[57] Mahdawiyyah (The Culminating Guidance) - The Era of Establishment - Part 2 - The Geopolitics of Waiting - Part 2 - The Shield (Taqiyyah) - The Shield Lowered - The Theology of Warfare

A series of discussions on the teachings of Imam Sadiq (sixth Imam of the Muslims), from the book Misbah ash-Sharia (The Lantern of the Path)

In His Name, the Most High

The Question That Would Not Wait

Last week, we traced the Shield through history.

We watched it raised in the Era of the Imams — when nine-tenths of religion was the wisdom of navigating hostile terrain.

We examined the Hasan-Husayn spectrum — the patience that preserves and the resistance that draws the line.

We witnessed the Safavid transformation — when the dust of Taqiyyah was wiped from the face of the faith and the secret became the slogan.

And we examined Heroic Flexibility — the Shield scaled to statecraft, the wisdom of the wrestler applied to nuclear negotiations, the JCPOA as Hudaybiyyah in modern form.

But as we closed that session, a question emerged that demanded its own answer:

Why?

Why is the Islamic Republic so adamant about not pursuing nuclear weapons?

The pressure is immense.

The sanctions are crippling.

The threats are constant — from the United States, from the Zionist entity, from the collective machinery of Western power.

Every strategic calculation would suggest that survival requires the ultimate deterrent.

Pakistan acquired it.

North Korea acquired it.

Israel — the very entity that threatens Iran daily — possesses hundreds of undeclared warheads.

Why not Iran?

Is this political calculation?

A judgment that the costs outweigh the benefits?

Is this diplomatic posturing?

A negotiating stance that might shift if circumstances change?

Or is there something deeper — something rooted in the very foundations of Islamic law, something that makes such weapons not merely unwise but forbidden?

Tonight, we answer this question.

And the answer will take us into territory that the critics of Islam have never understood — and that many Muslims themselves have not fully considered.

The Expansion of the Arc

When we began this exploration of Taqiyyah, we announced that it would span two sessions: the forging of the Shield, and its application.

But the material had other plans.

The application became two sessions — the historical record in Session 56, and tonight’s examination of when the Shield is lowered.

And even “The Shield Lowered” has proven too vast for a single evening.

There are two dimensions to this teaching.

The first concerns physical weapons — the bombs, the chemicals, the biological agents, the nuclear warheads.

The second concerns informational weapons — the lies, the manipulations, the sedition that poisons minds as surely as radiation poisons bodies.

Both are governed by the same principle:

Islam permits — even mandates — legitimate force.

But Islam forbids that which is indiscriminate, that which cannot distinguish friend from foe, that which destroys the very foundations it claims to protect.

Tonight, in Session 57, we examine the Theology of Warfare — the physical dimension.

Why weapons of mass destruction are forbidden.

Why the Nuclear Fatwa is not political posturing but theological necessity.

Why any jurist who takes Islamic principles seriously would reach the same conclusion.

Next week, in Session 58, we examine the Theology of Dissent — the informational dimension.

How Islam distinguishes legitimate protest from sedition.

How the same principle that forbids poisoning the land forbids poisoning the mind.

And we will complete the Defensive Movement by examining Makarim al-Akhlaq — the Noble Character — and asking what the believer does when the Shield is finally lowered for good.

But tonight: warfare.

Tonight: the weapons that Islam forbids.

Tonight: the answer to a question that has confused observers for decades.

The Accusation We Will Dismantle

There is an accusation that surfaces whenever the Nuclear Fatwa is discussed.

“It’s Taqiyyah,”

they say.

“Iran claims it doesn’t want nuclear weapons, but that’s just religious deception. They’re saying one thing publicly while secretly pursuing the bomb.”

This accusation reveals something important — but not about Iran.

It reveals that the accusers do not understand Islamic law.

They do not understand the tradition they claim to critique.

They assume that everyone operates by the same amoral calculus they themselves employ — that survival trumps principle, that power justifies any means, that religious commitments are merely decorative.

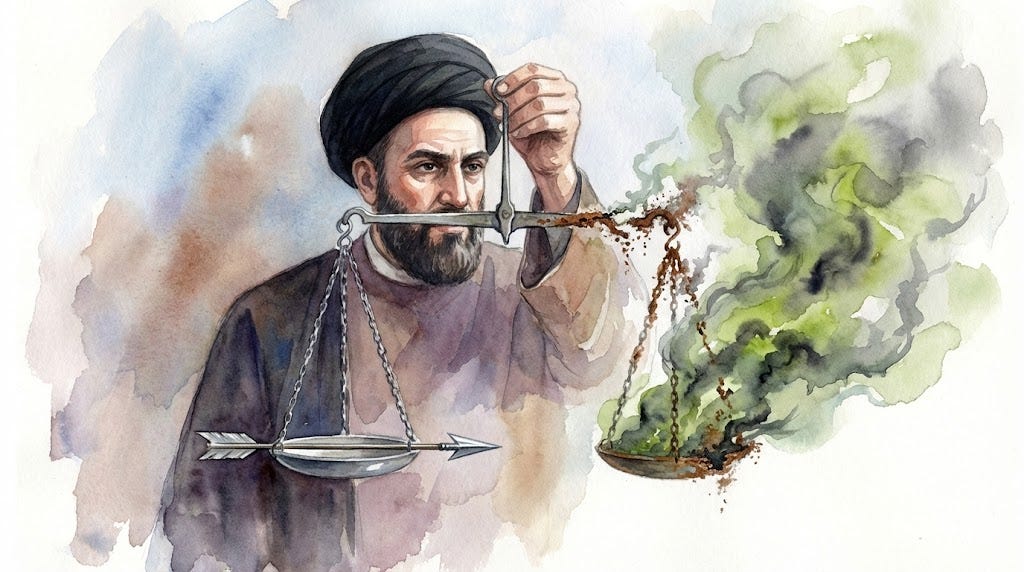

Tonight, we will show that the Nuclear Fatwa is not Taqiyyah.

It cannot be Taqiyyah.

Because Taqiyyah conceals a truth that exists.

But in this case, there is no hidden truth.

There is no secret desire for nuclear weapons that the Fatwa conceals.

The Fatwa expresses the only conclusion that Islamic jurisprudence can reach when its principles are applied to modern weapons technology.

It is not one scholar’s opinion.

It is the inevitable outcome of fourteen centuries of ethical reasoning about the limits of violence.

Any jurist operating within this tradition — Shia or Sunni, in Qom or Cairo, in Najaf or Madinah — who genuinely applies the sources would reach the same conclusion.

The accusation of Taqiyyah, in this case, is not insight into Iranian deception.

It is confession of the accuser’s own inability to imagine a value system that places principle above power.

What We Will Establish

Tonight, we build the case brick by brick.

We will examine the Quranic purpose of military preparation — and discover that the goal is deterrence, not massacre.

We will trace the classical prohibition on poison — and find that scholars a thousand years ago forbade exactly what nuclear weapons do today.

We will hear the Prophet’s instructions to his commanders — and understand that the limits he placed on seventh-century warfare make twenty-first-century weapons of mass destruction impossible to justify.

We will expand the category — showing that the prohibition covers not just nuclear weapons but any weapon with residual, indiscriminate harm: chemical, biological, radiological.

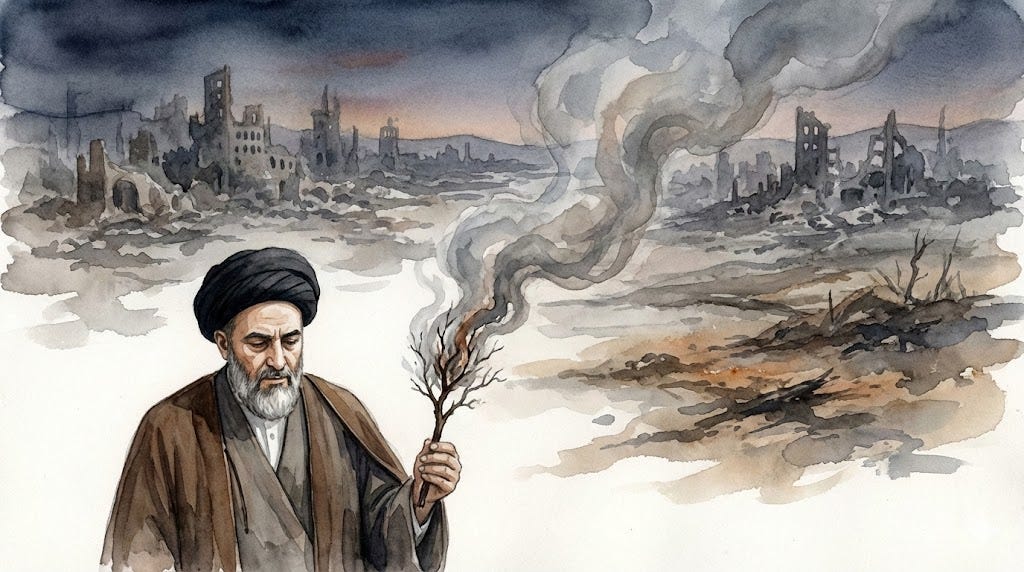

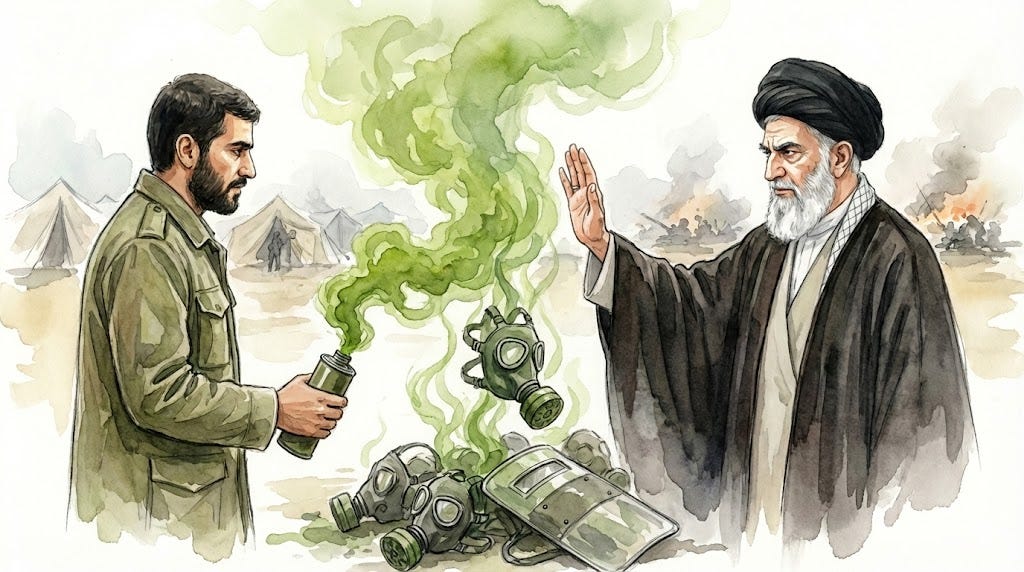

We will witness Imam Khomeini’s refusal to retaliate with chemical weapons even when Iran was being gassed by Saddam Hussein — and hear his reasoning:

“If we produce chemical weapons, what is the difference between us and Saddam?”

We will examine Imam Khamenei’s formal Fatwa — and understand why he classified it as a Primary Ruling that cannot change with circumstances.

We will survey the consensus of the living maraji’ — Ayatullah Sistani, Ayatullah Makarim Shirazi, Ayatullah Jawadi-Amoli — and see that this is not one man’s opinion but the agreed position of the tradition’s highest authorities.

We will address the Pakistan objection — and show why the existence of Pakistani nuclear weapons proves nothing about Islamic law.

And we will arrive at the conclusion that has been waiting for us since we began:

The Nuclear Fatwa is not Taqiyyah.

It is the inevitable conclusion of Islamic principles applied to modern technology.

It is not hiding a secret desire.

It is expressing a prohibition that was always there — waiting for the technology to arrive so that the ruling could be made explicit.

The Shield is lowered not to reveal a hidden weapon, but to declare a truth the world has refused to hear.

Islam forbids weapons of mass destruction.

Not because it is politically convenient to say so.

Because it is theologically impossible to say otherwise.

Video of the Majlis (Sermon/Lecture)

This is the video presentation of this write-up as a Majlis (part of the Truth Promoters Weekly Wednesday Majlis Program)

Audio of the Majlis (Sermon/Lecture)

This is the audio presentation of this write-up as a Majlis (part of the Truth Promoters Weekly Wednesday Majlis Program)

Recap

The Shield in Action

Last week, we took the Shield from the armoury into the field.

We had forged it in Session 55 — grounding Taqiyyah in the Quran, in the story of Ammar, in the Believer of Pharaoh’s household, in the linguistic connection to Taqwa, in the jurisprudential hierarchy that demands Tawriyah before falsehood.

In Session 56, we asked: How was this Shield actually carried?

Fitrah: The Shield in Creation

We began with Allamah Tabatabai’s remarkable argument in Al-Mizan.

Taqiyyah, he wrote, is not merely permitted by revelation.

It is inscribed in creation itself. It is one of the al-umur al-fitriyya — the natural matters — that the Fitrah of every sentient being dictates.

The chameleon shifts its colour.

The octopus releases its ink.

The deer freezes before the predator.

These creatures are not “lying” to their enemies.

They are surviving.

They are using the tools that God Himself placed in their nature.

And the same God who designed the chameleon revealed the Quran.

To mock Taqiyyah, we concluded, is to mock the design of the Creator.

The Mirror Opposites: Taqiyyah and Nifaq

We then dismantled the ancient slander — the accusation that Taqiyyah is simply hypocrisy by another name.

We showed that these concepts are not twins but opposites.

The Munafiq carries disbelief inside and wears Islam on his tongue.

He enters the community to destroy it.

He conceals evil under the appearance of good.

The Mutaqi carries faith inside and wears caution on his tongue.

He protects himself to serve the community.

He shields good from those who would destroy it.

One poisons.

The other preserves.

As Ayatullah Jawadi-Amoli wrote:

“Taqiyyah is the concealment of the Truth to preserve it, not to nullify it.”

The direction of movement is opposite.

The moral valuation is opposite.

The destination in the Hereafter is opposite.

Never again should these be confused.

The Historical Record

We traced the Shield through history.

In the Era of the Imams, we saw how Imam al-Baqir and Imam al-Sadiq built the school in the shadows — teaching carefully, to trusted students, under constant surveillance.

“Nine-tenths of religion is in Taqiyyah,”

the Imam said.

This was not exaggeration.

This was description.

The Shield made the school possible.

In the Hasan-Husayn Spectrum, we learned that Taqiyyah and Shahadah are not contradictions but responses to different conditions.

Imam Hasan made the treaty because the capacity for victory was not there; patience preserved the community.

Imam Husayn refused the bay’ah (allegiance) because silence would have buried Islam forever; resistance drew the line that can never be erased.

Same family.

Same commitment.

Different conditions, different responses.

In the Safavid Transformation, we witnessed the moment the Shield was lowered — at least in Iran.

Shah Ismail’s declaration in 1501, the scholars’ calculation that the “fear” had been removed,

Allamah Majlisi’s magnificent statement:

“The dust of Taqiyyah has been wiped from the face of the True School of Thought.”

We noted carefully that the Safavid kings were empire-builders using Shia identity as a political banner, not spiritual exemplars. But the scholars — Muhaqqiq al-Karaki, Allamah Majlisi, Mulla Sadra — used the political cover wisely.

As Shaheed Mutahhari later wrote:

“They captured the court; they were not captured by the court.”

Heroic Flexibility

Finally, we examined the Shield at the level of statecraft.

Imam Khamenei’s concept of Narm-e Qahramaneh — Heroic Flexibility — showed that strategic navigation does not disappear when you have power.

It transforms.

The wrestler who yields position to set up a counter-attack.

The Prophet who removed “Messenger of God” from the Hudaybiyyah treaty because peace was worth more than a symbolic victory.

The JCPOA was Hudaybiyyah in modern form. Iran agreed to limit what it was never pursuing anyway — a form of Tawriyah at the level of nations.

Iran complied; the IAEA verified; the West broke its word.

The flexibility was “heroic” because it never surrendered the kernel.

And when the dust settled, the world saw — those with eyes to see — who had kept their word and who had broken theirs.

The Question That Emerged

But as we closed, a question hung in the air:

Why is Iran so adamant?

Why, when faced with existential pressure, does the Islamic Republic refuse to pursue nuclear weapons?

Is it calculation?

Is it posturing?

Or is it something deeper — something rooted in the very foundations of Islamic law?

Tonight, we answer that question.

Tonight, we examine the Theology of Warfare.

And we discover that the Nuclear Fatwa is not strategy.

It is theology.

It is not hiding a truth.

It is expressing the only conclusion Islamic jurisprudence can reach.

Mahdawiyyah (The Culminating Guidance) - The Era of Establishment - The Geopolitics of Waiting - The Shield (Taqiyyah) - The Shield Lowered - The Theology of Warfare

The Nature of Conflict: Who Is the Enemy?

Before we can understand what weapons Islam permits and forbids, we must understand how Islam views conflict itself.

And here we encounter a perspective that differs profoundly from the assumptions of modern Western military doctrine.

The Myth of National War

The modern world operates on a fiction: that wars are fought between peoples.

“America versus Iran.”

“Israel versus Palestine.”

“The West versus Islam.”

This framing suggests that when nations go to war, entire populations are enemies of entire populations.

The American citizen is the enemy of the Iranian citizen.

The Israeli child is the enemy of the Palestinian child.

Every member of one nation stands opposed to every member of the other.

This is a lie.

And it is a lie with a purpose: it justifies the unjustifiable.

If the enemy is an entire population, then any weapon that destroys populations is legitimate.

If the Iranian people are the enemy, then sanctions that starve Iranian children are acceptable.

If the Palestinian nation is the enemy, then bombing refugee camps is reasonable.

The fiction of national war is the foundation upon which atrocities are built.

The Islamic View: Oppression, Justice, and the Sanctity of Souls

Islam sees the matter differently — and with far greater moral precision.

The Shia tradition, grounded in the teachings of the Imams and developed through centuries of jurisprudential reasoning, offers a framework that neither flattens moral distinctions nor abandons the protection of innocents.

This framework rests on three pillars:

First: Wars are initiated by systems of oppression.

Second: The just respond through legitimate defence.

Third: Yet even in the most righteous struggle, civilian populations retain their God-given sanctity.

Let us examine each.

The First Pillar: Wars Are Initiated by Systems of Oppression

The Quran is explicit about the nature of those who initiate conflict and spread corruption:

وَلَا تَرْكَنُوا إِلَى الَّذِينَ ظَلَمُوا فَتَمَسَّكُمُ النَّارُ

“And do not incline toward those who do wrong, lest you be touched by the Fire.”

— Quran, Surah Hud (the Chapter of Prophet Hud) #11, Verse 113

This verse became the foundation for Shaykh Murtadha al-Ansari’s analysis in Al-Makasib al-Muharramah (Forbidden Earnings) — a heavyweight text studied in the advanced stages of the Hawza.

In his discussion of I’anat al-Zalimin (Assisting the Oppressors), Shaykh Ansari establishes that the primary culpability for war lies with the Zalimin — the oppressors, the unjust, those who initiate aggression and spread corruption.

The tradition uses precise terminology:

Al-Zalimin — the oppressors, those who transgress against others.

Al-Mustakbirin — the arrogant powers, those who seek hegemony and domination.

These are the initiators of conflict.

These are the ones upon whom the burden of war falls.

The farmer, the shopkeeper, the grandmother — they did not sign the declaration of war.

They did not plan the invasion.

They did not profit from the aggression.

The system did.

The oppressors did.

And the Quran warns against even inclining toward them, let alone serving their purposes.

The Second Pillar: The Just Respond Through Legitimate Defence

If offensive war requires the presence of the Infallible Imam — and the scholars are unanimous that it does — then what remains for the believers in the era of Occultation?

Defence.

Resistance.

The protection of the community when it is attacked.

Ayatullah al-Udhma Sayyid Abu al-Qasim al-Khoei, perhaps the most influential jurist of the twentieth century, articulates this with precision in Minhaj al-Salihin (The Path of the Righteous):

الجهاد مع الكفار الدعوة إلى الإسلام، وهو المسمى بـ (الجهاد الابتدائي)، ولا يجب بل ولا يجوز إلا بشرط وجود الإمام المعصوم (ع) أو من يعينه لخوض الحرب.

“Jihad with the disbelievers to invite them to Islam, which is called (Initial Jihad), is not obligatory — in fact, it is not even permissible — except under the condition of the presence of the Infallible Imam (peace be upon him) or one whom he has specifically appointed to engage in the war.”

— Ayatullah al-Khoei, Minhaj al-Salihin, Volume 1, Book of Jihad

The implication is profound: the legal apparatus for wars of conquest is locked.

The key is held by the Hidden Imam, and until his return, offensive warfare for the expansion of territory is simply not available to the believers.

What remains is Jihad al-Difa’i — Defensive Jihad.

When someone attacks a Muslim country, the duty to defend is absolute and does not require the permission of a jurist or an Imam.

Imam Khamenei articulates the moral distinction with clarity:

ناك فرقان كبيران بين الحرب الدفاعية والهجومية من حيث المعنى والمحتوى. الفرق الأول هو أن الحرب الهجومية تقوم على التجاوز والعدوان، لكن الأمر ليس كذلك في الحرب الدفاعية.

“There are two major differences between a defensive and an offensive war in terms of meaning and content. The first difference is that an offensive war is based on transgression and aggression, but this is not the case with a defensive war.”

— Imam Khamenei, Official Statement, 21 October 2006, Khamenei.ir

The nature of Shia warfare in this era is therefore fundamentally reactive.

It is the response to aggression, not its initiation.

It is the shield raised against the sword, not the sword thrust at the innocent.

The Third Pillar: Haqq Against Batil — Without Flattening the Distinction

Here we must address a subtlety that lesser frameworks miss.

Some might hear “wars are initiated by oppressors” and conclude that all conflicts are merely power struggles — two sets of elites competing for dominance, with no moral distinction between them.

This is not the Islamic view.

Some conflicts genuinely are Haqq against Batil — Truth against Falsehood, Justice against Oppression.

And in such conflicts, the two sides are not morally equivalent.

Ayatullah Jawadi-Amoli, the premier philosopher-jurist of the Qom Hawza, articulates this principle in the context of contemporary events:

الحالة الراهنة التي واجهت فيها إسرائيل المسلمين ليست حرباً طائفية... إنها حرب بين الحق والباطل، أي حرب إسلامية.

“The current situation in which Israel faces Muslims is not a sectarian war... it is a war of right and wrong — that is, an Islamic war.”

— Ayatullah Jawadi-Amoli, Statement reported by ABNA (Ahlul Bayt News Agency), 21 October 2024

Harb al-Haqq wa al-Batil — the War of Right and Wrong.

This is not a framework that pretends all sides are equally culpable.

The aggressor is not morally equivalent to the defender.

The oppressor is not the same as the oppressed.

The one who erases truth is not equal to the one who preserves it.

Consider Karbala.

Was that “elites against elites”?

Was that merely two power centres competing for political dominance?

Never.

That was the Proof of God standing against the erasure of everything the Prophet had established.

That was Haqq — embodied in Imam Husayn — confronting Batil — embodied in the system of Yazid.

To flatten that distinction, to pretend that both sides were merely “elites” with competing interests, would be to misunderstand the very foundation of our tradition.

Karbala was not a power struggle.

It was the battle for the soul of Islam itself.

And yet — and this is the crucial point — even at Karbala, the civilian population of Damascus was not the enemy.

The women in the marketplaces of Syria did not vote for Yazid’s crimes.

The children playing in the streets of Kufa did not sign the letters of betrayal.

The elderly in their homes did not wield the swords that cut down the family of the Prophet.

They were governed by a system of Batil.

Many of them were themselves Mustad’afin — weakened, manipulated, unable to resist the powers that controlled them.

And so the principle holds: even when the cause is absolutely just, even when the enemy system is absolutely corrupt, the civilian population retains its sanctity.

The Spectrum of Culpability: Silence Is Not Innocence

But we must not overcorrect.

In emphasising that civilian populations are not legitimate military targets, we must not fall into the error of suggesting that all civilians are morally equivalent — that the one who actively resists oppression stands on the same ground as the one who watches in comfortable silence.

The tradition is precise on this matter.

In the Ziyarat Ashura — the visitation prayer for Imam Husayn that every believer knows — we recite:

وَلَعَنَ اللهُ أُمَّةً سَمِعَتْ بِذٰلِكَ فَرَضِيَتْ بِهِ

“And may God’s mercy be excluded from the nation that heard of this and was pleased with it.”

— Ziyarat Ashura

Consider the weight of this phrase: sami’at bidhalika — “heard of this.”

Not “participated in this.”

Not “wielded the swords.”

Simply heard.

And then: faradhiyat bih — “was pleased with it,” or more precisely, “acquiesced to it,” “accepted it,” “did not oppose it.”

The mercy of God should be removed from not only on those who struck the blows at Karbala.

It is removed from those who knew what was happening and chose silence.

Those who heard the news and did not raise their voices.

Those who could have protested, could have refused, could have made even the smallest gesture of opposition — and instead made their peace with the oppressor.

This is a moral judgment of the highest order.

It tells us that knowledge creates responsibility.

The one who genuinely does not know, who has no access to the truth, who is fed only propaganda and has no means to see through it — that person is in one category.

They are truly Mustad’af — weakened, unable to resist what they cannot even perceive.

But the one who knows?

The one who understands that an injustice is being committed?

The one who sees the oppression and chooses the comfort of silence?

That person bears a burden before God.

The Duty to Resist — In Whatever Form Is Possible

This does not mean every person must take up arms.

That may not be possible.

That may not be wise.

That may not be permitted by their circumstances.

But resistance takes many forms.

During the American war in Vietnam, millions of citizens protested in the streets.

They did not stop the war immediately — but they bore witness.

They refused to let the crime be committed in comfortable silence.

They fulfilled their duty.

During the invasion of Iraq in 2003, people across the world marched against a war built on lies.

They could not prevent the destruction — but they separated themselves from the guilt of acquiescence.

When they stand before God, they can say:

“I heard of this, and I was not pleased with it.

I opposed it with what capacity I had.”

There is the phenomenon of the “refusenik” — the soldier who refuses to serve in an unjust war, who accepts imprisonment rather than participation in oppression.

These individuals understand that when one is conscripted into injustice, the duty is to refuse, regardless of the personal cost.

Even smaller acts matter.

Writing to an elected official.

Making responsible social media posts that speak truth.

Having difficult conversations with family and neighbours.

Refusing to wave the flag when the flag is being used to cover crimes.

The capacity differs from person to person.

Not everyone can march.

Not everyone can refuse military service.

Not everyone has a platform.

But everyone who knows has a duty to do something — even if that something is simply refusing to celebrate, refusing to cheer, refusing to add their voice to the chorus of approval.

The Crucial Distinction: Moral Culpability Is Not Target Status

And yet — and this is essential — moral culpability before God does not transform a civilian into a legitimate military target.

The silent citizen of an oppressor nation bears a spiritual burden.

They will answer to God for their silence.

The prayer of being excluded from God’s mercy of Ziyarat Ashura applies to them.

But they are still not combatants.

They are still not wielding weapons.

They are still protected by the principle that Ayatullah Sistani articulated:

“Beware of holding a person accountable for the crime of another.”

The warrior cannot execute divine judgment.

The warrior cannot look into hearts and determine who was secretly pleased and who was secretly grieved.

The warrior cannot sort the silently complicit from the silently opposed.

And therefore, the warrior must operate on the external criterion: combatant or non-combatant.

Those who fight may be fought.

Those who do not fight may not be targeted.

The moral judgment belongs to God.

The jurisprudential limit binds the believer.

A nuclear weapon cannot distinguish between the citizen who protested and the citizen who cheered.

A chemical weapon cannot spare the refusenik while poisoning the war-supporter.

An indiscriminate weapon treats all souls as equivalent — and therefore cannot be calibrated to the moral reality that some bear greater guilt than others.

This is another reason such weapons are forbidden: they erase the very distinctions that the tradition insists upon.

They flatten the spectrum of culpability into a single category — “target” — and thereby commit injustice even against the unjust framework’s own logic.

The one who knew and remained silent will answer to God.

But they will answer to God — not to the bomb.

The Asymmetry of Culpability: Aggressor and Defender Are Not Equivalent

We must now address a question that sentimentalism often obscures:

Are the soldiers of the aggressor nation and the soldiers of the defending nation morally equivalent?

The answer is no.

And the tradition is emphatic on this point.

The Sacred Duty of Defence

For the one whose land is invaded, whose family is threatened, whose home is under attack — resistance is not merely permitted.

It is obligatory.

The classical texts are unambiguous. In Sharh al-Lum’ah al-Dimashqiyya, the standard textbook of the Hawza, the ruling is stated with precision:

وَيَجِبُ الدِّفَاعُ عَنِ النَّفْسِ وَالْحَرِيمِ وُجُوباً مُطْلَقاً مَعَ الْقُدْرَةِ وَالْأَمْنِ

“It is absolutely obligatory (Wajib Mutlaq) to defend one’s self (Nafs) and family (Harim) if one has the capability and reasonable prospect of success.”

— Al-Shahid al-Thani, Sharh al-Lum’ah al-Dimashqiyya, Volume 9, Chapter on Defence

This is not a right that may be exercised.

It is a duty that must be fulfilled.

Imam Khomeini reinforces this in Tahrir al-Wasilah:

دفاع از اسلام و ناموس مسلمین و جان و مال آنها بر هر شخصی که قدرت دارد واجب است... و در این امر احتیاج به اذن ولی امر نیست.

“Defending Islam, the honour of Muslims, and their lives and property is obligatory (Wajib) on every individual who has the power... and in this matter, there is no need for the permission of the Guardian Jurist (Wali al-Amr).”

— Imam Khomeini, Tahrir al-Wasilah, Volume 1, Kitab al-Amr bil-Ma’ruf

The defender does not need to wait for a fatwa.

The obligation is immediate, instinctive, and sacred.

And the one who dies fulfilling it attains the station of martyrdom.

The Prophet, peace be upon him and his family, said:

مَنْ قُتِلَ دُونَ مَالِهِ فَهُوَ شَهِيدٌ

“Whoever is killed in defence of his property is a Martyr (Shahid).”

— Al-Hurr al-Ameli, Wasail al-Shia, Volume 15, Hadith 19997

If martyrdom is granted for defending property, what of the one who defends his family?

His faith?

His homeland?

Imam Ali, Commander of the Faithful, peace be upon him, warned of the humiliation that comes from failing to defend:

مَا غُزِيَ قَوْمٌ قَطُّ فِي عُقْرِ دَارِهِمْ إِلَّا ذَلُّوا

“No people are ever attacked within the sanctity of their own home except that they are humiliated.”

— Nahj al-Balagha, Sermon 27

The defender who takes up arms against an aggressor is not morally equivalent to the aggressor’s soldier.

One fulfils a sacred obligation.

The other participates — whether knowingly or through wilful blindness — in transgression.

The Culpability of the Aggressor’s Soldier

But what of the soldier on the other side — the young man conscripted into an army of aggression, fed propaganda, told he fights for freedom when he fights for empire?

Here we must be precise.

Yes, he may be misled.

Yes, he may not fully understand the war he fights.

Yes, he may be a victim of the system that deployed him.

But he is not thereby absolved.

He had a choice.

He could have refused.

He could have become a refusenik — accepting imprisonment rather than participation in injustice.

He could have asked questions before pulling triggers.

He could have listened to the millions who protested the very war he chose to fight.

His blind obedience does not distribute his guilt away.

It compounds it.

Consider the chain: the soldier says,

“I was following orders.”

The officer says,

“I was following the general.”

The general says,

“I was following the politician.”

The politician says,

“I was following the people’s will.”

And the people say,

“We were misled by the media.”

At what point does someone take responsibility?

The tradition does not permit this infinite regress of excuse-making.

The one who fights in an unjust war bears the burden of that choice — even if he was deceived, even if he was pressured, even if he did not fully understand.

This is why Ayatullah Sistani, even while calling for compassion, reminds the fighters:

«وَاعْلَمُوا أَنَّ أَكْثَرَ مَنْ يُقَاتِلُكُم إِنَّمَا هُم ضَحَايَا قَدْ اسْتَهْوَتْهُم فِتَنُ طَائِفَةٍ مِنَ النَّاسِ، فَعَمِلُوا بِشُبَهٍ أَوْ أَوْهَامٍ... فَكُونُوا لَهُم نُصَحَاءَ مَا اسْتَطَعْتُم، تَكُونُوا بِذَلِكَ خَوَلًا لِلَّهِ فِي عِبَادِهِ.»

«فَإِنَّكُمْ بِالْكَفِّ عَنْهُم [عِندَ الْقُدْرَةِ] تَكُونُونَ أَحَقَّ بِالْبَقَاءِ وَأَقْرَبَ إِلَى النَّصْرِ.»

“Know that most of those who fight you are merely victims whom the seditions (Fitna) of a group of people have lured/led astray. They have acted upon doubts (Shubah) or illusions...

So be advisers/guides to them as much as you can; by doing so, you will be God’s agents regarding His servants.

...For by restraining yourselves from [killing] them [when you have the power], you become more worthy of survival and closer to [Divine] Victory.”

— Ayatullah Sistani, Advice and Guidance to the Fighters on the Battlefields (12 February 2015), Point 13

“Most of those who fight you are victims who have been led astray by others.”

Note carefully: he calls them victims — but he does not call them innocents.

He recognises their spiritual state — confused, manipulated, perhaps deserving of pity.

But he does not thereby erase their status as combatants who may be legitimately fought.

The aggressor’s soldier is a legitimate target.

This is not cruelty; it is the logic of defence.

If you cannot fight those who attack you, defence becomes meaningless.

But even here, the tradition calls for a certain compassion.

Fight them — yes. But recognise that many of them are themselves casualties of systems that exploit their loyalty and weaponise their courage.

Do not hate them as you would hate their masters.

And if they surrender, if they lay down their arms, if they cease to be combatants — then they cease to be targets.

The Immunity of the Aggressor’s Civilians

The soldier of the aggressor — misled or not — made a choice to fight. He bears the consequences of that choice.

But what of those who made no such choice?

What of the civilians of the aggressor nation — the grandmother, the shopkeeper, the child?

Here the tradition draws an absolute line.

The Quran establishes the principle:

وَلَا تَزِرُ وَازِرَةٌ وِزْرَ أُخْرَى

“No bearer of burdens shall bear the burden of another.”

— Quran, Surah al-An’am (the Chapter of the Cattle) #6, Verse 164

This is the Qa’ida Fiqhiyya — the Legal Maxim — that governs targeting.

A tax-paying citizen of an aggressor state cannot be killed for the decisions of their president.

A child cannot be bombed for the policies of a parliament.

A grandmother cannot be targeted because her nation’s army committed crimes.

Ayatullah Sistani makes this explicit:

وَاحْذَرُوا أَخْذَ امْرِئٍ بِجَرِيرَةِ غَيْرِهِ... وَلَا تَأْخُذُوا بِالنُّوَاصِي بِمَا قَدْ يَكُونُ بَيْنَكُمْ وَبَيْنَ قَوْمِهِمْ، فَإِنَّ ذَلِكَ لَيْسَ مِنْ سُنَنِ دِينِكُمْ.

“Beware of holding a person accountable for the crime of another... And do not punish them for what might exist between you and their people/leaders, for that is not from the traditions of your religion.”

— Ayatullah Sistani, Advice and Guidance to the Fighters on the Battlefields (12 February 2015), Points 5 and 14

The civilian of the aggressor nation — even if their taxes fund the bombs, even if their silence permits the war — remains legally protected.

They cannot be targeted.

They cannot be killed.

They cannot be treated as combatants.

Imam Khamenei articulates this distinction in the modern context:

ما با ملت آمریکا مشکلی نداریم؛ ما با دولت استکباری و سیاستهای غلط آن طرفیم. حساب مردم از حساب رژیمهای سلطهگر جداست.

“We have no problem with the American people; we are opposed to the Arrogant Government and its wrong policies. The account of the people is separate from the account of the domineering regimes.”

— Imam Khamenei, Speech to Air Force Commanders, February 8, 2019

When the crowds chant “Death to America,” they chant against the system — the Pentagon, the CIA, the sanctions regime, the machinery of empire.

They do not chant against the farmer in Kansas or the nurse in Ohio.

The account of the people is separate from the account of the regime.

This is why indiscriminate weapons are forbidden.

A nuclear bomb cannot distinguish between the Pentagon and the playground.

A chemical weapon cannot spare the nurse while poisoning the general.

These weapons treat an entire population as guilty — and thereby commit an injustice that the tradition absolutely forbids.

The True Mustad’afin

So who are the Mustad’afin — the truly weakened, the genuinely oppressed?

They are those who lack the power and the knowledge to resist.

The child born into an aggressor nation, who has no vote, no voice, no understanding of the crimes committed in her name — she is Mustad’af.

The elderly man in a care home, who cannot march, cannot protest, cannot do anything but watch the news with grief — he is Mustad’af.

The citizen who genuinely does not know — who has been so thoroughly propagandised that they cannot see through the lies, who lacks access to alternative information, who has been deliberately kept ignorant — they may be Mustad’af.

But the one who knows and chooses silence?

The one who could protest but finds it inconvenient?

The one who could refuse but fears the social cost?

They bear a moral burden — even if they remain legally protected from targeting.

And the one who actively fights in an unjust war?

He is not Mustad’af.

He is a combatant.

He may be fought.

And if he falls, he bears the weight of the choice he made.

The tradition is not naive.

It does not pretend all people are equally innocent.

It recognises degrees of culpability, chains of responsibility, the weight of choice.

But it refuses to collapse these distinctions into a single category called “target.”

The commander who ordered the invasion, the soldier who carried it out, the civilian who cheered it on, and the grandmother who wept in silence — these are not the same.

Their culpability differs.

Their fate before God differs.

And the weapons we use must be capable of respecting these differences.

Any weapon that cannot — any weapon that treats all souls as equivalent targets — violates the very framework that makes just war possible.

The Duty of Care: Ayatullah Sistani’s Code

And here is the principle that shapes everything that follows:

The defender retains a duty of care toward the aggressor’s civilian population.

Read that again, because it contradicts everything modern warfare assumes.

Even when you are defending yourself — even when you have every right, indeed obligation, to resist — you do not thereby acquire the right to slaughter innocents.

Ayatullah Sistani, in his Advice and Guidance to the Fighters on the Battlefields (2015), articulates this with the weight of the entire tradition behind him:

الله الله في النفوس، فلا يُستحلّنَّ منها ما حرّم الله إلا بحقّه، وما أعظمها من خطيئة أن يلقى الله المرء وقد تلطخت يده بدم امرئ بريء.

“By God! By God! Be mindful of human souls; do not let what God has made forbidden be deemed permissible except by right... What a great sin it is for a man to meet God while his hands are stained with the blood of an innocent person.”

— Ayatullah Sistani, Advice and Guidance to the Fighters on the Battlefields (12 February 2015), Point 4

And he continues:

الله الله في الحرمات كلها، فإياكم والتعرض لها أو انتهاك شيء منها بلسان أو يد، واحذروا أخذ امرئ بجريرة غيره.

“By God! By God! Be mindful of all things sacred; beware of attacking them or violating any of them with your tongue or hand, and beware of holding a person accountable for the crime of another.”

— Ayatullah Sistani, Advice and Guidance to the Fighters on the Battlefields (12 February 2015), Point 5

“Beware of holding a person accountable for the crime of another.”

This single phrase demolishes the logic of collective punishment.

The grandmother in Gaza did not bomb Haifa.

The child in New York did not impose sanctions on Iran.

The shopkeeper in London did not vote for the wars fought in his name — and even if he did, he was manipulated by a media ecosystem designed to manufacture consent.

These people are not legitimate targets.

They are not “acceptable collateral damage.”

They are human beings — souls created by God, possessing rights that do not evaporate simply because their government has committed crimes.

And Ayatullah Sistani makes the principle absolutely explicit:

ولا تقتلوا شيخاً، ولا صبياً، ولا امرأة، وإن كانوا من ذوي من يقاتلكم.

“Do not kill an elder, a child, or a woman, even if they are the relatives of those who fight you.”

— Ayatullah Sistani, Advice and Guidance to the Fighters on the Battlefields (12 February 2015)

Even the relatives of combatants are protected.

Even those with family ties to the enemy soldiers retain their sanctity.

The defender fights the system, not the population.

The defender targets the military apparatus, not the marketplace.

The defender strikes the command centre, not the kindergarten.

This is not weakness.

This is not naivety.

This is the Islamic understanding of what warfare is for and what limits it must respect.

The Purpose of Legitimate War

If war is not against populations, what is it for?

In the Islamic framework, legitimate warfare has specific purposes:

To repel aggression. When an enemy attacks, you have the right — indeed, the obligation — to defend yourself, your family, your community, your faith.

To remove oppression. When a tyrant brutalises a population, those with capacity may intervene to lift the oppression — not to occupy, not to colonise, but to liberate and then withdraw.

To re-establish deterrence. When an enemy has violated boundaries, you respond with sufficient force to make clear that such violations carry unacceptable costs — so that they do not happen again.

Notice what is absent from this list:

Conquest is not a legitimate purpose.

Expanding territory for the sake of empire is not Islamic — and in the era of Occultation, it is not even legally available.

Revenge is not a legitimate purpose. Punishing a population for the crimes of its leaders is not Islamic.

Economic exploitation is not a legitimate purpose. Securing resources through force is not Islamic.

And annihilation is never a legitimate purpose. The goal is to stop the aggression, not to exterminate the aggressor.

The Implication for Weapons

Now we can see why certain weapons are forbidden.

A weapon that cannot distinguish between the guilty commander and the innocent child violates the duty of care.

A weapon that destroys not just the military base but the surrounding city treats an entire population as the enemy — which they are not.

A weapon that poisons the land for generations punishes children not yet born for wars they had no part in.

A weapon that, once unleashed, cannot be controlled or recalled operates on the assumption that everyone in its radius is a legitimate target — an assumption Islam explicitly rejects.

The question is not merely:

“Is this weapon effective?”

The question is:

“Can this weapon respect the limits that God has placed on warfare?”

Can it distinguish combatant from non-combatant?

Can it strike the military target while sparing the innocent?

Can it be controlled, directed, stopped when the objective is achieved?

If the answer to any of these questions is no, then the weapon is not a tool of legitimate defence.

It is an instrument of indiscriminate slaughter.

And Islam forbids it.

Ayatullah Jawadi-Amoli states the conclusion plainly:

إن الرسالة الرسمية للدين والإنسانية هي أنه لا ينبغي إنتاج أسلحة الدمار الشامل.

“The official message of religion and humanity is that weapons of mass destruction should not be produced.”

— Ayatullah Jawadi-Amoli, Statement via Esra International Foundation

This is not one scholar’s opinion.

This is the convergence of the entire tradition — the Quran’s prohibition on corruption in the land, the Prophet’s instructions to his commanders, the classical jurists’ ban on poison, the contemporary maraji’s codes of conduct — all arriving at the same inevitable conclusion.

Weapons that cannot discriminate are weapons that cannot be used justly.

And what cannot be used justly has no place in the arsenal of the believers.

The Foundation Laid

This is the foundation upon which everything else rests.

Wars are initiated by systems of oppression — the Zalimin, the Mustakbirin — and the just respond through legitimate defence.

Some conflicts are genuinely Haqq against Batil, and we do not pretend otherwise.

The oppressor is not morally equivalent to the defender.

Yet even in the most righteous struggle, civilian populations retain their sanctity.

The masses are often Mustad’afin — victims of systems they do not control.

And no person may be held accountable for the crime of another.

The purpose of legitimate war is limited: repel aggression, remove oppression, restore deterrence — not annihilate, not conquer, not exploit.

And therefore: any weapon that by its nature cannot respect these limits is forbidden, regardless of how effective it might be.

This is not a modern invention.

This is not the opinion of a single scholar.

This is the framework that Islamic jurisprudence has operated within for fourteen centuries — now articulated with new clarity because the technology has forced the question.

And when we apply this framework to nuclear weapons, to chemical weapons, to biological weapons — to any weapon of mass destruction — there is only one possible conclusion.

But we are getting ahead of ourselves.

First, let us see what the Quran itself says about the purpose of military preparation.

The Quranic Purpose: Deterrence, Not Massacre

We have established the framework: warfare is between power structures, not peoples; the defender retains duties toward civilians; the purpose of legitimate war is limited.

Now let us see how the Quran itself articulates the purpose of military preparation.

And here we encounter a verse that has been misunderstood by enemies of Islam and misapplied by false claimants to Islamic authority alike.

The Verse: Surah Al-Anfal - The Chapter of the Spoils, 8th Chapter of the Quran, Verse 60

وَأَعِدُّوا لَهُم مَّا اسْتَطَعْتُم مِّن قُوَّةٍ وَمِن رِّبَاطِ الْخَيْلِ تُرْهِبُونَ بِهِ عَدُوَّ اللَّهِ وَعَدُوَّكُمْ

“And prepare against them whatever you are able of power and of steeds of war by which you may strike awe into the enemy of God and your enemy...”

— Quran, Surah Al-Anfal (the Chapter of the Spoils) #8, Verse 60

This verse commands military preparation.

There is no ambiguity about that.

The believer is not called to pacifism, not instructed to remain defenceless, not told to trust that God will protect those who refuse to protect themselves.

A’iddu — “Prepare.”

This is an imperative.

It is a command.

Ma astata’tum min quwwah — “Whatever you are able of power.”

Not some power.

Not minimal power.

Whatever you are capable of acquiring.

The command is to maximise defensive capacity.

The critics of Islam stop here.

“You see?” they say.

“Islam commands military buildup. Islam is a religion of war.”

But they have not read the rest of the verse.

They have not asked the question that determines everything:

For what purpose?

The Key Word: Turhibuna

The verse does not say: taqtuluna — “that you may kill them.”

The verse does not say: tudammiruna — “that you may destroy them.”

The verse does not say: tastaw’ibuna — “that you may absorb/conquer them.”

The verse says: turhibuna — “that you may strike awe into them.”

This single word — turhibuna — unlocks the entire Islamic philosophy of military power.

The root is ر-ه-ب (ra-ha-ba), which carries the meaning of fear, awe, reverence.

The form used here is causative: to cause fear, to induce awe, to create in the enemy a psychological state that deters them from aggression.

This is not terrorism.

This is not intimidation for its own sake.

This is strategic deterrence — the use of evident strength to prevent conflict before it begins.

The Wisdom of Deterrence

Consider what the verse is actually teaching.

If you are weak, the enemy will attack.

They will calculate that the benefits of aggression outweigh the costs, and they will strike.

If you are strong — if you possess power that the enemy can see and must respect — they will calculate differently.

The costs of aggression become prohibitive.

The attack never comes.

The purpose of military preparation, according to this verse, is not to wage war.

It is to prevent war.

Not to kill the enemy.

But to make the enemy decide that attacking you is not worth the price.

This is turhibuna.

This is the Quranic concept of deterrence.

Allamah Tabatabai: The Tafsir al-Mizan Interpretation

In Al-Mizan, Allamah Tabatabai examines this verse with his characteristic precision.

He writes:

وَالْإِرْهَابُ: الْإِخَافَةُ، وَهُوَ رَمْيُ الرَّوْعِ فِي الْقَلْبِ لِيَكُفَّ عَمَّا يَرِيدُهُ مِنَ الشَّرِّ وَالْفَسَادِ.

“Al-Irhab means: instilling fear; it is the casting of alarm into the heart so that he may refrain from the evil and corruption he intends.”

— Allamah Tabatabai, Al-Mizan fi Tafsir al-Quran, Volume 9, Commentary on Verse 8:60

Notice the logic: the fear is not an end in itself. It is instrumental.

The purpose is liyakuffa — “so that he may refrain” — amma yuriduhu min al-sharr — “from the evil he intends.”

The enemy intends aggression.

The enemy plans corruption.

The fear induced by your strength causes him to abandon those plans.

The war that never happens because you were strong enough to deter it — this is the goal.

Ayatullah Makarim-Shirazi: The Tafsir-e Namuneh Interpretation

In Tafsir-e Namuneh (The Exemplary Exegesis), Ayatullah Makarim-Shirazi articulates this principle with remarkable clarity.

His commentary on this verse explicitly identifies the purpose of military preparation as psychological — to extinguish the very thought of aggression in the enemy’s mind before it can manifest into action.

He writes:

هدف از این آمادگی، در هم کوبیدن دشمن و نابودی او نیست، بلکه هدف آن است که دشمنان خدا و شما از این آمادگی بترسند و فکر تجاوز به شما را در مغز خود نپرورانند.

تعبیر به “تُرْهِبُونَ” (آنها را میترسانید) دلیل روشنی بر این است که هدف نهایی، جلوگیری از وقوع جنگ است، نه انجام جنگ. زیرا وقتی دشمنِ منطقی، قدرت شما را ببیند و بداند که در صورت حمله ضربه مهلکی خواهد خورد، از حمله صرفنظر میکند. این همان چیزی است که امروز به آن “نیروی بازدارنده” میگویند.

“The goal of this preparedness is not to crush or annihilate the enemy; rather, the goal is that the enemies of God and your enemies should fear this preparedness and should not nurture the thought of aggression against you in their minds.

The expression ‘Turhibuna’ (’You strike fear into them’) is clear proof that the ultimate goal is the prevention of war, not the execution of war. Because when a rational enemy sees your power and knows that in the event of an attack they will suffer a fatal blow, they will abandon the attack. This is exactly what is referred to today as ‘Deterrent Force’ (Niru-ye Bazdarandeh).”

— Ayatullah Makarim Shirazi, Tafsir Namuneh, Volume 7, Commentary on Surah Al-Anfal, Verse 60

Notice what Ayatullah Makarim-Shirazi is establishing here.

The goal is not — explicitly not —

“to crush or annihilate the enemy.”

The goal is that the enemy

“should not nurture the thought of aggression in their minds.”

The war you prevent is worth more than the war you win.

And the term he uses — Niru-ye Bazdarandeh — “Deterrent Force” — places this Quranic teaching squarely within the framework of modern strategic doctrine.

This is not medieval thinking awkwardly applied to modern circumstances.

This is a principle articulated fourteen centuries ago that anticipated what military strategists would only later formalise.

Strength that deters.

Power that prevents.

Preparation that makes aggression unthinkable.

This is turhibuna.

This is the Quranic purpose of military preparation.

Imam Khamenei: The Contemporary Application

Imam Khamenei has returned to this verse repeatedly in explaining the Islamic Republic’s defence doctrine.

In a speech to commanders of the armed forces, he articulated the principle with clarity:

دستور قرآن این است: وَ اَعِدّوا لَهُم مَا استَطَعتُم مِن قُوَّةٍ وَ مِن رِباطِ الخَیلِ تُرهِبونَ بِه عَدُوَّ اللهِ وَ عَدُوَّکُم. معنای «تُرهِبونَ بِه» این نیست که آنها را بترسانید تا برای شما حاشیه امن درست شود؛ نه، آنها را بترسانید تا به شما حمله نکنند. اگر نترسند، حمله میکنند.

“The Quran’s command is this: ‘And prepare against them whatever you are able of power...’ The meaning of ‘Turhibuna bihi’ (strike awe thereby) is not that you should terrify them just to create a safe margin for yourselves; no, make them fear so that they do not attack you. If they do not fear, they will attack.”

— Imam Khamenei, Speech to Commanders of the Army of the Islamic Republic, April 18, 2012

The logic is simple, and it is ancient, and it is Quranic:

Weakness invites aggression. Strength deters it.

Prepare whatever power you can — not to wage wars of conquest, but to ensure that the enemy calculates incorrectly if he dreams of attacking you.

The Scope of “Power”

One more element of Allamah Tabatabai’s analysis deserves attention.

The verse says: ma astata’tum min quwwah — “whatever you are able of power.”

The word quwwah (power) is indefinite, and Allamah Tabatabai notes the significance:

قَوْلُهُ تَعَالَى: (مِنْ قُوَّةٍ) ... نَكِرَةً فِي سِيَاقِ الشَّرْطِ تُفِيدُ الْعُمُومَ، فَيَشْمَلُ كُلَّ مَا يَتَقَوَّى بِهِ فِي الْحَرْبِ مِنْ أَنْوَاعِ السِّلَاحِ وَغَيْرِهَا.

“The statement of the Almighty: (min quwwatin / ‘of power’)... is indefinite in a conditional context, which denotes generality. Thus, it includes everything by which one gains strength in war, regarding types of weaponry and other things.”

— Allamah Tabatabai, Al-Mizan fi Tafsir al-Quran, Volume 9

The verse mentions “steeds of war” — the military technology of seventh-century Arabia.

But the principle is not bound to horses.

It extends to “everything by which one gains strength in war.”

In the modern era, this includes missiles and aircraft, cyber capabilities and satellite systems, industrial capacity and scientific knowledge.

The command to prepare “power” is not frozen in the past.

It adapts to each era’s technological reality.

The Critical Limit

But here is what must not be missed:

The command to prepare power is governed by the purpose stated in the same verse.

Turhibuna — to deter.

Not taqtuluna — to kill.

Not tubiduna — to annihilate.

The power you prepare must serve the purpose of deterrence.

The moment a weapon cannot serve that purpose — the moment it can only destroy indiscriminately, only massacre, only annihilate — it falls outside the Quranic command.

Think about this carefully.

A precision missile that can strike a military headquarters serves turhibuna.

The enemy knows you can hit his command centre; he is deterred from aggression.

A nuclear warhead that obliterates a city does not serve turhibuna.

It serves ibada — extermination.

It does not deter aggression; it annihilates populations.

It does not create calculated fear in enemy commanders; it murders grandmothers and schoolchildren.

The enemy’s general is not deterred by the threat of nuclear war.

He has a bunker.

He may survive.

The enemy’s population — the Mustad’af, the innocents, the people who never chose the war — they are the ones who will burn.

This is not turhibuna.

This is not the Quranic purpose of military preparation.

This is something else entirely.

And Islam forbids it.

The Principle Established

Let us be clear about what we have established.

The Quran commands military preparation.

This is not optional.

The believer is not called to be defenceless.

But the Quran specifies the purpose: deterrence.

The goal is to prevent war, not to wage it; to make aggression too costly to attempt, not to slaughter populations.

And therefore: any weapon that can only be used for indiscriminate destruction — that cannot serve the purpose of deterrence without crossing into annihilation — falls outside the Quranic command.

The verse that commands strength is the same verse that limits what kind of strength is permissible.

A’iddu — prepare.

Turhibuna — to deter.

Not to massacre.

Not to exterminate.

Not to poison the earth for generations.

To deter.

And any weapon that cannot serve that purpose — that can only destroy without distinction, only kill without limit, only harm without end — is not the “power” the Quran commands.

It is something the Quran forbids.

Now let us see how the classical scholars, long before nuclear weapons existed, articulated precisely this principle.

The Classical Prohibition: Poison in the Lands

We have established the Quranic framework: military preparation is commanded, but its purpose is deterrence, not annihilation.

Now we descend from the Quran to the jurisprudential tradition — the centuries of scholarly reasoning that translated Quranic principles into practical rulings.

And here we discover something remarkable.

Long before nuclear weapons existed, long before chemical warfare was industrialised, long before biological agents were weaponised — the scholars of Islam had already articulated the principle that forbids them all.

The principle was simple: you may not poison the enemy’s lands.

And that principle, applied to modern technology, yields only one conclusion.

The Antiquity of the Ruling

Some imagine that the prohibition on weapons of mass destruction is a modern invention — a twentieth-century response to Hiroshima and Nagasaki, a reaction to the horrors of chemical warfare in the trenches of Europe.

It is not.

The prohibition is a thousand years old.

It was articulated by scholars who had never seen a mushroom cloud, never witnessed nerve gas, never imagined a weapon that could render a city uninhabitable for generations.

And yet they articulated it — because they understood the principle.

They understood that some methods of warfare are inherently illegitimate, regardless of how effective they might be.

They understood that the ends do not justify all means.

They understood that there are lines which must not be crossed, even in the defence of the faith.

Let us hear their voices.

Shaykh Al-Tusi: Al-Nihayah

Shaykh Abu Ja’far Muhammad ibn al-Hasan al-Tusi — known as Shaykh al-Ta’ifa, the Shaykh of the Sect — died in 1067 CE.

He was among the most towering figures in Shia intellectual history, author of two of the Four Books of hadith, founder of the Hawza of Najaf, systematiser of Shia jurisprudence.

In his work Al-Nihayah fi Mujarrad al-Fiqh wa al-Fatawa, in the Book of Jihad, he addresses the permissible methods of warfare.

He writes:

و یجوز قتال الکفار بسائر أنواع القتل... إلا السـم، فإنه لا یجوز أن یلقی فی بلادهم السم.

“It is permissible to fight the disbelievers with all types of killing... except for poison; for it is certainly not permissible to cast poison into their lands.”

— Shaykh Al-Tusi, Al-Nihayah fi Mujarrad al-Fiqh wa al-Fatawa, Volume 1, Book of Jihad

Consider what Shaykh Al-Tusi is saying.

“All types of killing” — the sword, the arrow, the spear, the siege, the cavalry charge.

These are permissible.

War is war, and the enemy combatant may be fought with the weapons of war.

“Except poison.”

This single exception opens a vast space of moral reasoning.

Why is poison different?

Because poison does not distinguish.

It seeps into wells and kills whoever drinks — soldier or child, combatant or grandmother.

It spreads through the land and destroys whatever it touches — crops that feed the innocent, animals that belong to farmers who never raised a sword.

Poison cannot be aimed.

It cannot be controlled.

It cannot be told:

“Kill only the soldiers; spare the civilians.”

And therefore, it is forbidden.

A thousand years before Hiroshima, the principle was established.

Al-Lum’ah al-Dimashqiyyah: The Standard Textbook

If Shaykh Al-Tusi established the principle, Al-Lum’ah al-Dimashqiyyah codified it for generations of students.

This work, written by Al-Shahid al-Awwal (the First Martyr) and extensively commented upon by Al-Shahid al-Thani (the Second Martyr), is the backbone of the intermediate Hawza curriculum.

Almost every Shia cleric has studied these texts.

Almost every scholar has memorised these rulings.

In the Book of Jihad, under the section on the Etiquette of War (Adab al-Harb), the text states:

وَيَجُوزُ الْمُحَارَبَةُ بِكُلِّ شَيْءٍ ... إِلَّا السَّمَّ، فَإِنَّهُ يَحْرُمُ إِلْقَاؤُهُ فِي بِلَادِهِمْ، قِيلَ: مُطْلَقاً، وَقِيلَ: إِلَّا لِلضَّرُورَةِ، وَالْأَوَّلُ أَظْهَرُ.

“It is permissible to fight with anything... except poison; for it is forbidden to cast it into their lands. It is said [by some scholars]: ‘Absolutely [forbidden under any condition],’ and it is said: ‘Except for necessity.’ The first opinion [Absolute Prohibition] is the more apparent/correct view.”

— Al-Lum’ah al-Dimashqiyyah (with Al-Rawdah al-Bahiyyah commentary), Volume 2, Chapter on Jihad

This passage is critical for understanding the strength of the prohibition.

The text acknowledges that there are two scholarly opinions.

Some said the prohibition is absolute — no exception, no circumstance, no necessity overrides it.

Others said that in cases of extreme necessity (darurah), an exception might be made.

And then the text renders judgment: al-awwal adh’har — “the first opinion is more apparent/correct.”

The absolute prohibition is the stronger position.

Even necessity does not override it.

This is not a minor detail.

In Islamic jurisprudence, the principle of necessity (darurah) permits many things that are otherwise forbidden — eating pork to avoid starvation, speaking words of disbelief under torture.

Necessity is a powerful legal tool.

But here, the scholars ruled that necessity does not permit the use of poison.

Why?

Because the harm is too great.

The indiscriminate nature of the weapon means that using it — even in desperate circumstances — would cause a greater evil than it prevents.

This ruling, established centuries ago, anticipates exactly the moral calculus that applies to nuclear weapons today.

Tahdhib al-Ahkam: The Hadith Foundation

The jurisprudential ruling does not emerge from thin air.

It rests on a foundation of hadith — the reported words and actions of the Prophet and the Imams.

In Tahdhib al-Ahkam, one of the Four Books of Shia hadith compiled by Shaykh Al-Tusi himself, we find the Prophetic instruction that underlies the ruling.

The hadith is narrated from Imam Ja’far al-Sadiq, peace be upon him, who reported from the Messenger of God, peace be upon him and his family:

عَنْ أَبِي عَبْدِ اللَّهِ (ع) قَالَ: قَالَ رَسُولُ اللَّهِ (ص) ... وَ لَا تُلْقُوا السَّمَّ فِي بِلَادِ الْمُشْرِكِينَ.

“From Abu Abdillah [Imam Sadiq], he said: The Messenger of God said... ‘And do not cast poison into the lands of the polytheists.’”

— Al-Tusi, Tahdhib al-Ahkam, Volume 6, Kitab al-Jihad, Chapter on the Conduct of the Imam, Hadith 22

This is not a later scholarly interpretation.

This is a direct Prophetic command, transmitted through the Imam, recorded in one of the most authoritative hadith collections of the Shia tradition.

“Do not cast poison into their lands.”

Not: “Do not cast poison unless necessary.”

Not: “Do not cast poison unless they use it first.”

Not: “Do not cast poison unless you are losing the war.”

Simply: “Do not cast poison into their lands.”

The command is absolute.

The prohibition is unconditional.

And the scholars who built the jurisprudential tradition understood it as such.

The Logic of the Prohibition

Why this absolute stance?

Why is poison treated differently from other weapons?

The classical scholars did not always articulate their reasoning explicitly — the texts often state rulings without extensive justification.

But the logic is implicit in the ruling itself, and later scholars have made it explicit.

The prohibition rests on several interlocking principles:

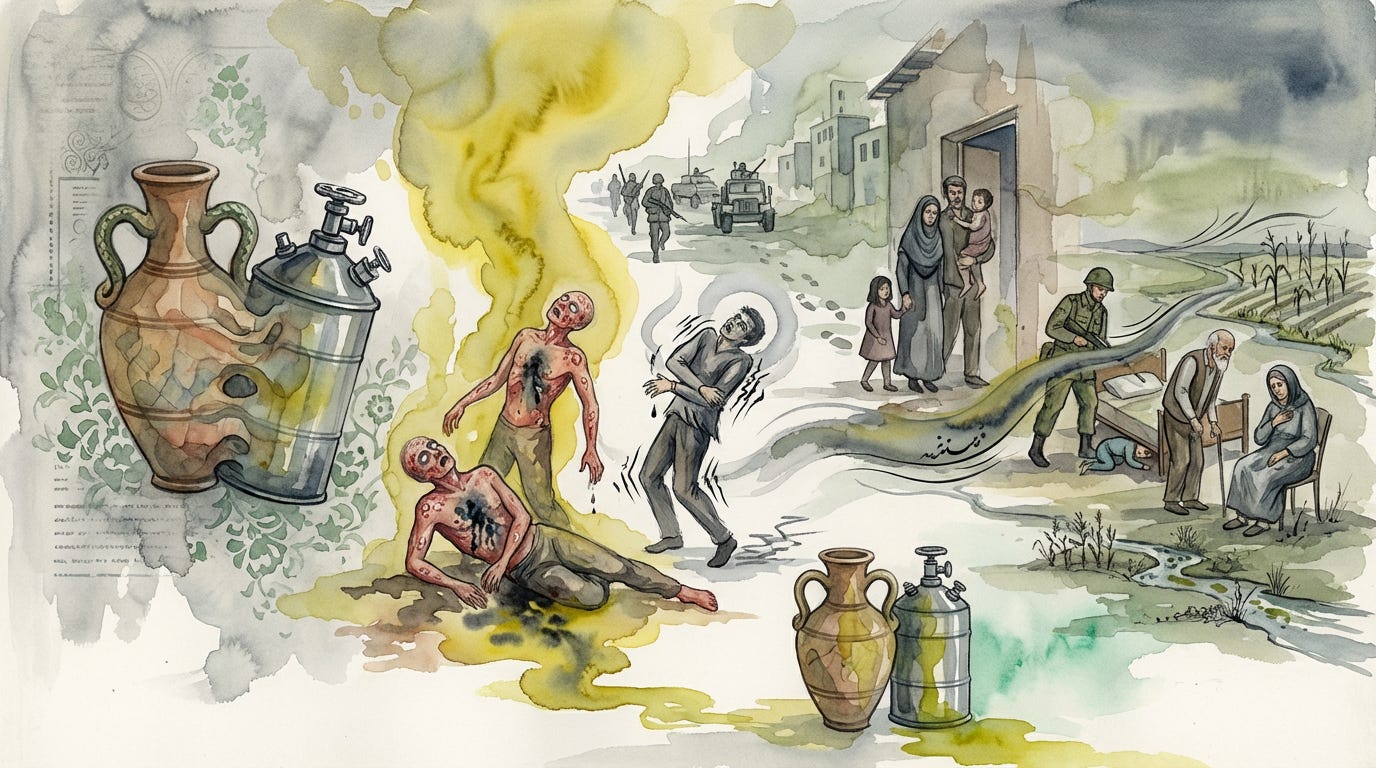

First: Indiscriminate Harm

Poison cannot distinguish between combatant and non-combatant.

When you poison a well, you do not know who will drink from it.

The enemy soldier may drink — but so may his wife, his children, the elderly, the sick, the traveller who has no part in the war.

The principle of discrimination — that you may target those who fight but must spare those who do not — is impossible to observe with poison.

Second: Uncontrollable Spread

Once poison is released, it cannot be recalled.

It spreads according to its own nature — through water, through soil, through air.

The one who releases it cannot control where it goes or whom it harms.

This loss of control is itself a moral problem.

The warrior is responsible for the consequences of his actions.

But how can he be responsible for consequences he cannot predict or control?

Third: Environmental Destruction

Poison does not only kill people.

It kills the land.

It destroys crops, contaminates water sources, renders soil barren.

It harms the creation that God has entrusted to human stewardship.

The Quran warns against those who “spread corruption in the land, destroying properties and lives”.

وَإِذَا تَوَلَّىٰ سَعَىٰ فِي الْأَرْضِ لِيُفْسِدَ فِيهَا وَيُهْلِكَ الْحَرْثَ وَالنَّسْلَ ۗ وَاللَّهُ لَا يُحِبُّ الْفَسَادَ

When he gains power, he strives to spread corruption on earth, destroying properties and lives. God does not like corruption.

— Quran, Surah al-Baqarah (the Chapter of the Cow) #2, Verse 205

Poison does precisely this — and on a scale that no ancient weapon could match.

Fourth: Generational Harm

The effects of poison do not end when the war ends.

Contaminated land remains contaminated.

Children born after the peace treaty inherit the consequences of the poisoned water their parents drank.

This violates a fundamental principle: that each soul bears only its own burden.

The child who was not yet born when the poison was released bears the burden of a war he had no part in.

The Modern Application

Now consider: what is a nuclear weapon if not poison on an unimaginable scale?

The radiation released by a nuclear detonation does not distinguish soldier from civilian.

It spreads through the air, the water, the soil.

It cannot be controlled or recalled once released.

It destroys not only the immediate targets but the environment for miles around.

And its effects persist for generations — cancers, birth defects, genetic damage passed from parent to child.

Everything the classical scholars said about poison applies to nuclear weapons — but multiplied a thousandfold.

And the same is true of chemical weapons, of biological weapons, of any weapon that operates through indiscriminate, uncontrollable, persistent harm.

The scholars who wrote a thousand years ago could not have imagined a nuclear warhead.

But they articulated the principle that governs it.

They said:

“Do not cast poison into their lands.”

And when you ask what a nuclear weapon is — what it does, how it operates, whom it harms — the only honest answer is: it is poison.

It is poison cast not into a single well, but into an entire city.

It is poison that spreads not through a single water source, but through the atmosphere itself.

It is poison that persists not for months, but for generations.

The ruling was established a thousand years ago.

The application to modern weapons is not innovation.

It is recognition.

The Prophetic Instructions: Rules of Engagement

We have traced the prohibition from the Quran through the classical jurists.

Now we go to the source that underlies both: the direct instructions of the Prophet himself, peace be upon him and his family.

For the prohibition on poison is not an isolated ruling.

It is part of a comprehensive framework — a set of rules governing the conduct of warfare that the Prophet established and that the Imams transmitted.

These rules reveal something profound about the Islamic conception of violence: that it is never unlimited, never unrestrained, never a license to do whatever achieves victory.

War, in Islam, has boundaries.

And those boundaries exist to protect precisely those whom the fog of war makes most vulnerable.

The Hadith of Rules

In Wasail al-Shia, the comprehensive hadith collection compiled by Al-Hurr al-Ameli, we find a hadith that enumerates the Prophet’s instructions to his commanders.

The hadith is extensive, but its key passages establish the framework:

... وَ لَا تَقْتُلُوا شَيْخاً فَانِياً وَ لَا صَبِيّاً وَ لَا امْرَأَةً وَ لَا تَغُلُّوا ... وَ لَا تُحْرِقُوا النَّخْلَ وَ لَا تُغْرِقُوهُ بِالْمَاءِ وَ لَا تَقْطَعُوا شَجَرَةً مُثْمِرَةً وَ لَا تُحْرِقُوا زَرْعاً ... وَ لَا تُلْقُوا السَّمَّ فِي بِلَادِ الْمُشْرِكِينَ

“...And do not kill a decrepit old man, nor a child, nor a woman; and do not steal from the spoils... and do not burn the palm trees, nor drown them with water, nor cut down a fruit-bearing tree, nor burn the crops... and do not cast poison into the lands of the polytheists.”

— Al-Hurr al-Ameli, Wasail al-Shia, Volume 15, Chapter on the Rules of Jihad, Hadith 19907

Let us examine each instruction, for each reveals a principle.

The Protection of Non-Combatants

“Do not kill a decrepit old man, nor a child, nor a woman...”

The elderly man who can no longer fight.

The child who has not yet reached the age of combat.

The woman who is not bearing arms.

These are not combatants.

They are not threats.

They may be citizens of the enemy nation, they may even support the enemy’s cause — but they are not wielding swords, not manning defences, not posing immediate danger.

And therefore, they may not be killed.

This is the principle of distinction — the requirement that the warrior distinguish between those who fight and those who do not, between legitimate military targets and protected civilians.

Notice: the Prophet did not say “minimise civilian casualties.”

He did not say “make reasonable efforts to avoid non-combatants.”

He said: do not kill them.

The command is categorical.

The modern military doctrine of “collateral damage” — which treats civilian deaths as regrettable but acceptable side effects of military operations — finds no support in this hadith.

The Prophet’s command is not to minimise.

It is to prohibit.

The Protection of Nature

“Do not burn the palm trees, nor drown them with water, nor cut down a fruit-bearing tree, nor burn the crops...”

Here the protection extends beyond human beings to the natural world itself.

The palm tree provides dates — food for the people, including the people you are fighting.

The fruit-bearing tree provides sustenance that will be needed when the war ends.

The crops in the field will feed families who had no part in the decision to go to war.

To destroy these is to wage war not against the enemy army but against the land itself — against the future, against the children who will need that food, against the creation that God entrusted to human care.

This is the principle of environmental protection — the recognition that war, however necessary, must not destroy the basis upon which human life depends.

And notice the specificity:

“nor drown them with water.”

This refers to a tactic of flooding irrigation channels to kill the roots of trees — a slower destruction than fire, but destruction nonetheless.

The Prophet forbade even this.

Not just dramatic destruction, but quiet destruction.

Not just immediate ruin, but long-term harm.

The prohibition is comprehensive.

The Prohibition of Poison

“...and do not cast poison into the lands of the polytheists.”

We have already examined this instruction in the context of jurisprudence.

But here we see it in its original setting — as part of a comprehensive framework of restraint.

The Prophet did not issue this instruction in isolation.

He placed it alongside the protection of non-combatants and the protection of nature.

The logic becomes clear: poison violates both principles simultaneously.

It kills non-combatants — because it cannot distinguish who drinks from the well.

It destroys nature — because it contaminates the water, the soil, the ecosystem.

Poison is, in a sense, the paradigmatic forbidden weapon — the weapon that violates every principle the Prophet established.

And that is precisely why the scholars gave it such absolute treatment.

The Underlying Logic

Step back and consider what these instructions reveal about the Islamic conception of warfare.

War is permitted — in defence, in resistance to oppression, in protection of the faith and the community.

This is not a pacifist tradition.

But war is bounded.

It operates within limits.

It is governed by principles that cannot be suspended simply because victory is at stake.

The enemy combatant may be fought.

The enemy army may be defeated.

The enemy’s military capacity may be destroyed.

But the enemy’s grandmother may not be killed.

The enemy’s children may not be slaughtered.

The enemy’s crops may not be burned.

The enemy’s water may not be poisoned.

The enemy’s land may not be rendered uninhabitable.

Why?

Because these people, these trees, these wells — they are not the enemy.

They are not the ones who declared the war, planned the aggression, led the armies.

They are, at worst, bystanders.

At best, they are victims — of their own rulers’ decisions, caught in a conflict they did not choose.

And Islam does not permit punishing the innocent for the crimes of the guilty.

The Argument from Lesser to Greater

Now we must apply reason to what we have established.

But we must be precise about what kind of reasoning we are employing.

In Imami jurisprudence, the tradition has rightly rejected qiyas (analogical reasoning) — the extension of rulings through inferred causes (‘illa) that the jurist estimates but cannot verify.

This rejection protects the Shariah from human conjecture masquerading as divine law.

But rejecting qiyas does not mean rejecting reason itself.

The Hawza recognises a category called al-mustaqillat al-’aqliyya — independent rational judgments.

These are moral conclusions that the intellect can reach on its own, without first borrowing a premise from revealed law.

The classic example is the rational recognition that justice is good and injustice is evil — husn al-’adl wa qubh al-dhulm.

This is not something we know because the Quran tells us (though the Quran confirms it).

It is something sound reason recognises independently.

Any intellect, reflecting honestly, knows that to harm the innocent is wrong, that to break a trust is evil, that to punish without cause is unjust.

These independent rational judgments connect to Shariah through the principle of mulazama — correlation.

If reason reaches a conclusion with certainty (qat’), it is inconceivable that the Shariah would contradict it.

God is wise and just; He does not command what sound reason recognises as evil, nor forbid what sound reason recognises as good.

This is the methodology we now apply.

The Prophet, peace be upon him and his family, forbade specific actions: killing the elderly, killing children, killing women, burning trees, destroying crops, poisoning wells.

Why are these forbidden?

Not because of some hidden cause we must guess at.

The reason is manifest: these actions constitute dhulm — injustice.

They harm those who do not deserve harm.

They destroy what should be protected.

They violate the rights of the innocent.

Now consider a nuclear weapon.

Does it kill children?

It kills thousands of them — in an instant, without distinction, without the possibility of sparing even one.

Does it kill women?

It incinerates them alongside the soldiers, the grandmothers alongside the generals.

Does it destroy trees?

It turns entire forests to ash, leaves the land barren, renders the soil poisonous for generations.

Does it poison wells?

It does worse — it poisons the aquifers, the rivers, the rain itself with radioactive contamination that persists for decades.

The argument here is not:

“Poisoning a well is forbidden, and a nuclear weapon is similar to poisoning a well, therefore we analogise the ruling.”

That would be qiyas, and we reject it.

The argument is:

“The reason poisoning a well is forbidden is because it constitutes dhulm — indiscriminate harm to the innocent, destruction of what sustains life.

A nuclear weapon is dhulm — directly, manifestly, undeniably.

It does not resemble injustice; it is injustice, on a scale the Prophet could not have imagined but whose nature he perfectly identified.”

Sound reason (‘aql salim) recognises this independently.

Any intellect, reflecting honestly on what a nuclear weapon does, knows that this is dhulm.

This is not juristic estimation.

This is moral certainty.