifice the Truth to gain worldly favour or avoid trouble.

It is the tactic of the hypocrite.

Mudarat is a virtue.

It means to treat people with kindness, to tolerate their ignorance, and to manage relationships with gentleness—in order to guide them or protect the community.

It is the tactic of the Prophet.

مُدارا غیر از مُداهنه است. مُداهنه یعنی رو دربایستی داشتن، یعنی حق را فدای مصلحت شخصی کردن... اما مُدارا یعنی نرمش نشان دادن برای پیشبرد حق. پیغمبر اکرم (ص) اهل مُدارا بود اما اهل مُداهنه نبود.

“Mudarat is different from Mudahanah. Mudahanah means to compromise out of shyness or fear, to sacrifice the Truth for personal expediency... But Mudarat means showing gentleness to advance the Truth. The Holy Prophet (peace be upon him and his family) was a man of Mudarat, but he was never a man of Mudahanah.”

— Shaheed Murtadha Mutahhari, Jazebeh va Dafe’eh-ye Ali (Polarisation around the Character of Imam Ali), Section: The Force of Attraction

Husayn ibn Ruh practised Mudarat.

He was kind to the Abbasid officials.

He visited them when they were ill.

He attended their gatherings.

He enquired after their families.

But he never sold the Imam.

He never compromised the Wilayah.

He used his good manners as a vehicle for the Truth, not a substitute for it.

The Prophetic Mandate

This social magnetism was not a personal quirk; it was a religious obligation.

The Holy Prophet, peace and blessings be upon him and his family, placed Mudarat on the same level as the obligatory prayers:

أَمَرَنِي رَبِّي بِمُدَارَاةِ النَّاسِ كَمَا أَمَرَنِي بِأَدَاءِ الْفَرَائِضِ

“My Lord commanded me to practise Mudarat (courtesy) with the people, just as He commanded me to perform the obligatory duties (Fara’id).”

— Al-Kulayni, Al-Kafi, Vol. 2, Page 117, Kitab al-Iman wa al-Kufr (Book of Faith and Disbelief), Chapter on Mudarat, Hadith 4

Pause and absorb the weight of this statement.

Mudarat is not “extra credit.”

It is not a recommendation for the spiritually advanced.

It is placed by God Himself on the same plane as prayers (salah), fasting (sawm) and charity, poor-due, alms (zakat).

If a believer performs his prayers but repels people with his harshness, he has fulfilled one half of the Prophet’s command and betrayed the other.

The Standard of Imam Ali

This principle was articulated most beautifully by the Commander of the Faithful, Imam Ali ibn Abi Talib, in a statement that serves as the measure of a believer’s social existence:

خَالِطُوا النَّاسَ مُخَالَطَةً إِنْ مِتُّمْ مَعَهَا بَكَوْا عَلَيْكُمْ، وَإِنْ عِشْتُمْ حَنُّوا إِلَيْكُمْ

“Associate with people in such a manner that if you die, they weep over you—and if you live, they crave your company.”

— Nahj al-Balaghah, Hikmah #10

This is the standard.

Not merely to be tolerated.

Not merely to survive among the people.

But to live in such a way that your absence creates a void—that those who knew you, even those who disagreed with you, feel the loss of your presence as a wound.

This is exactly how Husayn ibn Ruh lived.

And as we shall see, this is how the inheritors of his methodology have lived in our own time.

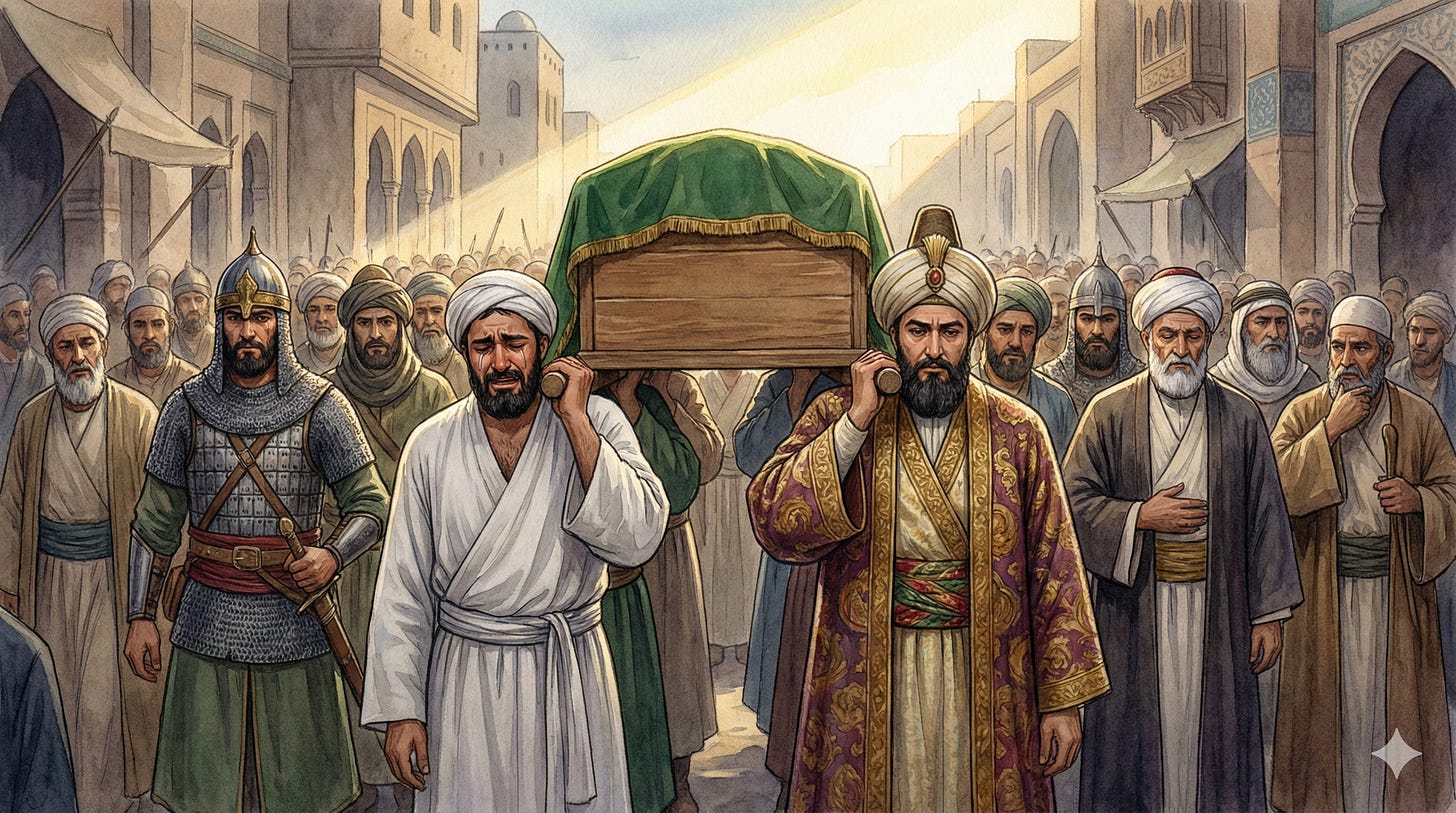

Historical Evidence: The Funeral of Unity

The ultimate proof of Husayn ibn Ruh’s success in this “Theology of Coexistence” was witnessed on the day of his death.

When he passed away in the year 326 AH, his funeral was not a clandestine affair conducted in the shadows, attended only by a handful of trusted Shia.

It was a state event.

The historical records indicate that the procession was attended not only by the weeping Shia who had lost their father figure, but also by the highest officials of the Abbasid state, the military commanders, and the Sunni judges:

وَلَمَّا تُوُفِّيَ رَضِيَ اللَّهُ عَنْهُ، صَلَّى عَلَيْهِ أَبُو طَالِبٍ الْكَاتِبُ مِنْ أَعْيَانِ الدَّوْلَةِ، وَشَيَّعَهُ خَلْقٌ كَثِيرٌ مِنَ الشِّيعَةِ وَالسُّنَّةِ وَأَرْبَابِ الدَّوْلَةِ.

“When he passed away, may God be pleased with him, Abu Talib the Scribe—one of the notables of the [Abbasid] State—prayed over him. He was escorted to his grave by a multitude of people, including the Shia, the Sunnis, and the lords of the State.”

— Sayyed Muhsin al-Amin, A’yan al-Shia, Vol. 6, Biography of Husayn ibn Ruh. Corroborated by Al-Dhahabi, Siyar A’lam al-Nubala.

This scene is profound.

The man who was the secret head of the Resistance—the man who held the keys to the Imamate, who had deflected the sword with the wand of words, who had protected the Hidden Imam for over two decades—was carried to his grave on the shoulders of the very system that sought to destroy his Master.

He had built such a reservoir of respect—through his intellect (aql) and his manners (akhlaq)—that even his ideological opponents felt compelled to honour him.

He did not live in a ghetto.

He lived in the hearts of the people, regardless of their sect.

The Modern Mirrors: Resistance with Compassion

The methodology of Husayn ibn Ruh did not die with him.

It has been inherited, generation after generation, by those who understood that strength without beauty is incomplete.

In our own era, we have witnessed this standard embodied by luminaries whose lives—and whose funerals—echoed that of the Third Deputy.

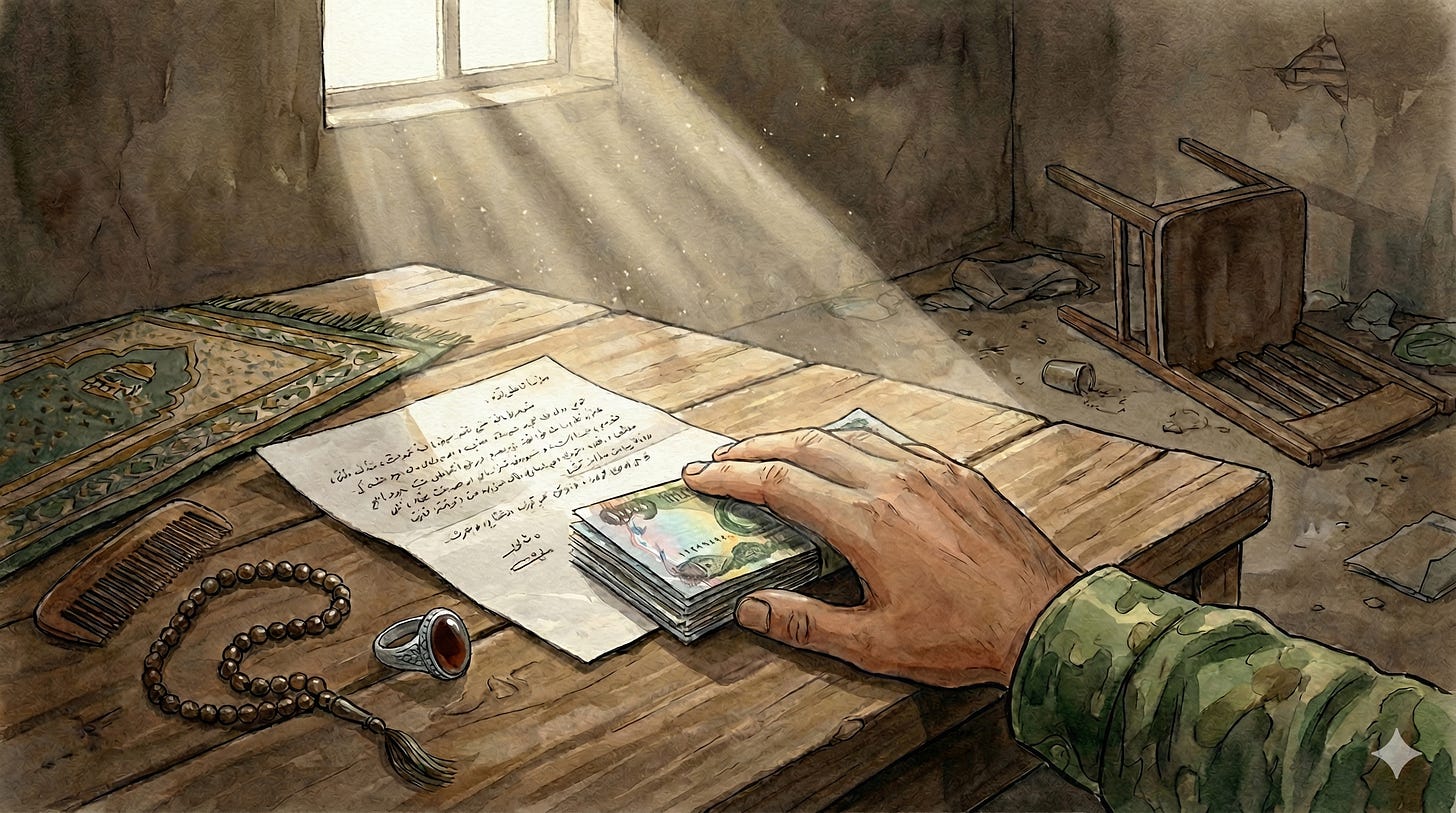

The General of Hearts

When Hajj Qassem Soleimani was martyred in January 2020, the world witnessed something the Western media could not comprehend.

Millions filled the streets—not merely in Iran, but in Iraq, in Lebanon, in Syria.

The funeral processions stretched for miles.

People wept as though they had lost a father.

The enemies called him a “terrorist.”

But those who knew him—Sunni tribal leaders in Iraq, Christian commanders in Syria, Kurdish fighters in the mountains—spoke of a man who treated every person with dignity.

One incident captures this character precisely.

During the operations to liberate Amerli—or in the outskirts of Mosul, the sources vary on the exact location—Hajj Qassem and his forces took shelter in the empty home of a Sunni family who had fled the fighting.

Before leaving, he wrote a letter in his own hand and left it with a sum of money:

“العائلة العزيزة والمحترمة... أنا أخوكم الصغير قاسم سليماني. لقد اضطررت لاستخدام منزلكم للصلاة والراحة. لقد صليت ركعتين لكم وطلبت من الله عاقبة الخير لكم... لقد وضعت مبلغاً من المال تعويضاً عن أي شيء استخدمناه... إذا كان المبلغ قليلاً فأرجو أن تسامحوني وتتصلوا بي على هذا الرقم إذا كان لديكم أي حق آخر.”

“To the dear and respected family... I am your younger brother, Qassem Soleimani. I was compelled to use your house for prayer and rest. I prayed two units of prayer for you and asked God for a good outcome for you... I have left a sum of money as compensation for anything we used... If the amount is insufficient, I hope you forgive me—and please contact me at this number if you have any further claim (haqq).”

— Handwritten letter of Hajj Qassem Soleimani, documented by Al-Mayadeen and Fars News Agency

This is the man the world called a monster.

A man who, in the chaos of war, paused to pray for a Sunni family he had never met—and left his personal phone number in case he owed them anything more.

This is Mudarat.

This is the methodology of Husayn ibn Ruh, alive in the twenty-first century.

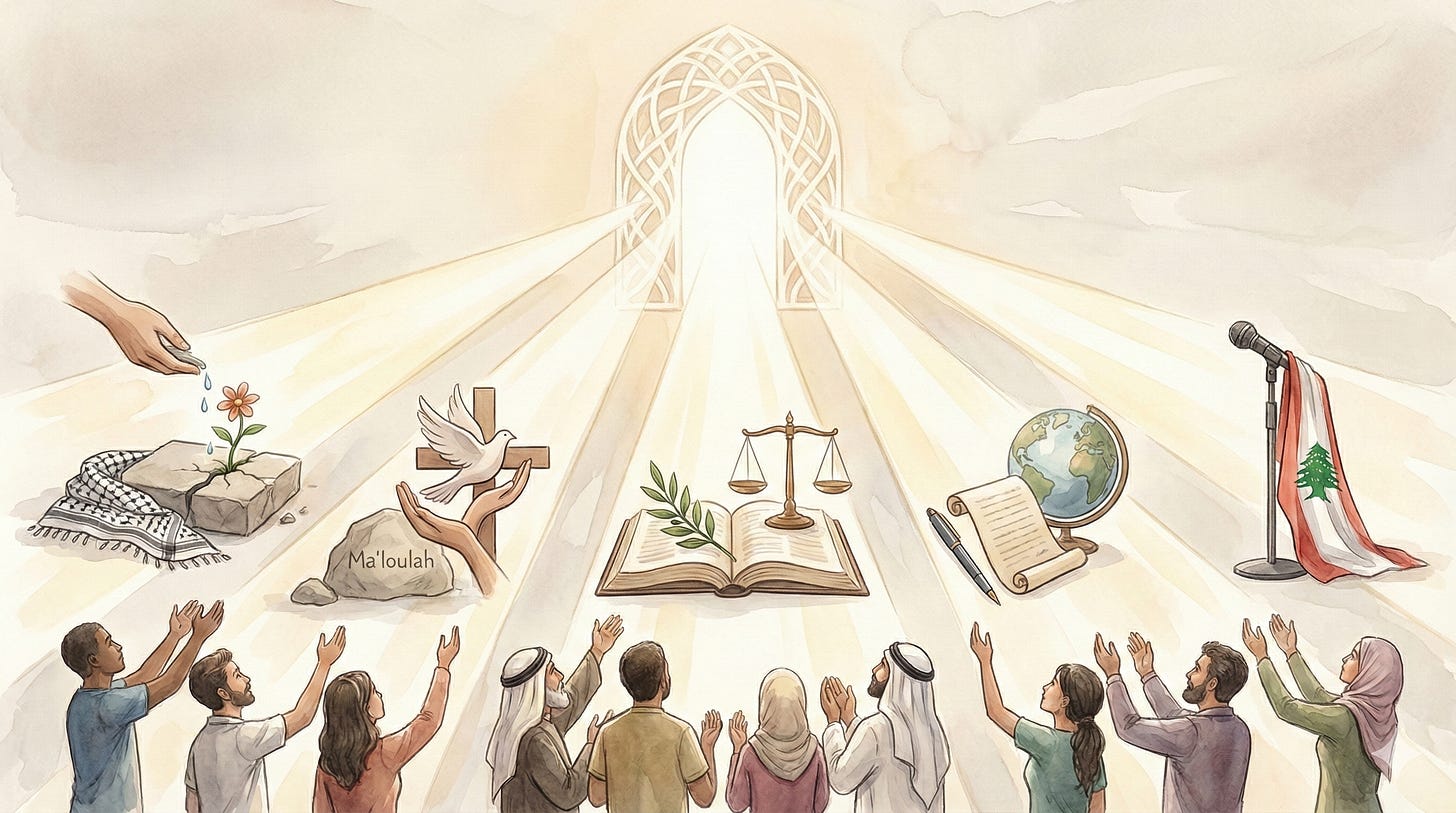

The Protectors of the Cross

And then there is the testimony of Ma’loula.

In 2013, the ancient Christian town of Ma’loula in Syria—one of the last places on earth where Aramaic, the language of Prophet Jesus, is still spoken—was overrun by Al-Nusra Front.

The takfiri militants kidnapped the nuns of the Mar Takla Convent and desecrated the churches.

It was Hizbullah—the “Party of God,” the Shia resistance—who came to liberate them.

When the town was freed and the nuns released, Mother Pelagia Sayyaf, the Superior of the Convent, gave her testimony:

“The way they treated us was full of respect... They did not force us to remove our crosses... They defended the church as if it were a mosque.”

— Mother Pelagia Sayyaf, reported by Reuters and BBC, March 2014.

Shia soldiers, followers of the Ahl al-Bayt, defending Christian nuns and ancient churches from those who claimed to act in the name of Islam.

This is the mirror of the Beautiful.

This is resistance with compassion.

The Architect of Dialogue

This lineage of “Strategic Presence” was masterfully articulated in the mid-twentieth century by the vanished Imam, Musa al-Sadr.

When he arrived in Lebanon in 1959, the Shia were known as the Mahroumin—the Dispossessed.

They were marginalised, impoverished, and invisible.

He could have chosen the path of isolation.

He could have built walls to protect the “purity” of his community from the secular and Christian influences of Beirut.

Instead, he chose the path of Husayn ibn Ruh.

He entered the churches.

He sat with French aristocrats and village farmers.

He debated Marxists in coffee houses and drank tea with Maronite Patriarchs.

On February 19, 1975, he did the unthinkable.

He stood at the altar of the St. Louis Capuchin Church and delivered a Lenten sermon to a Christian congregation.

He did not compromise his monotheism, but he appealed to their shared humanity:

“اجتمعنا من أجل الإنسان، الذي كانت من أجله الأديان... والإنسان في لبنان ممتحن في إنسانيته.”

“We have gathered for the sake of Man, for whom religions came to exist... And Man in Lebanon is being tested in his humanity.”

— Imam Musa al-Sadr, Sermon at the Capuchin Church, recorded in Kalimat al-Imam al-Sadr (Words of Imam Sadr), Vol. 1.

His magnetism was so potent that he ceased to be a “Shia cleric” and became a national treasure.

A Christian woman in Tyre, witnessing his relentless service to the poor of all sects, famously remarked:

“If this man had been present when Christ was alive, I would have followed him.”

— Documented in Fouad Ajami, The Vanished Imam, Pages 46-48.

He taught us that the “Weapon of the Stance” (Silah al-Mawqif) is stronger than the weapon of the gun.

He proved that you can be a revolutionary cleric and still be the most beloved man in a diverse state.

The Father of Orphans

And we saw this same spirit in the late Ayatullah Sayyed Muhammad Husayn Fadhlullah.

While others focused on building structures of stone, he focused on building the human being.

He rejected the “Ghetto” mentality that views the “Other” as a threat.

He famously declared:

“ليس هناك ‘آخر’ يسقط أمامي. الآخر هو إنسان أختلف معه في الفكر، ولكني ألتقي معه في الإنسانية.”

“There is no ‘Other’ that falls before me. The Other is a human being with whom I differ in thought, but with whom I meet in humanity.”

— Ayatullah Fadhlullah, Hiwarat fi al-Fikr wa al-Siyasah (Dialogues in Thought and Politics), Interview Archives.

He translated this theology into dignity.

When he established the Al-Mabarrat orphanages, he insisted they be state-of-the-art institutions—often better than the private schools of the elite.

When asked why, he replied:

“لا أريد لليتيم أن يشعر بذل اليتيم. أريده أن يشعر أنه في بيته، مكرمًا عزيزًا.”

“I do not want the orphan to feel the humiliation of orphanhood. I want him to feel he is in his own home—honoured and dignified.”

— Documented in the history of Jam’iyyat al-Mabarrat al-Khayriyya.

This is the legacy of the Third Deputy: to be so beneficial to society, so radiant in character, that your very existence becomes a proof for your faith.

The Martyred Secretary-General

But perhaps the clearest embodiment of this methodology in our time was the martyred Secretary-General of Hizbullah, Sayyed Hassan Nasrallah.

His character was such that it transcended the boundaries of his own sect and even his own geography.

He was a “Magnet” in the truest sense—drawing respect from the most unexpected quarters.

The Testimony of the Intellectual

Even those from vastly different backgrounds felt the pull of his intellect and integrity. Dr. Norman Finkelstein—the prominent Jewish-American political scientist, son of Holocaust survivors, a man with no religious or political alignment with the Resistance—was asked about the leader of Hezbollah.

He did not describe a sectarian warlord. He stated:

“He [Nasrallah] is the smartest, most capable political leader in the world today. I don’t mean in the Middle East—I mean in the world... He is the only political leader in the world from whom you learn something. He is a teacher.”

— Dr. Norman Finkelstein, Interview with OTV (Lebanon), January 2008

The Testimony of the Diplomat

This respect extended to the highest corridors of global power.

Kofi Annan, the former United Nations Secretary-General, negotiated directly with Sayyed Hassan during the height of the 2006 conflict.

Despite representing an “International Community” that often sided against the Resistance, Annan had to acknowledge the man’s unique stature.

Unlike many politicians who say one thing and do another, Annan observed:

“I found him to be calm, reflective... He is a man who is very much in control... and a man of his word.”

— Kofi Annan, Press Briefing, Beirut, August 29, 2006. Also referenced in his memoir Interventions: A Life in War and Peace.

The Testimony of the Enemy

But perhaps the most stunning proof of his truthfulness (sidq)—a key component of Mudarat—came from the enemy itself.

During the 2006 July War, while Israeli bombs were falling on Beirut, the Israeli Dahaf Institute conducted a poll.

They asked the Israeli public a simple question:

Who do you trust more—your own Prime Minister, or the leader of Hizbullah?

The result was a humiliation for the Zionist state:

“80% of Israelis believed Nasrallah’s speeches were more truthful than the statements of their own Prime Minister, Ehud Olmert.”

— Yedioth Ahronoth (Israeli Daily Newspaper), August 2006. Published under the headline: “Nasrallah More Credible Than Olmert.”

Pause and absorb this.

The enemy—the very people his rockets were aimed at—trusted him more than they trusted their own government.

Why?

Because even the enemy knew: a student of the School of Ahl al-Bayt does not lie.

His “Social Magnetism” was not a performance.

It was not a public relations strategy.

It was built on the bedrock of absolute integrity—the same integrity that allowed Husayn ibn Ruh to earn the respect of the Abbasid court while never betraying the Imam.

When Sayyed Hassan was martyred, his funeral—like that of the Third Deputy over a thousand years before—was not a sectarian affair.

Christians wept for him.

Druze leaders honoured him.

Even those who disagreed with his politics acknowledged that Lebanon had lost a man of rare calibre.

If you die, they weep over you.

They wept.

The Theological Root: The Mirror of the Beautiful

Why does this matter?

Because the believer is the mirror of God.

In the school of mysticism (Irfan)—and indeed in the Quran itself—we recognise that God possesses attributes of both Majesty (Jalal) and Beauty (Jamal).

He is Al-Qahhar (The Subduer), but He is also Al-Latif (The Subtle), Al-Wadud (The Loving), and Al-Jamil (The Beautiful).

The Prophet, peace and blessings be upon him and his family, said:

إِنَّ اللَّهَ جَمِيلٌ يُحِبُّ الْجَمَالَ

“Indeed, God is Beautiful and He loves beauty.”

— Sahih Muslim (Muslim ibn al-Hajjaj al-Naysaburi), Kitab al-Iman, Hadith 91

And in the Shia collections, the Commander of the Faithful, Imam Ali ibn Abi Talib, transmits the same teaching with an important addition:

إِنَّ اللَّهَ جَمِيلٌ يُحِبُّ الْجَمَالَ، وَيُحِبُّ أَنْ يُرَى أَثَرُ نِعْمَتِهِ عَلَى عَبْدِهِ

“Indeed, God is Beautiful and loves beauty—and He loves that the effect of His blessing be seen upon His servant.”

— Al-Kulayni, Al-Kafi, Vol. 6, Page 438-439, Kitab al-Zi wa al-Tajammul (Book of Dress and Adornment), Hadith is attributed to Imam Ali

Notice the addition:

“He loves that the effect of His blessing be seen upon His servant.”

The believer is not meant to hide the beauty of faith.

He is meant to manifest it—to make it visible in his character, his dealings, his very presence.

Imam Ja’far al-Sadiq reinforces this principle:

إِنَّ اللَّهَ عَزَّ وَجَلَّ يُحِبُّ الْجَمَالَ وَالتَّجَمُّلَ، وَيُبْغِضُ الْبُؤْسَ وَالتَّبَاؤُسَ

“Indeed, God, Mighty and Majestic, loves beauty and beautification—and He dislikes misery and the pretence of misery.”

— Imam Ja’far al-Sadiq, in Al-Kulayni, Al-Kafi, Vol. 6, Page 438, Kitab al-Zi wa al-Tajammul, Hadith 1.

God dislikes al-taba’us—the affectation of wretchedness, the performance of misery, the assumption that piety must look grim.

If the representative of the Faith is purely abrasive, socially repellent, or offensive in his dealings, he presents a distorted image of the Divine.

He reflects only might and power (jalal) while obscuring beauty (jamal).

He blocks the path to God with his own ego.

You cannot invite people to the “Beautiful Path” with ugly behaviour.

The medium must match the message.

Concept Clarification: The True Meaning of Bara’ah

Before we conclude with the lesson for today, we must define a term that is frequently misunderstood: Bara’ah (Dissociation).

You will often hear pious youth say:

“I cannot interact with these people; I must practise Bara’ah.”

They interpret this concept as a license for rudeness, social isolation, or total disconnection from anyone who does not share their beliefs.

This is a distortion.

Bara’ah does not mean “Social Boycott” of the innocent.

It means “Political and Moral Dissociation” from the oppressors and the enemies of God.

It is a stance of the heart and the principles against injustice—not a stance of the ego against neighbours or colleagues.

The Holy Quran explicitly draws this boundary in Surah Al-Mumtahanah.

Immediately after commanding Bara’ah from the enemies of God, the verse that follows clarifies the status of peaceful non-believers:

لَّا يَنْهَاكُمُ اللَّهُ عَنِ الَّذِينَ لَمْ يُقَاتِلُوكُمْ فِي الدِّينِ وَلَمْ يُخْرِجُوكُم مِّن دِيَارِكُمْ أَن تَبَرُّوهُمْ وَتُقْسِطُوا إِلَيْهِمْ ۚ إِنَّ اللَّهَ يُحِبُّ الْمُقْسِطِينَ

“God does not forbid you, regarding those who have not fought you in religion nor driven you out of your homes, from dealing kindly (tabarruhum) with them and acting justly toward them. Indeed, God loves those who act justly.”

— Quran, Surah Al-Mumtahanah (the Chapter of the Woman Examined) #60, Verse 8

The Exegesis of Coexistence

Allamah Tabatabai, in his monumental commentary Al-Mizan, explains the precise relationship between Bara’ah and human interaction:

قَوْلُهُ تَعَالَى: (لَا يَنْهَاكُمُ اللَّهُ عَنِ الَّذِينَ لَمْ يُقَاتِلُوكُمْ...) الآيَةُ بَيَانٌ لِمَنْ لَا تَجِبُ الْبَرَاءَةُ مِنْهُمْ مِنَ الْكُفَّارِ... وَالْمَعْنَى: لَا يَنْهَاكُمُ اللَّهُ عَنْ أَنْ تَبَرُّوا هَؤُلَاءِ وَتُقْسِطُوا إِلَيْهِمْ، فَإِنَّ إِيجَابَ الْبَرَاءَةِ مِنْهُمْ لَا يُوجِبُ حُرْمَةَ الْإِحْسَانِ إِلَيْهِمْ وَالْعَدْلِ فِيهِمْ.

“The Word of the Exalted... is a clarification regarding those disbelievers from whom Dissociation (Bara’ah) is NOT obligatory... The meaning is: God does not forbid you from showing kindness (Birr) to these people and acting justly toward them. For indeed, the obligation of Dissociation (Bara’ah) from [their false beliefs or hostile leaders] does not necessitate the prohibition of doing good (Ihsan) to them or treating them with Justice.”

— Allamah Tabatabai, Al-Mizan fi Tafsir al-Quran, Vol. 19, Commentary on Surah Al-Mumtahanah (the Chapter of the Woman Examined) #60, Verse 8

The obligation of Bara’ah does not prohibit Ihsan.

You can dissociate from falsehood while still doing good to those who hold it.

Ayatullah Jawadi-Amoli, in his thematic exegesis of Quranic ethics, takes this principle further.

He argues that justice is not a privilege reserved for Muslims—it is a universal human right:

«عدل و قسط، حقِ عمومی انسانهاست، نه حقِ مخصوص مؤمنان. حتی کافر نیز تا زمانی که دست به شمشیر نبرده است، حق دارد که با او به عدالت رفتار شود. آیه شریفه سوره ممتحنه گواه بر این است که رابطه انسانی با کافرِ غیرحربی، باید بر اساس “برّ” (نیکی) و “قسط” (عدالت) باشد.»

“Justice and Equity (Qist) are the general rights of human beings, not the specific rights of believers. Even the disbeliever, as long as he has not drawn the sword, has the right to be treated with justice. The noble verse of Surah Al-Mumtahanah serves as evidence that the human relationship with the non-hostile disbeliever must be based on Birr (Kindness) and Qist (Justice).”

— Ayatullah Abdullah Jawadi-Amoli, Mabadi-ye Akhlaq dar Quran (Foundations of Ethics in the Quran), Vol. 10 of the Thematic Exegesis series, Chapter: Justice with Non-Muslims

This is not liberal relativism.

This is Quranic ethics as explained by the most rigorous scholars of our tradition.

The Linguistic Beauty

Notice the word God uses: Tabarruhum—”be righteous to them,” “deal kindly with them.”

It comes from Birr—the same root used for kindness to parents (Birr al-Walidayn), the highest form of interpersonal duty in Islam.

Here is the linguistic beauty:

You can have Bara’ah (dissociation) from a person’s false beliefs or corrupt leaders—while simultaneously having Birr (kindness) toward them as human beings.

The two are not contradictory.

They operate on different planes.

Bara’ah is in the heart and in the principles.

Birr is in the conduct and in the dealings.

The Scholar’s Definition

Shaheed Murtadha Mutahhari, in his masterpiece Jazebeh va Dafe’eh-ye Ali (Polarisation around the Character of Imam Ali), explains that Bara’ah is a surgical tool, not a blunt instrument.

It is directed at traits—hypocrisy, injustice, oppression—not indiscriminately at people:

«دفع علی (ع) مانند جذبش سخت نیرومند بود... اما دفع او شامل چه کسانی بود؟ شامل منافقان، شامل غارتگران بیت المال، و شامل کسانی که دین را دکان کرده بودند. او با اینها دشمن بود، نه با مردم عوام و ناآگاه.»

“The Repulsion (Dafe’eh / Bara’ah) of Ali was as powerful as his Attraction... But whom did his Repulsion include? It included the hypocrites, the looters of the public treasury, and those who made religion into a shop. He was an enemy to these—not to the common, unaware people.”

— Shaheed Murtadha Mutahhari, Jazebeh va Dafe’eh-ye Ali (Polarisation around the Character of Imam Ali), Introduction

Imam Ali’s Bara’ah was directed at the corrupt elite, not at ordinary people struggling to find their way.

This is precisely how Husayn ibn Ruh operated.

When he engaged with the Abbasid court, he maintained Bara’ah in his heart—he hated their tyranny and rejected their illegitimate claim to leadership.

But he practised Mudarat (Courtesy) in his behaviour.

He sat with them, conversed with them, earned their respect—while never abandoning his principles.

He did not confuse the sin with the sinner.

He did not mistake the system for every individual within it.

And neither should we.

Lesson for the Present: The Death of the Ghetto Mentality

This reality challenges a toxicity that has infected parts of our modern community: the Ghetto Mentality.

There is a tendency to believe that “Us vs. Them” is the default state of faith.

We treat isolation as piety.

We justify our disengagement from society—whether from a different sect, a different religion, or no religion at all—by claiming we are protecting our faith from contamination.

But Husayn ibn Ruh teaches us otherwise.

You can hold firm to the Truth while still being the kindest person in the room.

You can reject an ideology while still honouring the humanity of those who hold it.

The Mandate of Ayatullah Sistani

Ayatullah Sistani, the highest religious authority for millions of Shia Muslims worldwide, has issued clear directives on this matter—directives that are not mere suggestions, but juridical rulings (fatawa) that carry the weight of religious obligation.

First, he commands the believing youth to become contributors, not spectators:

عَلَى كُلِّ وَاحِدٍ مِنْكُمْ أَنْ يَسْعَى فِي اكْتِسَابِ مِهْنَةٍ... وَأَنْ يَكُونَ نَافِعاً لِنَفْسِهِ وَأَهْلِهِ وَمُجْتَمَعِهِ... فَإِنَّ اللَّهَ تَعَالَى يُحِبُّ الْمُحْتَرِفَ الْأَمِينَ وَيَكْرَهُ الْبَطَّالَ.

“It is incumbent upon every one of you to strive to acquire a profession... and to be beneficial to himself, his family, and his society... For indeed, God the Exalted loves the trustworthy professional and dislikes the idle person.”

— Ayatullah Sistani, Risalah ila al-Shabab al-Mu’min (Message to the Believing Youth), published on sistani.org

God loves the trustworthy professional.

God dislikes the idle person.

This is not cultural advice; this is theology.

The believer who retreats into isolation, who refuses to develop expertise, who contributes nothing to the society around him—this person is not pleasing God with his “purity.”

He is displeasing God with his idleness.

Second, Ayatullah Sistani addresses those living in non-Muslim countries with a ruling that reframes the very nature of citizenship and residency:

إِذَا أَعْطَى الْمُسْلِمُ لَهُمُ الْأَمَانَ... أَوْ دَخَلَ بِلَادَهُمْ بِأَمَانٍ مِنْهُمْ (كَالتَّأْشِيرَةِ)، حَرُمَ عَلَيْهِ الْغَدْرُ بِهِمْ وَالْخِيَانَةُ لَهُمْ، بِسَرِقَةٍ أَوْ غِشٍّ أَوْ نَحْوِهِمَا... فَإِنَّ الْأَمَانَةَ تُؤَدَّى إِلَى الْبَرِّ وَالْفَاجِرِ.

“If a Muslim grants them security... or enters their lands with security from them (such as a visa), it is forbidden (Haram) for him to betray them or deceive them—whether by stealing, cheating, or similar acts... For indeed, the trust (Amanah) must be returned to both the righteous and the corrupt.”

— Ayatullah Sistani, Al-Fiqh li al-Mughtaribin (A Code of Practice for Muslims in the West), Chapter: Legal Dealings in Non-Muslim Countries, Ruling #2

When you accepted that visa, when you took that citizenship oath, you entered into a covenant—an Aman.

And covenants, in Islamic law, are sacred.

To betray that trust—through dishonesty, through crime, through any form of deception—is not merely illegal; it is Haram.

The trust must be returned to “both the righteous and the corrupt.”

Even if the government is unjust, even if you disagree with their policies, the personal covenant you made when you entered their land remains binding.

This is Mudarat codified into law.

The Vision of Imam Khamenei

Imam Khamenei, the Leader of the Islamic Revolution, has similarly called upon Muslims—particularly the youth—to reject isolation and engage constructively with the world around them.

In his historic letter addressed directly to the youth of Europe and North America, he did not call for retreat.

He called for bridge-building:

”Although no one can individually fill the created gaps, each one of you can construct a bridge of thought and fairness over the gaps to illuminate yourself and your surrounding environment.”

— Imam Khamenei, To the Youth in Europe and North America, Official Letter, January 21, 2015 (khamenei.ir)

A bridge—not a wall.

Illumination—not isolation.

Each individual believer has a responsibility to construct something that connects, that allows understanding to pass across the divide.

And on the specific question of how Muslims should treat non-Muslims in their daily interactions, Imam Khamenei returns to the same Quranic verse we examined earlier—Surah Al-Mumtahanah—and affirms its universal application:

«اسلام به ما دستور داده است که با پیروان ادیان دیگر با انصاف و عدالت رفتار کنیم. این آیه شریفه: “لا یَنهاکُمُ اللهُ...” دستور میدهد که با کسانی که با شما سر جنگ ندارند، با نیکی و قسط رفتار کنید.»

“Islam has commanded us to treat the followers of other religions with fairness (Insaf) and justice (Adalah). This noble verse: ‘God does not forbid you...’ commands that you treat those who are not at war with you with kindness and equity.”

— Imam Khamenei, Statements during meeting with officials, published on khamenei.ir

This is not the voice of one scholar.

This is the unified position of the two most prominent authorities in the Shia world today—Ayatullah Sistani in Najaf and Imam Khamenei in Qom and Tehran.

Both command integration.

Both forbid the ghetto mentality.

Both point back to the same Quranic foundation and the same methodology embodied by Husayn ibn Ruh over a thousand years ago.

The Standard of the Imam

Ayatullah Sistani returns to the foundational teaching of Imam Ja’far al-Sadiq—the standard by which all social behaviour must be measured:

كُونُوا زَيْناً لَنَا وَ لَا تَكُونُوا شَيْناً عَلَيْنَا... قُولُوا لِلنَّاسِ حُسْناً وَ احْفَظُوا أَلْسِنَتَكُمْ

“Be an ornament for us, and do not be a disgrace for us... Speak to people with goodness, and guard your tongues.”

— Al-Saduq, Al-Amali, Session 62, Hadith 4 (Frequently referenced by Ayatullah Sistani in Al-Fiqh li al-Mughtaribin, Introduction)

An ornament beautifies whatever it is attached to.

A disgrace tarnishes it.

When people encounter you—at work, in the neighbourhood, at the university—do they see an ornament of the Ahl al-Bayt, or a disgrace upon their name?

Does your behaviour make them say,

“If this is what a follower of the Imam looks like, perhaps I should learn more”?

Or does it make them say,

“If this is Islam, I want nothing to do with it”?

Call to Clarity: The Magnet vs. The Wall

We must ask ourselves honestly:

When people interact with us, does our behaviour make them curious about the Imam we follow, about our Islam—or does it confirm their worst prejudices?

Do we draw hearts toward the Truth, or do we repel them before they can even hear the message?

Husayn ibn Ruh was a magnet.

He drew the hearts of the Abbasid court toward him, and in doing so, he created a safe space for the Truth to survive.

Are we magnets?

Or are we walls?

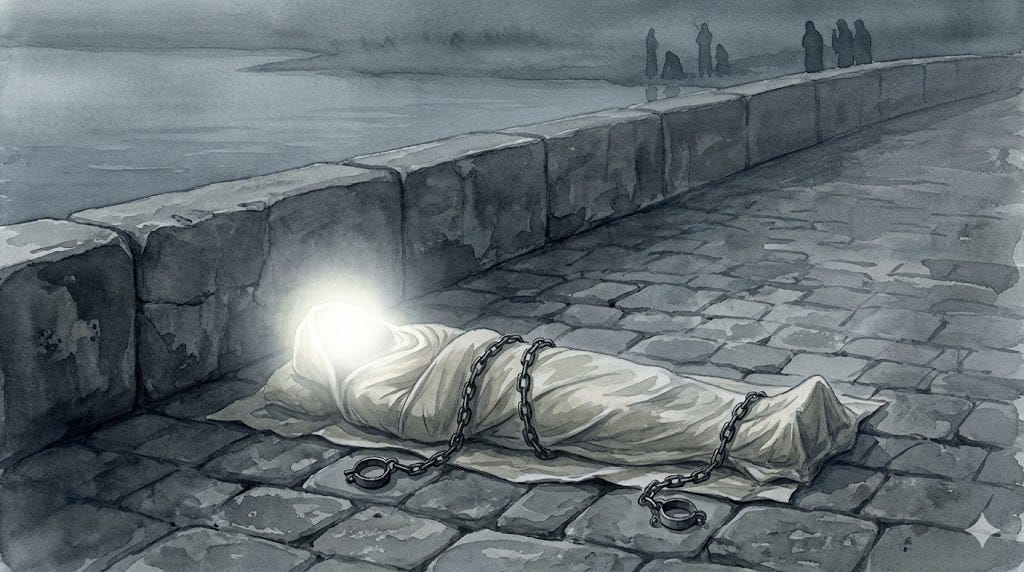

The Internal Cancer: The Betrayal of Shalmaghani

The Imprisonment: When the Cat Was Caged

Before we examine the traitor, we must understand what created the opportunity for his treachery.

Husayn ibn Ruh did not go to prison for “being a Shia.”

The Abbasids were more sophisticated than that.

They used a financial pretext for political persecution.

The Abbasid court was locked in a perpetual struggle between rival factions.

On one side stood the Banu Furat—led by the Vizier Abu al-Hasan ibn al-Furat—who were sympathetic to the Shia and provided them protection.

On the other stood the faction of Hamid ibn al-Abbas and his secretary Ali ibn Isa, who sought to dismantle the Shia network by cutting off its funds.

In 312 AH, the Pro-Shia Vizier fell from power and was executed.

The Anti-Shia faction seized control.

They launched a purge.

Their weapon was not the sword—it was the ledger.

They accused Husayn ibn Ruh of owing vast sums of money to the state, effectively framing the Khums funds of the believers as unpaid taxes or embezzled state wealth.

The historical record documents what followed:

وَلَمَّا قُبِضَ عَلَى ابْنِ الْفُرَاتِ وَنُكِبَ، طُولِبَ الشَّيْخُ أَبُو الْقَاسِمِ [الْحُسَيْنُ بْنُ رُوحٍ] بِالْأَمْوَالِ، وَاخْتَفَى. فَقُبِضَ عَلَى جَمَاعَةٍ مِنْ أَصْحَابِهِ... ثُمَّ ظَفَرُوا بِالشَّيْخِ أَبِي الْقَاسِمِ فَحُبِسَ فِي دَارِ الْمُقْتَدِرِ خَمْسَ سِنِينَ.

“When Ibn al-Furat was arrested and overthrown [in 312 AH], the Shaykh Abu al-Qasim [Husayn ibn Ruh] was pursued for funds [money demanded by the state], so he went into hiding. A group of his associates were arrested... Then they captured the Shaykh Abu al-Qasim, and he was imprisoned in the house of [the Caliph] Al-Muqtadir for five years.”

— Shaykh al-Tusi, Kitab al-Ghaybah, Section: Akhbar Husayn ibn Ruh

Husayn ibn Ruh initially went into hiding—a Ghaybah of his own—to evade arrest.

But the pressure on his family and associates became unbearable.

He was eventually detained in 312 AH.

The state demanded he pay an exorbitant ransom for his release—a sum that would have bankrupted the network and legitimised the extortion.

He refused.

Because he refused, he was moved from house arrest to harsher confinement.

For five years—from 312 AH to 317 AH—the Third Deputy languished in the dungeons of the Caliph.

And it was precisely during this vacuum of leadership—while the Cat was caged—that the Mouse began to play.

A man named Muhammad ibn Ali al-Shalmaghani saw his opportunity.

The Profile of the Traitor

We have seen how Husayn ibn Ruh dealt with the external enemy—the Abbasid State—through Mudarat (Courtesy).

He smiled at them, attended their gatherings, earned their respect.

Now, we must witness how he dealt with the internal enemy.

And this is the most terrifying lesson of all.

The greatest threat to the Third Deputy did not come from the Caliph’s palace.

It came from the mosque.

It came from a man named Muhammad ibn Ali al-Shalmaghani—also known as Ibn Abi al-Azaqir.

Who was Shalmaghani?

He was not a drunkard.

He was not a known sinner.

He was not an outsider who infiltrated the community.

He was the “Right Hand” of the Third Deputy.

He was a scholar of the highest calibre—a Faqih who had authored the influential book Kitab al-Taklif (the Book of Duties).

He was the intermediary between Husayn ibn Ruh and the agents of Baghdad.

The community revered him.

When people had complex theological questions, the Deputy would often refer them to Shalmaghani.

He was the “Celebrity Scholar” of his day.

The sources record his prominence:

كَانَ أَبُو جَعْفَرٍ ابْنُ أَبِي الْعَزَاقِرِ [الشَّلْمَغَانِيُّ] وَجِيهاً عِنْدَ بَنِي بِسْطَامَ... وَكَانَ النَّاسُ يَقْصِدُونَهُ فِي حَوَائِجِهِمْ لِمَكَانِهِ مِنَ الشَّيْخِ أَبِي الْقَاسِمِ [الْحُسَيْنِ بْنِ رُوحٍ]... وَكَانَ قَدْ صَنَّفَ كِتَابَ التَّكْلِيفِ.

“Abu Ja’far ibn Abi al-Azaqir [Al-Shalmaghani] was a prominent figure among the Banu Bistam... People would seek him out for their needs due to his close position to the Shaykh Abu al-Qasim [Husayn ibn Ruh]... and he had authored the book Kitab al-Taklif.”

— Shaykh al-Tusi, Kitab al-Ghaybah, Section: Al-Madhmumun (The Blameworthy Claimants)

This is the man who would become the greatest internal threat of the Minor Occultation.

The Root of Rot: The Iblis Syndrome

How does a man who is the “Gate to the Gate” become the cursed enemy of God?

The answer is one word:

Hasad (Envy).

When Husayn ibn Ruh was imprisoned by the Abbasids for a period of approximately five years, the leadership of the community had to be managed by proxies.

Shalmaghani expected to be the successor.

He looked at Husayn ibn Ruh—a man who was politically astute but perhaps less “bookish” in his eyes—and he succumbed to the logic of Iblis:

قَالَ أَنَا۠ خَيْرٌ مِّنْهُ ۖ خَلَقْتَنِى مِن نَّارٍ وَخَلَقْتَهُۥ مِن طِينٍ

“He [Iblis] said: ‘I am better than him. You created me from fire and You created him from clay.’”

— Quran, Surah Saad (the Chapter of the Letter Saad) #38, Verse 76

“Ana Khayrun Minhu” — “I am better than him.”

“I have written more books.

I have more students.

I have deeper knowledge.

Why is he the Deputy and not me?”

This is the Iblis Syndrome.

It is the delusion that divine appointment operates like a university faculty—that the one with the longest CV deserves the position.

Shalmaghani viewed the Deputyship as a political office to be earned by merit, not a divine trust to be received with humility.

Imam Ja’far al-Sadiq warns us of the corrosive nature of this disease:

إِنَّ الْحَسَدَ لَيَأْكُلُ الْإِيمَانَ كَمَا تَأْكُلُ النَّارُ الْحَطَبَ

“Indeed, envy eats away at faith just as fire eats away at firewood.”

— Al-Kulayni, Al-Kafi, Vol. 2, Kitab al-Iman wa al-Kufr (Book of Faith and Disbelief), Chapter on Envy, Hadith 1

Envy does not merely damage faith.

It consumes it.

It leaves nothing but ash.

Knowledge Without Purification

Shaheed Murtadha Mutahhari, calls this the danger of “Knowledge without Purification” (Ilm bila Tazkiyah).

He teaches us that a man can be a library of hadith, but if his ego is not tamed, that knowledge becomes fuel for the fire.

He explains:

«علم، ابزار است... اگر این ابزار به دست انسان ناصالح بیفتد، ضررش از آدم جاهل بیشتر است. چو دزدی با چراغ آید، گزیدهتر بَرَد کالا... علم بدون تزکیه، تیغی است در دست زنگی مست.»

“Knowledge is a tool... If this tool falls into the hands of an unrighteous person, his harm is greater than that of an ignorant person. [As the poet says]: ‘When a thief comes with a lamp, he picks the choicest goods.’... Knowledge without purification (Tazkiyah) is like a sword in the hand of a drunken madman.”

— Shaheed Murtadha Mutahhari, Ta’lim va Tarbiyat dar Islam (Education and Upbringing in Islam), Section: Tazkiyah-ye Nafs (Purification of the Soul), Sadra Publications.

The ignorant thief stumbles in the dark and takes whatever he bumps into.

The learned thief carries a lamp—and selects the finest goods.

The more knowledge he possesses, the greater his capacity for harm.

The Quran itself warns of this:

قَدْ أَفْلَحَ مَن زَكَّاهَا وَقَدْ خَابَ مَن دَسَّاهَا

“He has succeeded who purifies it [the soul], and he has failed who corrupts it.”

— Quran, Surah al-Shams (the Chapter of the Sun) #91, Verses 9-10

Notice the order:

Tazkiyah (purification) comes before success.

A man can memorise every hadith, master every science, write a hundred books—but if the soul is not purified, that knowledge becomes a weapon against its own possessor.

Shalmaghani was learned.

But he was not purified.

And so his learning destroyed him.

The Heresy: From Scholar to False Messiah

Envy, left untreated, metastasises.

To justify his rebellion against the Deputy, Shalmaghani had to invent a new theology.

He drifted into Ghuluww (Extremism)—the disease that has plagued the Shia community throughout history.

He began to claim Hulul (Incarnation)—that the Spirit of God had entered into him.

He told his followers that since they had reached the “Truth,” they no longer needed to pray or fast.

The outward rituals were merely symbols; the “enlightened” had transcended them.

He offered a seductive package: mysticism without rules, spirituality without submission, religion without responsibility.

This is the oldest trick in the book.

Every false prophet offers the same bargain:

“Follow me, and I will free you from the burden of obedience.”

But there is no Wilayah without submission.

There is no closeness to God without servitude.

The Imam himself said:

لَا يَنَالُ وِلَايَتَنَا إِلَّا بِالْعَمَلِ وَالْوَرَعِ

“Our Wilayah is not attained except through action and piety (Wara’).”

— Al-Kulayni, Al-Kafi, Volume 2

And regarding those who seek leadership for themselves:

مَنْ طَلَبَ الرِّئَاسَةَ هَلَكَ

“Whoever seeks leadership [for himself] perishes.”

— Al-Kulayni, Al-Kafi, Vol. 2, Chapter on Seeking Leadership (Talab al-Riyasah)

Shalmaghani sought leadership.

And he perished.

The Surgical Strike: The Letter from Prison

How did Husayn ibn Ruh respond?

Did he use Mudarat (Courtesy)?

Did he say, “Let us build bridges with our brother Shalmaghani”?

Did he offer dialogue and reconciliation?

No.

For the external enemy—the Abbasids—he used Courtesy.

For the internal cancer—Shalmaghani—he used the Scalpel.

Even from his prison cell, Husayn ibn Ruh smuggled out a letter (Tawqi’) from the Hidden Imam.

It was not a diplomatic communication.

It was a declaration of Bara’ah—total dissociation:

اعْرِفْ أَطَالَ اللَّهُ بَقَاءَكَ وَعَرِّفْ إِخْوَانَكَ... أَنَّ مُحَمَّدَ بْنَ عَلِيٍّ الْمَعْرُوفَ بِالشَّلْمَغَانِيِّ قَدِ ارْتَدَّ عَنِ الْإِسْلَامِ وَفَارَقَهُ... وَادَّعَى مَا كَفَرَ مَعَهُ بِالْخَالِقِ جَلَّ وَتَعَالَى... وَإِنَّا بَرِئْنَا إِلَى اللَّهِ تَعَالَى وَإِلَى رَسُولِهِ وَآلِهِ صَلَوَاتُ اللَّهِ عَلَيْهِمْ مِنْهُ، وَلَعَنَّاهُ، عَلَيْهِ لَعَائِنُ اللَّهِ.

“Know—may God prolong your life—and inform your brothers... that Muhammad ibn Ali, known as Al-Shalmaghani, has apostatised from Islam and separated from it... He has claimed that which implies disbelief in the Creator, Glorious and Exalted... Indeed, we dissociate ourselves (Bara’ah) before God and His Messenger and his Family... and we have cursed him; upon him be the curses of God.”

— Shaykh al-Tusi, Kitab al-Ghaybah, Section: The Letter regarding Shalmaghani

Husayn ibn Ruh ordered this letter to be read in the houses of the Shia.

He forced the community to choose: the “Celebrity Scholar” or the “Appointed Deputy.”

He cut the cancer out before it could kill the body.

This is the lesson:

Mudarat has limits.

When the threat is internal—when the cancer wears the garments of piety—courtesy becomes complicity.

The scalpel of Bara’ah must be applied without hesitation.

The Contemporary Mirror: The Scholarly Rift

This dynamic is not ancient history.

We have witnessed it in our own times, and the wounds are still bleeding.

The young people in our communities are fighting a war they do not fully understand—a war whose origins lie in a scholarly dispute that metastasised into something far more destructive.

We must understand what happened.

Not to condemn, but to learn.

Not to reignite hatred, but to explain why the fire started—so that perhaps, by God’s grace, it can finally be extinguished.

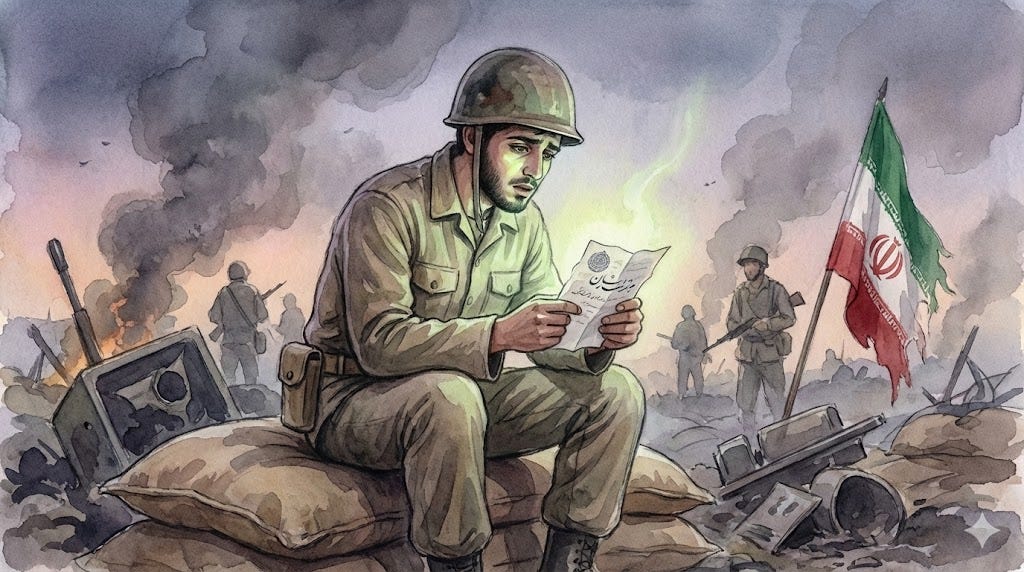

The Context: Two Visions of Governance

After the victory of the Islamic Revolution in 1979, a question arose:

How should the new Islamic state be governed?

Imam Khomeini articulated the doctrine of Wilayat al-Faqih—the Guardianship of the Jurist.

In this model, a single qualified scholar would serve as the Supreme Leader, providing unified religious and political guidance for the Muslim community.

Ayatullah Muhammad Shirazi, a respected scholar in his own right, held a different view.

He advocated for Shura al-Fuqaha—a Council of Jurists.

In this model, leadership would be collective rather than individual.

Let us be clear: both positions have scholarly precedent.

Both can be argued from the sources.

This was a legitimate intellectual disagreement—the kind that has always existed among scholars and always will.

When we reach the subject of Wilayat al-Faqih in our discussions, we will be examining in significantly more detail both of these, as well as other theories surrounding Islamic governance.

The problem was not the disagreement.

The problem was what happened next.

The Flashpoint: The War

In 1980, Saddam Hussein invaded Iran.

The world backed him—the Americans, the Soviets, the Arab states, the Europeans.

They provided him with weapons, intelligence, and chemical agents.

Iran stood alone.

By May 1982, through immense sacrifice, Iran had liberated its territory.

The city of Khorramshahr was reclaimed.

The question now was:

What next?

Imam Khomeini’s position was that the war must continue until the threat was neutralised.

Saddam had invaded once; if left in power, he would rearm and invade again.

The aggressor must be removed.

This was not expansionism—it was strategic necessity.

Ayatullah Muhammad Shirazi took a different view.

He argued that since Iranian territory had been reclaimed, the continuation of the war was no longer legitimate.

He issued a ruling—a fatwa—declaring further fighting to be Haram:

“إنَّ الحربَ كانت واجبةً للدفاع عن النفس والأرض، أما الآن وقد استرجعنا أراضينا، فإنَّ استمرارَ الحرب ودخولَ الأراضي العراقية هو قتالٌ بين المسلمين، وهو حرامٌ شرعاً ولا يجوزُ إهراقُ دماءِ المسلمين.”